Two big explanations - geopolitics and the world economy (Peak Oil). Are they mutually exclusive?

WTI

Hits $52 Handle As US Rig Count Tumbles To 8-Month Lows

29

December, 2014

Just

as T.

Boone Pickens warned "watch the rig counts" last week,

so the Baker Hughes rig countjust collapsed for the 3rd week in a row

to 8-month lows. This is the fastest 3-week drop since mid-2009.

Crude prices were already weak but the news has flushed WTI to a $52

handle (not seen in the front-month contract since May 2009)

Rig

count is tumbling...

Some

context for the surge in US rig count...

And

while the drop in Canadian rig count sounds impressive - it's the

worst since 2009 - it's much more seasonal

WTI

Hits A $52 handle!!

And

then there's this...

Charts:

bloomberg

"NATO

and the United States should change their policy because the time

when they dictate their conditions to the world has passed,"

Ahmadinejad said in a speech in Dushanbe, capital of the Central

Asian republic of Tajikistan

Did

the U.S. and the Saudis Conspire to Push Down Oil Prices?

Irreversible

Decline?

29

December, 2014

by

MIKE WHITNEY

“Saudi oil policy… has been subject to a great deal of wild and inaccurate conjecture in recent weeks. We do not seek to politicize oil… For us it’s a question of supply and demand, it’s purely business.”

– Ali al Naimi, Saudi Oil Minister

“There is no conspiracy, there is no targeting of anyone. This is a market and it goes up and down.”

– Suhail Bin Mohammed al-Mazroui, United Arab Emirates’ petroleum minister

“We all see the lowering of oil prices. There’s lots of talk about what’s causing it. Could it be an agreement between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia to punish Iran and affect the economies of Russia and Venezuela? It could.”

– Russian President Vladimir Putin

Are

falling oil prices part of a US-Saudi plan to inflict economic damage

on Russia, Iran and Venezuela?

Venezuelan

President Nicolas Maduro seems to think so. In a recent interview

that appeared in Reuters, Maduro said he thought the United States

and Saudi Arabia wanted to drive down oil prices “to harm Russia.”

Bolivian

President Evo Morales agrees with Maduro and told journalists at RT

that: “The reduction in oil prices was provoked by the US as an

attack on the economies of Venezuela and Russia. In the face of such

economic and political attacks, the nations must be united.”

Iranian

President Hassan Rouhani said the same thing,with a slightly

different twist: “The main reason for (the oil price plunge) is a

political conspiracy by certain countries against the interests of

the region and the Islamic world … Iran and people of the

region will not forget such … treachery against the interests of

the Muslim world.”

US-Saudi

“treachery”? Is that what’s really driving down oil prices?

Not

according to Saudi Arabia’s Petroleum Minister Ali al-Naimi.

Al-Naimi has repeatedly denied claims that the kingdom is involved in

a conspiracy. He says the tumbling prices are the result of “A lack

of cooperation by non-OPEC production nations, along with the spread

of misinformation and speculator’s greed.” In other words,

everyone else is to blame except the country that has historically

kept prices high by controlling output. That’s a bit of a stretch,

don’t you think? Especially since–according to the Financial

Times — OPEC’s de facto leader has abandoned the cartel’s

“traditional strategy” and announced that it won’t cut

production even if prices drop to $20 per barrel.

Why?

Why would the Saudis suddenly abandon a strategy that allowed them to

rake in twice as much dough as they are today? Don’t they like

money anymore?

And

why would al-Naimi be so eager to crash prices, send Middle East

stock markets into freefall, increase the kingdom’s budget deficits

to a record-high 5 percent of GDP, and create widespread financial

instability? Is grabbing “market share” really that important or

is there something else going on here below the surface?

The

Guardian’s Larry Elliot thinks the US and Saudi Arabia are engaged

a conspiracy to push down oil prices. He points to a September

meeting between John Kerry and Saudi King Abdullah where a deal was

made to boost production in order to hurt Iran and Russia. Here’s a

clip from the article titled “Stakes are high as US plays the oil

card against Iran and Russia”:

“…with the help of its Saudi ally, Washington is trying to drive down the oil price by flooding an already weak market with crude. As the Russians and the Iranians are heavily dependent on oil exports, the assumption is that they will become easier to deal with…

John Kerry, the US secretary of state, allegedly struck a deal with King Abdullah in September under which the Saudis would sell crude at below the prevailing market price. That would help explain why the price has been falling at a time when, given the turmoil in Iraq and Syria caused by Islamic State, it would normally have been rising.

The Saudis did something similar in the mid-1980s. Then, the geopolitical motivation for a move that sent the oil price to below $10 a barrel was to destabilize Saddam Hussein’s regime. This time, according to Middle East specialists, the Saudis want to put pressure on Iran and to force Moscow to weaken its support for the Assad regime in Syria… (Stakes are high as US plays the oil card against Iran and Russia, Guardian)

That’s

the gist of Elliot’s theory, but is he right?

Vladimir

Putin isn’t so sure. Unlike Morales, Maduro and Rouhani, the

Russian president has been reluctant to blame falling prices on

US-Saudi collusion. In an article in Itar-Tass, Putin opined:

“There’s a lot of talk around” in what concerns the causes for the slide of oil prices, he said at a major annual news conference. “Some people say there is conspiracy between Saudi Arabia and the US in order to punish Iran or to depress the Russian economy or to exert impact on Venezuela.”

“It might be really so or might be different, or there might be the struggle of traditional producers of crude oil and shale oil,” Putin said. “Given the current situation on the market the production of shale oil and gas has practically reached the level of zero operating costs.” (Putin says oil market price conspiracy between Saudi Arabia and US not ruled out, Itar-Tass)

As

always, Putin takes the most moderate position, that is, that

Washington and the Saudis may be in cahoots, but that droopy prices

might simply be a sign of over-supply and weakening demand. In other

words, there could be a plot, but then again, maybe not. Putin is a

man who avoids passing judgment without sufficient evidence.

The

same can’t be said of the Washington Post. In a recent article, WP

journalist Chris Mooney dismisses anyone who thinks oil prices are

the result of US-Saudi collaboration as “kooky conspiracy

theorists”. According to Mooney:

“The reasons for the sudden (price) swing are not particularly glamorous: They involve factors like supply and demand, oil companies having invested heavily in exploration several years ago to produce a glut of oil that has now hit the market — and then, perhaps, the “lack of cohesion” among the diverse members of OPEC.” (Why there are so many kooky conspiracy theories about oil, Washington Post)

Oddly

enough, Mooney disproves his own theory a few paragraphs later in the

same piece when he says:

“Oil producers really do coordinate. And then, there’s OPEC, which is widely referred to in the press as a “cartel,” and which states up front that its mission is to “coordinate and unify the petroleum policies” of its 12 member countries…. Again, there’s that veneer of plausibility to the idea of some grand oil related strategy.” (WP)

Let

me get this straight: One the one hand Mooney agrees that OPEC is a

cartel that “coordinates and unify the petroleum policies”, then

on the other, he says that market fundamentals are at work. Can you

see the disconnect? Cartels obstruct normal supply-demand dynamics by

fixing prices, which Mooney seems to breezily ignore.

Also,

he scoffs at the idea of “some grand oil related strategy” as if

these cartel nations were philanthropic organizations operating in

the service of humanity. Right. Someone needs to clue Mooney in on

the fact that OPEC is not the Peace Corps. They are monopolizing

amalgam of cutthroat extortionists whose only interest is maximizing

profits while increasing their own political power. Surely, we can

all agree on that fact.

What’s

really wrong with Mooney’s article, is that he misses the point

entirely. The debate is NOT between so-called “conspiracy

theorists” and those who think market forces alone explain the

falling prices. It’s between the people who think that the Saudis

decision to flood the market is driven by politics rather than a

desire to grab “market share.” That’s where people disagree. No

denies that there’s manipulation; they merely disagree about the

motive. This glaring fact seems to escape Mooney who is on a mission

to discredit conspiracy theorists at all cost. Here’s more:

(There’s) “a long tradition of conspiracy theorists who have surmised that the world’s great oil powers — whether countries or mega-corporations — are secretly pulling strings to shape world events.”…

“A lot of conspiracy theories take as their premise that there’s a small group of people who are plotting to control something, to control the government, the banking system, or the main energy source, and they are doing this to the disadvantage of everybody else,” says University of California-Davis historian Kathy Olmsted, author of “Real Enemies: Conspiracy Theories and American Democracy, World War I to 9/11″. (Washington Post)

Got

that? Now find me one person who doesn’t think the world is run by

a small group of rich, powerful people who operate in their own best

interests? Here’s more from the same article:

(Oil) “It’s the perfect lever for shifting world events. If you were a mad secret society with world-dominating aspirations and lots of power, how would you tweak the world to create cascading outcomes that could topple governments and enrich some at the expense of others? It’s hard to see a better lever than the price of oil, given its integral role in the world economy.” (WP)

“A

mad secret society”? Has Mooney noticed that — in the last decade

and a half — the US has only invaded nations that have huge natural

resources (mainly oil and natural gas) or the geography for critical

pipeline routes? There’s nothing particularly secret about it, is

there?

The

United States is not a “mad secret society with world-dominating

aspirations”. It’s a empire with blatantly obvious

“world-dominating aspirations” run by political puppets who do

the work of wealthy elites and corporations. Any sentient being who’s

bright enough to browse the daily headlines can figure that one out.

Mooney’s

grand finale:

“So in sum, with a surprising and dramatic event like this year’s oil price decline, it would be shocking if it did not generate conspiracy theories. Humans believe them all too easily. And they’re a lot more colorful than a more technical (and accurate) story about supply and demand.” (WP)

Ah,

yes. Now I see. Those darn “humans”. They’re so weak-minded

they’ll believe anything you tell them, which is why they need

someone as smart as Mooney tell them how the world really work.

Have

you ever read such nonsense in your life? On top of that, he gets the

whole story wrong. This isn’t about market fundamentals. It’s

about manipulation. Are the Saudis manipulating supply to grab market

share or for political reasons? THAT’S THE QUESTION. The fact that

they ARE manipulating supply is not challenged by anyone including

the uber-conservative Financial Times that deliberately pointed out

that the Saudis had abandoned their traditional role of cutting

supply to support prices. That’s what a “swing state” does; it

manipulates supply keep prices higher than they would be if market

forces were allowed to operate unimpeded.

So

what is the motive driving the policy; that’s what we want to know?

Certainly

there’s a strong case to be made for market share. No one denies

that. If the Saudis keep prices at rock bottom for a prolonged period

of time, then a high percentage of the producers (that can’t

survive at prices below $70 per barrel) will default leaving OPEC

with greater market share and more control over pricing.

So

market share is certainly a factor. But is it the only factor?

Is

it so far fetched to think that the United States–which in the last

year has imposed harsh economic sanctions on Russia, made every

effort to sabotage the South Stream pipeline, and toppled the

government in Kiev so it could control the flow of Russian gas to

countries in the EU–would coerce the Saudis into flooding the

market with oil in order to decimate the Russian economy, savage the

ruble, and create favorable conditions for regime change in Moscow?

Is that so hard to believe?

Apparently

New York Times columnist Thomas Freidman doesn’t think so. Here’s

how he summed it up in a piece last month: “Is it just my

imagination or is there a global oil war underway pitting the United

States and Saudi Arabia on one side against Russia and Iran on the

other?”

It

sounds like Freidman has joined the conspiracy throng, doesn’t it?

And he’s not alone either. This is from Alex Lantier at the World

Socialist Web Site:

“While there are a host of global economic factors underlying the fall in oil prices, it is unquestionable that a major role in the commodity’s staggering plunge is Washington’s collaboration with OPEC and the Saudi monarchs in Riyadh to boost production and increase the glut on world oil markets.

As Obama traveled to Saudi Arabia after the outbreak of the Ukraine crisis last March, the Guardian wrote, “Angered by the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, the Saudis turned on the oil taps, driving down the global price of crude until it reached $20 a barrel (in today’s prices) in the mid-1980s… [Today] the Saudis might be up for such a move—which would also boost global growth—in order to punish Putin over his support for the Assad regime in Syria. Has Washington floated this idea with Riyadh? It would be a surprise if it hasn’t.” (Alex Lantier,Imperialism and the ruble crisis, World Socialist Web Site)

And

here’s an intriguing clip from an article at Reuters that suggests

the Obama administration is behind the present Saudi policy:

“U.S.

Secretary of State John Kerry sidestepped the issue (of a US-Saudi

plot) after a trip to Saudi Arabia in September. Asked if past

discussions with Riyadh had touched on Russia’s need for oil above

$100 to balance its budget, he smiled and said: “They (Saudis) are

very, very well aware of their ability to have an impact on global

oil prices.” (Saudi

oil policy uncertainty unleashes the conspiracy theorists,

Reuters)

Wink, win.

Of

course, they’re in bed together. Saudi Arabia is a US client. It’s

not autonomous or sovereign in any meaningful way. It’s a US

protectorate, a satellite, a colony. They do what they’re told.

Period. True, the relationship is complex, but let’s not be

ridiculous. The Saudis are not calling the shots. The idea is absurd.

Do you really think that Washington would let Riyadh fiddle prices in

a way that destroyed critical US domestic energy industries, ravaged

the junk bond market, and generated widespread financial instability

without uttering a peep of protest on the matter?

Dream

on! If the US was unhappy with the Saudis, we’d all know about it

in short-order because it would be raining Daisy Cutters from the

Persian Gulf to the Red Sea, which is the way that Washington

normally expresses its displeasure on such matters. The fact that

Obama has not even alluded to the shocking plunge in prices just

proves that the policy coincides with Washington’s broader

geopolitical strategy.

And

let’s not forget that the Saudis have used oil as a political

weapon before, many times before. Indeed, wreaking havoc is nothing

new for our good buddies the Saudis. Check this out from Oil Price

website:

“In 1973, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat convinced Saudi King Faisal to cut production and raise prices, then to go as far as embargoing oil exports, all with the goal of punishing the United States for supporting Israel against the Arab states. It worked. The “oil price shock” quadrupled prices.

It happened again in 1986, when Saudi Arabia-led OPEC allowed prices to drop precipitously, and then in 1990, when the Saudis sent prices plummeting as a way of taking out Russia, which was seen as a threat to their oil supremacy. In 1998, they succeeded. When the oil price was halved from $25 to $12, Russia defaulted on its debt.

The Saudis and other OPEC members have, of course, used the oil price for the obverse effect, that is, suppressing production to keep prices artificially high and member states swimming in “petrodollars”. In 2008, oil peaked at $147 a barrel.” (Did The Saudis And The US Collude In Dropping Oil Prices?, Oil Price)

1973,

1986, 1990, 1998 and 2008.

So,

according to the author, the Saudis have manipulated oil prices at

least five times in the past to achieve their foreign policy

objectives. But, if that’s the case, then why does the media

ridicule people who think the Saudis might be engaged in a similar

strategy today?

Could

it be that the media is trying to shape public opinion on the issue

and, by doing so, actually contribute to the plunge in oil prices?

Bingo.

Alert readers have probably noticed that the oil story has been

splashed across the headlines for weeks even though the basic facts

have not changed in the least. It’s all a rehash of the same

tedious story reprinted over and over again.

But, why? Why does the

public need to have the same “Saudis refuse to cut production”

story driven into their consciousness day after day like they’re

part of some great collective brainwashing experiment? Could it be

that every time the message is repeated, oil sells off, and prices go

down? Is that it?

Precisely.

For example, last week a refinery was attacked in Libya which pushed

oil prices up almost immediately. Just hours later, however, another

“Saudis refuse to cut production” story conveniently popped up in

all the major US media which pushed prices in the direction the USG

wants them to go, er, I mean, back down again.

This

is how the media helps to reinforce government policy, by crafting a

message that helps to push down prices and, thus, hurt “evil”

Putin. (This is called “jawboning”) Keep in mind, that OPEC

doesn’t meet again until June, 2015, so there’s nothing new to

report on production levels. But that doesn’t mean we’re not

going to get regular updates on the “Saudis refuse to cut

production” story.

Oh, no. The media is going to keep beating that

drum until Putin cries “Uncle” and submits to US directives.

Either that, or the bond market is going to blow up and take the

whole damn global financial system along with it. One way or another,

something’s got to give.

Bottom

line: Falling oil prices and the plunging ruble are not some kind of

free market accident brought on by oversupply and weak demand. That’s

baloney.

They’re part of a broader geopolitical strategy to

strangle the Russian economy, topple Putin, and establish US hegemony

across the Asian landmass. It’s all part of Washington’s plan to

maintain its top-spot as the world’s only superpower even though

its economy is in irreversible decline.

MIKE

WHITNEY lives

in Washington state. He is a contributor to Hopeless:

Barack Obama and the Politics of Illusion (AK

Press). Hopeless is also available in a Kindle

edition. He

can be reached at fergiewhitney@msn.com.

Analyzing oil prices

How

increased inefficiency explains falling oil prices

Gail

Tverberg

29

December, 2014

Since

about 2001, several sectors of the economy have become increasingly

inefficient, in the sense that it takes more resources to produce a

given output, such as 1000 barrels of oil. I believe that this

growing inefficiency explains both slowing world economic growth and

the sharp recent drop in prices of many commodities, including oil.

The

mechanism at work is what I would call the crowding

out effect.

As more resources are required for the increasingly inefficient

sectors of the economy, fewer resources are available to the rest of

the economy. As a result, wages stagnate or decline. Central banks

find it necessary lower interest rates, to keep the economy going.

Unfortunately,

with stagnant or lower wages, consumers find that goods from the

increasingly inefficiently sectors are increasingly unaffordable,

especially if prices rise to cover the resource requirements of these

inefficient sectors. For most periods in the past, commodities

prices have stayed close to the cost of production (at least for the

“marginal producer”). What we seem to be seeing recently is a

drop in price to what

consumers can afford for

some of these increasingly unaffordable sectors. Unless this

situation can be turned around quickly, the whole system risks

collapse.

Increasingly

Inefficient Sectors of the Economy

We

can think of several increasingly inefficient sectors of the economy:

Oil. The

problem with oil is that much of the easy (and thus, cheap) to

extract oil is gone. There seems to be a great deal of

expensive-to-extract oil available. Some of it is deep under the sea,

even under salt layers. Some of it is very heavy and needs to be

“steamed” out. Some of it requires “fracking.” The extra

extraction steps require the use of more human labor and more

physical resources (oil and gas, metal pipes, fresh water), but

output rises by very little. Liquid extenders to oil, such as

biofuels and coal-to-liquid operations, also tend to be heavy

resource users, further exacerbating the problem of the rising cost

of production for liquid fuels.

I

have described the problem behind rising costs as increasing

inefficiency of production.

The technical name for our problem is diminishing

returns. This

situation occurs when increased investment offers ever-smaller

returns. Diminishing returns tends to occur to some extent whenever

resources of any kind are extracted from the ground. If the extent of

diminishing returns is small enough, total costs can be kept flat

with technological advances. Our problem now is that diminishing

returns have grown to such an extent that technological advances are

no longer keeping pace. As a result, the cost of producing many types

of goods and services is growing faster than wages.

Fresh

Water. This

is another increasingly inefficient sector of the economy, in terms

of the amount of fresh water that can be produced with a given amount

of resource investment. In some places deeper wells are needed; in

others, desalination plants. Water from deeper wells may need

additional treatment to remove the harmful minerals and radiation

found in water from deeper wells.

As

a result of the extra investment required, the price of fresh water

is rising in many parts of the world. The higher cost is often

justified as necessary to encourage conservation of a scarce

resource. But from the point of view of the buyer, what is happening

is an increasing price for the same product, or diminishing returns.

Grid

Electricity. The

price of grid electricity has been rising faster than inflation in

many parts of the world for a variety of reasons. If nuclear plants

are planned, they are being made in ways that are hopefully safer,

but are more expensive. Adding solar PV and offshore wind is

expensive, especially when grid changes to accommodate them are

considered as well. Functioning plants of various kinds (coal,

nuclear) are being replaced with other generation because of

pollution problems (CO2) or feared pollution problems

(radiation). The cost of producing electricity then rises

because the cost of electricity from a fully depreciated plant of any

kind is extremely low. Building any kind of new facility, no matter

how theoretically efficient over, say, the next 40 years, requires

physical resources and people’s time, in the current time period.

As

these changes are made, the amount of grid electricity output does

not rise very much compared to the resources and human labor required

in the current period. The user experiences a higher cost for the

same product. From the perspective of the user’s pocketbook, the

result looks like diminishing returns.

Metals

and Other Minerals. In

the same manner as oil, we extract the easiest (and cheapest) to

extract minerals first. These minerals include metals and other

substances such as uranium, lithium, and rare earth minerals. Part of

the problem is that ores of lower concentration must be used, leading

to a need to move larger amounts of extraneous material that later

must be disposed of. These ores may be found deeper in the ground or

in more remote locations, adding to extraction costs. Furthermore,

oil is generally used in the extraction of these minerals. As the

cost of oil cost rises, this adds to the cost of mineral extraction,

making minerals increasingly unaffordable.

Advanced

Education of Would-Be Workers. If

20% of the work force needs college educations, it makes sense to

provide 20% of young people workers with college educations. If the

percentage of workers requiring college educations rises to 30%, it

makes sense to provide 30% of young people with college educations.

Small percentages of more advanced degree recipients are needed as

well.

Instead

of following a common sense approach of educating only the number of

workers who need a given amount of education with that amount of

education, in the United States we have gotten onto a treadmill of

encouraging increasing numbers of young people to pursue bachelors,

masters, and Ph.D. degrees. To make matters worse, universities have

established requirements that faculty do more research and less

teaching, whether or not research in a particular field can be

expected to benefit the economy to any significant extent. To

accommodate this research-intensive approach, a layer of deans is

added to work on obtaining funding for research. In addition,

students are often provided more comfortable dorms with private rooms

and private baths, adding costs to obtaining advanced education but

not really enhancing future job prospects.

All

of this produces an incredibly expensive higher education system,

with costs way out of proportion to the increased wages a student can

expect to earn from attending the university. Students are expected

to pay for much of the cost of this system through debt to be paid

back after graduation (or after dropping out). In some ways, the

system might be viewed as an extremely expensive system of sorting

out would-be job applicants, with widget makers with a college degree

or master’s degree viewed more favorably than ones without, even if

there is little use for an advanced degree in that particular job.

US

Medical System. The

US Medical system is particularly affected by the trend toward more

advanced degrees. This approach results in a system where patients

need to visit a variety of specialists to handle fairly common

ailments, such as a broken arm or dementia in old age. To compensate

for the high cost of their advanced education, specialists charge

high fees. Hospitals have a large number of testing instruments at

their disposal and use them whenever there is even slight

justification.

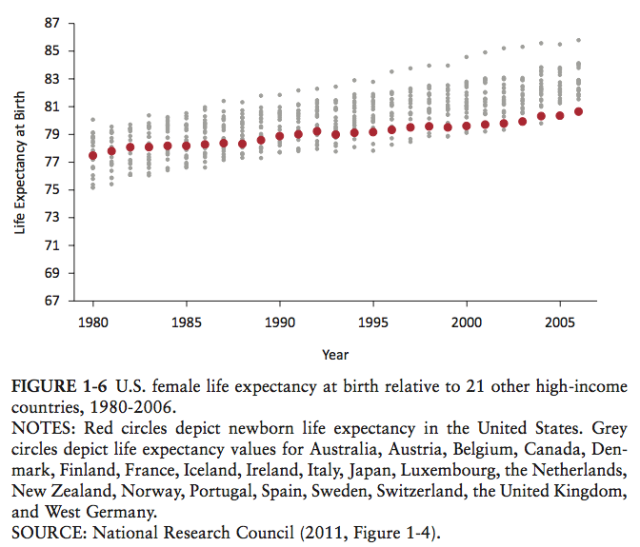

Health

outcomes in the US are remarkably bad compared to other developed

countries, based on a study by the US Institute of Medicine

called U.S.

Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health.

According

to this study, the US is falling farther and farther behind other

developed countries in terms of health outcomes and life expectancy,

despite healthcare

spending that is more than twice as expensive as that of some other

developed countries.

The

higher cost is not entirely the fault of the healthcare system. The

food production system provides food that is increasingly processed

(so is convenient), but is not well adapted to our bodily needs. Food

portions tend to be oversized, raising profits for fast food

companies, but adversely affecting health of consumers.

Transportation is set up in ways that deprive us of the exercise we

need. Also, part of the reason for the adverse health outcomes is the

fact that not all people are covered by health coverage, even with

the recent addition of Obamacare.

Regardless

of whose “fault” the problem is, the healthcare sector is

becoming increasingly inefficient. In some sense, we are reaching

diminishing returns here as well.

Effects

of Inefficient Sectors on Business Operations

Businesses

have a number of costs of operation. Unless wages are rising, they

can’t easily raise prices without losing customers. So if costs

rise in one area of their operations, they tend to try to cut costs

in other areas of operations to offset this rise. This is thecrowding

out principle

at work.

Among

the sectors described above as having increasingly inefficient

operations, the ones that directly affect businesses are

- Oil

- Fresh water

- Electricity

- Metals and other minerals

- Healthcare

Areas

where costs can be cut to make up for rising costs in the above areas

include:

Lower

interest rates.

If interest rates are low, this reduces expenses for businesses. It

also makes customers more able to tolerate higher costs of say,

automobiles and houses and education, because the “monthly payment”

can still appear reasonable, even if total cost rises. Lower interest

rates help reduce needed government taxes as well, further helping

both businesses and consumers. Because of these multiple favorable

effects, it is not surprising that central banks have been lowering

interest rates in recent years.

Reduced

wages for workers. Wages

often constitute a major share of a business’s costs. If the cost

of oil or electricity or health insurance rises, a common work-around

seems to be to transfer jobs to parts of the world where wage costs

are lower. If energy costs are also lower in the alternative part of

the world, this increases the attractiveness of moving jobs. Another

work-around is computerization of job functions, using computers to

replace jobs formerly done by workers. In fact, simply the

possibility of sending work elsewhere or of computerization tends to

hold wages down.

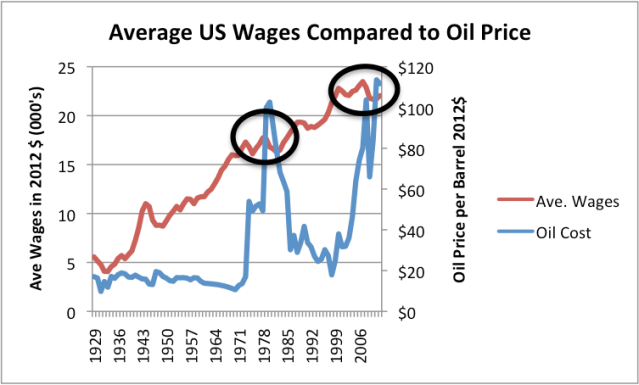

I

have shown that, in fact, US wages tend to stagnate when oil prices

are above $40 or $50 per barrel. This result is as we would expect,

if high oil prices tend to crowd out wages.

Figure

2. Average wages in 2012$ compared to Brent oil price, also in

2012$. Average wages are total wages based on BEA data adjusted by

the CPI-Urban, divided total population. Thus, they reflect changes

in the proportion of population employed as well as wage levels.

Transfer

of more health care costs to workers. Businesses

can cut their costs by moving part of healthcare costs to workers,

either through higher deductibles or through higher monthly payments

for coverage. This approach has a similar effect as a wage cut.

Lower

taxes on businesses. Government

provided services can be paid for either by taxes on businesses or by

taxes on workers. Many of these services benefit both businesses and

workers, so the split as to how these taxes should be collected is

not obvious. Businesses, especially international businesses, have

the option of moving to locations with more favorable tax laws.

The trend

in recent years has been toward lower taxes on business revenue,

shifting a greater share of taxes to wage earners. Higher taxes on

wage earners also acts very similarly to a reduction in wages.

More

debt. This

is different kind of work-around for higher costs. Instead of reduced

expenses, it provides increased revenue for businesses. This revenue

is borrowed from a future period, with the promise that it will be

repaid with interest. The use of more debt is especially prevalent in

the sectors of the economy that are increasingly inefficient. For

example, adding new desalination plants is enabled by more debt.

Adding more renewable energy and more nuclear plants is enabled by

more debt. The increasing the cost of higher education is enabled by

more debt. Adding such debt is enabled by the lower interest rates

mentioned above.

Effect

on Wage Earners of Economy’s Growing Inefficiency

Wage

earners find themselves caught in a world with growing inefficiency

in many sectors. Their wages are not rising very much, except in a

few occupations requiring very high education.

Wage

earners find themselves increasingly squeezed. They take out big

student loans, only to discover that they really cannot pay them back

without deferring buying a home and having a family. Thus the housing

industry stagnates. The need for new home furnishing drops as well.

Births drop below the “replacement rate.” Young people

forego buying cars, because they don’t have good-paying jobs. In

fact, many are trying to go to school and work at a low-paid

part-time job to support themselves. These jobs do not pay high

enough wages to afford a car, so oil use tends to decline.

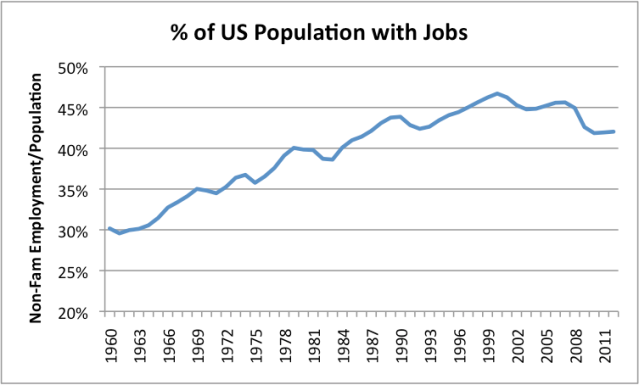

With

wage levels low, women find that it does not make financial sense to

join the paid work force if they have children, because the cost of

transportation and child care is too high, relative to the wages of,

say, a teacher–a job that requires a college education. The

situation is similar if an elderly relative or handicapped adult

child needs care. As a result, work force participation levels drop.

This change started to occur about 2001 in the US.

Figure

3. US Number Employed / Population, where US Number Employed is

Total Non-Farm Workers from Current Employment Statistics of the

Bureau of Labor Statistics and Population is US Resident Population

from the US Census. (This includes children and others not usually

in the labor force.) 2012 is a partial year estimate.

The

Effect of Diminishing Returns (and Crowding Out) on Debt

As

the economy becomes less efficient, there are clearly multiple

impacts on debt:

- Both businesses and individuals need more debt, because they become less able to purchase the increasingly costly devices they are being asked to purchase (new cars, new factories, new oil extraction facilities requiring significant investment)

- For businesses, the returns on this debt are falling in terms of output measured in units such as barrels of oil or kilowatt hours of electricity; it is only if ever-higher prices for the output can be charged that the debt can be repaid.

- For citizens, wages are becoming less able to cover the cost of needed goods. This both increases the need for debt, and makes debt increasingly difficult to repay.

- Diminishing returns leads to lower economic growth. It is only if interest rates can be kept very low that debt can possibly be repaid. At some point, required interest rates turn negative.

As

long as an economy is expanding, it makes financial sense to “borrow

from the future”.

It

even makes sense to pay back the debt with interest, because with the

growth, there is a reasonable possibility that even with interest,

the amount available in the future period will still be increasing,

even net of a debt payment.

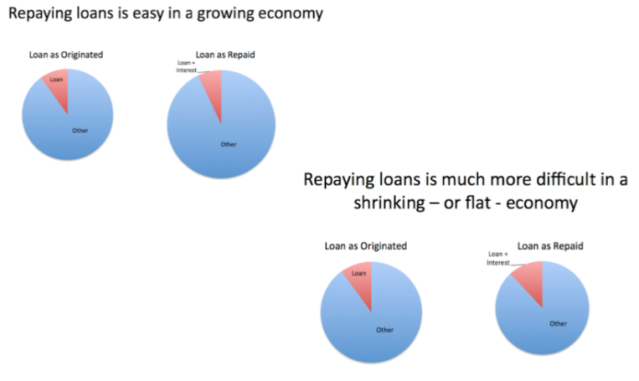

Figure

5. Repaying loans is easy in a growing economy, but much more

difficult in a shrinking economy.

If

we think of interest being paid to what is sometimes called

the rentier class

(that is banks, insurance companies, pension plans, and rich

individuals), then it is the rentier class that is being squeezed by

the increased inefficiency that is leading to slow economic growth.

In some cases, interest rates are even turning negative, reflecting

the poor prospects for the economy. Of course, with negative interest

rates, we cannot expect a whole lot of investment–people would

rather keep money under their beds than invest it at a negative rate

of return.

Crowding

Out of Oil Usage

World

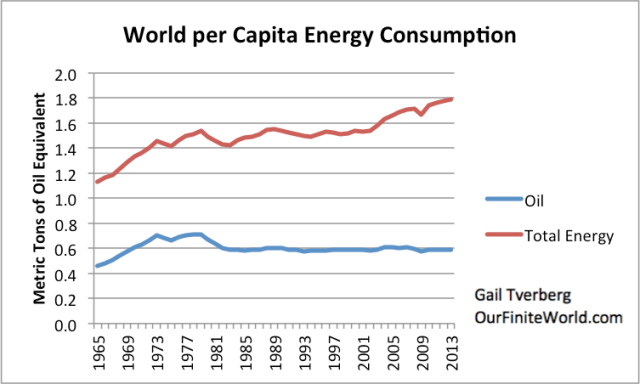

oil consumption has been essentially flat since 1983 on a per-capita

basis. Most people have not noticed this change, because world per

capita energy consumption has been rising for many years, helping to

raise standards of living around the world.1

Figure

6. World per capita oil and total energy consumption, based on BP

Statistical Review of World Energy 2014 data.

The

issue we are concerned about in this post is the squeezing out

phenomenon, as it relates to oil. As we noted above, there are a

number of industries that are becoming less and less efficient,

including oil, electricity, metal and minerals, fresh water, higher

education, and the medical system. Because of this issue, these

sectors are using an increasing share of the world’s oil

supply, when direct and indirect usage are included.2

We

don’t know exactly how much oil is being devoted to the six

increasingly inefficient sectors described in this post, but we do

know that the oil consumption per capita devoted to uses other than

these six sectors must be falling, because the total is

flat. Examples of sectors being crowded out are restaurants,

hotels, news media, home building, computer manufacturing, vacation

travel, lawn care, and most of the general economy.

The

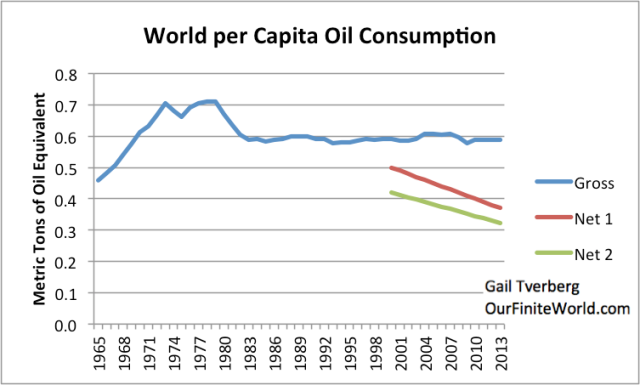

problem with increased inefficiency has been especially acute since

2001, as evidenced by falling employment ratios (Figure 3) and rising

oil and commodity prices since that date. In Figure 7, we show two

possible trajectories of oil available to the rest of society, net of

use by these increasingly inefficient sectors.

Figure

7. World per capita oil consumption based on BP Statistical Review

of World Energy oil data, and two possible trajectories of per

capita oil supply available to the rest of the economy, selected by

author.

It

is very difficult for the sectors that are getting crowded out by the

increasingly inefficient sectors to grow, despite growing energy

usage other than oil. Oil has many specialized uses. Even if total

energy use grows, it cannot make up for uses where oil is

specifically needed, such as operating a diesel truck or operating

road paving equipment. Thus costs to say, the newspaper industry, are

higher if oil prices are higher, but the disposable income citizens

have available to spend on newspapers is lower, resulting in the

crowding out phenomenon.

Conclusion

We

are dealing with a networked economy, which I have represented in the

past as this child’s toy:

Figure

7. Dome constructed using Leonardo

Sticks

All

parts of our economy are interconnected. If parts of the economy is

becoming increasingly inefficient, more than the cost of production

in these parts of the economy are affected; other parts of the

economy are affected as well, including wages, debt levels, and

interest rates.

Wages

are especially being crowded out, because the total amount of goods

and services available for purchase in the world economy is growing

more slowly. This is not intuitively obvious, unless a person stops

to realize that if the world economy is growing more slowly, or

actually shrinking, it is producing less. Each worker gets a share of

this shrinking output, so it is reasonable to expect

inflation-adjusted wages to be stagnating or declining, since a

stagnating or declining collection of goods and services is all a

person can expect.

At

some point, something has to “give”. One thing we have seen

recently is a sudden drop in oil prices that does not represent a

sudden drop in the cost of extraction. Instead, it reflects the fact

that current wages are not high enough to pay today’s high cost of

oil extraction. There is getting to be a difference between

- The full cost of oil extraction, including governmental services needed to keep the country’s economy functioning well enough for this extraction to continue, and

- The amount the economy can afford, considering both wages and the increase (or decrease) in debt for the economy.

This

situation is not simply affecting oil; it is also affecting other

commodity prices as well. Clearly we cannot continue

indefinitely on this trajectory. Something has to give. So far, what

we have seen is a drop in oil prices and other commodity prices to

levels that are likely to seriously disrupt production. How this will

all play out is worrisome, if a person understands the dynamics

behind what is happening.

Notes:

[1]

The mix of fuels has been changing, however, with coal use rising in

recent years (as we have shifted manufacturing to coal-producing

countries) while oil use per capita has remained nearly flat since

1983 (Figure 6). The big decrease in oil consumption per capita in

the late 1970s and early 1980s took place in response to the spike in

oil prices in the 1970s and early 1980s. Electricity generation

shifted from using oil to using coal or nuclear. Cars were made more

efficient. Once the “low hanging fruit” were picked in this

period, it has not been possible to reduce world per capita oil usage

(including substitutes like biofuels and natural gas liquids).

[2] The

oil usage I am counting is this analysis is both (a) direct usage by

the industry and (b) usage by employees and contractors working in

these industries. With a growing number of workers and high wages,

these workers are able to afford nice homes, big cars, and vacations

requiring air travel. Usage of oil by governments in oil exporting

countries should probably also be included as (c) in this list of

directly related types of usage, because this usage is necessary to

maintain order in these countries

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.