The puzzlement of scientists perplexes me. I have known about the possibility of this phenomenon since about 2003.

Scientists puzzled by slowing of Atlantic conveyor belt, warn of abrupt climate change

Scientists

are increasingly warning of the potential that a shutdown, or even

significant slowdown, of the Atlantic conveyor belt could lead to

abrupt climate change, a shift in Earth’s climate that can occur

within as short a timeframe as a decade but persist for decades or

centuries.

Mike

Gaworecki

Mongabay,

27 May, 2016

Limited

ocean measurements have shown that "the Atlantic conveyor belt"

is far more capricious than models have previously suggested.

- From 2009 to 2010, the average strength of key ocean currents in the North Atlantic dropped by about 30 percent, causing warmer waters to remain in the tropics rather than being carried northward.

- “The consequences included an unusually harsh European winter, a strong Atlantic Basin hurricane season, and — because a strong AMOC keeps water away from land — an extreme sea level rise of nearly 13 centimeters along the North American coast north of New York City,” according to Eric Hand, author of a Science article published this month.

Scientists

in the Labrador Sea recently made the first retrieval of data from

one of 53 lines moored to the sea floor and studded with instruments

that have been monitoring the ocean’s circulatory system since

2014.

Held

taut by submerged buoys, these moorings are arrayed from Labrador to

Greenland and Scotland. In total, five research cruises are planned

for this spring and summer to fetch the data the moorings are busy

collecting.

The

instrument array, known as the Overturning in the Subpolar North

Atlantic Program (OSNAP), measures salinity, temperature, and current

velocity of the surrounding water, data that is vital to

understanding a set of powerful currents with far-reaching effects on

the global climate. These currents are known as the Atlantic

Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) — or, more popularly,

“the Atlantic conveyor belt” — and they have “mysteriously”

slowed down over the past decade, according to Eric Hand, author of

a Science article

published this month.

Scientists

are increasingly warning of the potential that a shutdown, or even

significant slowdown, of the Atlantic conveyor belt could lead to

abrupt climate change, a shift in Earth’s climate that can occur

within as short a timeframe as a decade but persist for decades or

centuries.

North

Atlantic waters, such as the Greenland, Irminger, and Labrador Seas,

are especially salty when compared with water in other parts of the

world’s oceans. When AMOC currents, like the Gulf Stream, bring

warmer waters from the south to the North Atlantic, the water cools

down, releases its heat to the atmosphere, becomes colder, and sinks,

since saltier water is denser than fresher water and cold water is

denser than warm water.

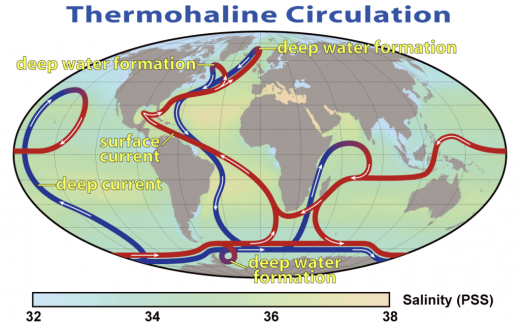

In

a process called “thermohaline circulation” (“thermos” is the

Greek word for heat, while “halos” is the word for salt), this

cold, salty water then slowly flows back down into the South Atlantic

and eventually makes its way throughout the world’s oceans. At the

same time, warm, salty tropical surface waters are drawn northward,

where they replace the sinking cold water.

This

map shows the pattern of thermohaline circulation also known as

“meridional overturning circulation”. This collection of currents

is responsible for the large-scale exchange of water masses in the

ocean, including providing oxygen to the deep ocean. The entire

circulation pattern takes ~2000 years. Image

viaclass="Apple-converted-space" Wikimedia

Commons.

In

other words, the dynamic at play in the North Atlantic seas are an

important driver of the ocean’s circulation system, which is why

the region was selected for the OSNAP instrument array. Two other

arrays that have been deployed in different waters have already

produced some strange results that scientists are eager to learn more

about.

“Models

suggest that climate change should weaken the AMOC as warmer Arctic

temperatures, combined with buoyant freshwater from Greenland’s

melting ice cap, impede the formation of deep currents,” Hand wrote

in the Science article. “But so far, limited ocean measurements

show the AMOC to be far more capricious than the models have been

able to capture.”

An

array deployed in 2004 between Florida and the Canary Islands, for

instance, showed “unexpectedly wild swings” in the strength of

the AMOC currents from month to month, Hand reported. From 2009 to

2010, the average strength of the AMOC dropped by about 30 percent,

causing warmer waters to remain in the tropics rather than being

carried northward.

“The

consequences included an unusually harsh European winter, a strong

Atlantic Basin hurricane season, and — because a strong AMOC keeps

water away from land — an extreme sea level rise of nearly 13

centimeters along the North American coast north of New York City,”

Hand said.

Over

its first decade of operation, the Florida-to-Canary Islands

subtropical array recorded a 25 percent decline in the AMOC’s

average strength, which is an order of magnitude more than models

suggested could occur due to the effects of climate change.

Meric

Srokosz, an oceanographer at the UK’s University of Southampton and

the science coordinator for the U.K.-funded portion of the array,

told Hand that scientists suspect some natural variation is to blame

in the dropoff of the AMOC’s strength, including the 60- to 70-year

cycle of varying sea temperatures called the Atlantic Multidecadal

Oscillation. Initial analysis of the latest, unpublished data from

the array shows the AMOC’s average strength has leveled out, but is

still well below where it started in 2004.

“It

will take another decade of measurements to separate the climate

change effect from natural variability,” Hand wrote.

Threat of abrupt climate change

Models

have suggested that there is a threshold below which the AMOC could

suddenly shut down altogether — “the doomsday scenario of a

frozen Europe exploited in the 2004 disaster movie The

Day After Tomorrow,”

as Hand put it. “Many climate models suggest that the AMOC should

be stable over the long term in a warming world, but plenty of

evidence from the recent geological past confirms that the conveyor

belt can slow down significantly.”

As

far back as 2003, Robert Gagosian, who was then the President and

Director of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in Woods

Hole, Massachusetts (he’s now President Emeritus), warned that we

ignore the threat of abrupt climate change induced by a slowing or

shutdown of the AMOC at our own peril.

“[T]he

debate on global change has largely failed to factor in the

inherently chaotic, sensitively balanced, and threshold-laden nature

of Earth’s climate system and the increased likelihood of abrupt

climate change,” he wrote in a post

on the WHOI website.

Speculation

about the future impacts of climate change focus on forecasts by the

UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which projects

gradual global warming of 1.4 to 5.8-degree Celsius over the next

century, Gagosian wrote at the time. That doesn’t appear to have

significantly changed, as the Paris Climate Agreement signed in

December of last year commits signatory countries to limiting warming

to 2 degrees Celsius, with an aspirational goal of limiting it to 1.5

degrees Celsius — and there’s little to no mention of how the

world will fend off the possibility of abrupt climate change.

But

we’d be wise to include in our forecasts the potential for

relatively sudden, possibly localized climate change induced by

thermohaline shutdown, Gagosian argued. “Such a change could cool

down selective areas of the globe by 3° to 5° Celsius, while

simultaneously causing drought in many parts of the world.”

These

abrupt changes could occur even while other regions of the globe

continue to warm more gradually, Gagosian said, making it “critical

to consider the economic and political ramifications of this

geographically selective climate change. Specifically, the region

most affected by a shutdown — the countries bordering the North

Atlantic — is also one of the world’s most developed.”

CITATION

- Gagosian, R. B. (2003). Abrupt climate change: should we be worried. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

- Hand, E. (2016). New scrutiny for a slowing Atlantic conveyor. Science, 352(6287), 751-752. doi:10.1126/science.352.6287.751

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.