"Are

IPCC projected rates of sea level rise too

conservative? "You can bet

your bottom dollar on it.

Warm

Water Rising From

the Depths: Much of

Antarctica Now Under

Threat of

Melt

9

December, 2014

Antarctica.

A seemingly impregnable fortress of cold. Ice mountains rising 2,100

meters high. Circumpolar winds raging out from this mass of chill

frost walling the warm air out. And a curtain of sea ice insulating

the surface air and mainland ice sheets from an increasingly warm

world. A world that is now on track to experience one of its hottest

years on record.

Antarctica,

the coldest place on Earth, may well seem impregnable to this

warming. But like any other fortress, it has its vulnerable spots. In

this case, a weak underbelly. For in study after study, we keep

finding evidence that warm waters are rising up from the abyss

surrounding the chill and frozen continent. And the impact and risk

to Antarctica’s glacial ice mountains is significant and

growing.ent GDP by the end of 2014.

Getting

a hold on the budget deficit – both within the government and key

state-owned companies like Naftogaz – is a requirement IMF put

forward to allow further loans to Ukraine. It also demanded a hike in

utility prices, which the Yatsenyuk government is currently putting

into place. The measures are causing understandable irritation among

the Ukrainian population, who are not thrilled to see their bills

skyrocket amid an economic slowdown plaguing the country.

(Collapse of ice structure at the leading edge of the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf adjacent to a rapidly warming Weddell Sea during January of 2010. A new study has found warm water upwelling from the Circumpolar Deep Water is rapidly approaching this massive ice shelf. Loss of Filchner-Ronne and its inland buttressed glaciers would result in 10 feet of sea level rise. Image source: Commons.)

For

a study this week confirmed that Antarctica is now seeing a yearly

loss of ice equal to one half the volume of Mt Everest every single

year. A rate of loss triple that seen just ten years ago. An

acceleration that, should it continue, means a much more immediate

threat to coastal regions from sea level rise than current IPCC

projections now estimate.

Shoaling

of the Circumpolar Deep Water

The

source of this warm water comes from a deep-running current that

encircles all of Antarctica. Called the Circumpolar Deep Water, this

current runs along the outside margin of the continental shelf.

Lately, the current has been both warming and rising up the

boundaries of the continental zone. And this combined action is

rapidly bringing Antarctica’s great ice sheets under increasing

threat of more rapid melt.

According

to a

new study led by Sunke Schmidtko, this deep water current has

been warming at a rate of 0.1 degrees Celsius per decade since 1975.

Even before this period of more rapid deep water warming, the current

was already warmer than the continental shelf waters near

Antarctica’s great glaciers. With the added warming, the

Circumpolar Deep Water boasts temperatures in the range of 33 to 35

degrees Fahrenheit — enough heat to melt any glacier it contacts

quite rapidly.

Out

in the deep ocean waters beyond the continental shelf zone

surrounding Antarctica, the now warmer waters of this current can do

little to effect the great ice sheets. Here Sunke’s study

identifies the crux of the problem — the waters of the Circumpolar

Deep Water are surging up over the continental shelf margins to

contact Antarctica’s sea fronting glaciers and ice shelves with

increasing frequency.

In

some cases, these warm waters have risen by more than 300 feet up the

continental shelf margins and come into direct contact with Antarctic

ice — causing it to rapidly melt. This process is most visible in

the Amundsen Sea where an entire flank of West Antarctica is now

found to be undergoing irreversible collapse. The great Pine Island

Glacier, the Thwaites Glacier and many of its tributaries altogether

composing enough ice to raise sea levels by 4 feet are now at the

start of their last days. All due to an encroachment of warm water

rising up from the abyss.

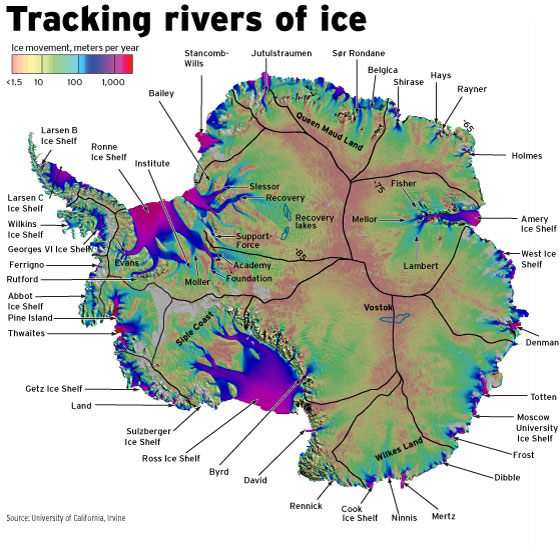

(Antarctic rivers of ice. Rising and warming waters from the Circumpolar Deep Water along continental margins have been increasingly coming into contact with ice shelf and glacier fronts that float upon or face the surrounding seas. The result has been much higher volumes of melt water contributions than expected from Antarctica. Image source:University of California.)

But

the warm water rise is not just isolated to the Amundsen Sea. For

Sunke also found that the warm water margin in the Weddell Sea on the

opposite flank of West Antarctica was also rapidly on the rise. From

1980 to 2010, this warm water zone had risen from a depth of about

2100 feet to less than 1100 feet. A rapid advance toward another

massive concentration of West Antarctic ice.

The

impacts of a continued rise of this kind can best be described as

chilling.

Sunke

notes in an interview with National

Geographic:

If

this shoaling rate continues, there is a very high likelihood that

the warm water will reach the Filchner Ronne Ice Shelf, with

consequences which are huge.

Filchner

Ronne, like the great Pine Island Glacier, has been calving larger

and larger ice bergs during recent years. Should warm waters also

destabilize this vast ice shelf another 1.5 feet of sea level rise

would be locked in due to its direct loss. Including the massive

inland glaciers that Filchner Ronne buttresses against a seaward

surge, much larger than the ones near the Amundsen sea, would add a

total of 10 feet worth of additional sea level rise.

Together,

these destabilized zones would unleash much of West Antartica and

some of Central Antartica, resulting in as much as 14 feet of sea

level rise over a 100 to 200 year timeframe. This does not include

Greenland, which is also undergoing rapid destabilization, nor does

it include East Antarctica — which may also soon come under threat

due to the encroachment of warm waters rising from the depths.

Are

IPCC Projected Rates of Sea Level Rise Too Conservative?

The

destabilization of glaciers along the Amundsen sea, the imminent

threat to the Filchner Ronne Ice Shelf, and the less immediate but

still troubling threat to East Antarctica’s glaciers, together with

a rapidly destabilizing Greenland Ice Sheet, calls into question

whether current IPCC predictions for sea level rise before 2100 are

still vlid.

IPCC

projects a rise in seas of 1-3 feet by the end of this Century. But

much of that rise is projected to come from thermal expansion of the

world’s oceans — not from ice sheet melt in Antarctica and

Greenland. Current rates of sea level rise of 3.3 milimeters each

year would be enough to hit 1 foot of sea level rise by the end of

this Century. However, just adding in the melting of the Filchner

Ronne — a single large ice shelf — over the same period would add

4.4 milimeters a year. Add in a two century loss of the Amundsen

glaciers — Pine Island and Thwaites — and we easily exceed the

three foot mark by 2100.

Notably,

this does not include the also increasingly rapid loss of ice coming

from Greenland, the potential for mid century additions from East

Antarctica, or lesser but still important additions from the world’s

other melting glaciers.

Such

more rapid losses to ice sheets may well reflect the realities of

previous climates. At current CO2e levels of 481 ppm (400 ppm CO2 +

Methane and other human greenhouse gas additions) global sea levels

were as much as 75-120 feet higher than they are today. Predicted

greenhouse gas levels of 550 to 600 ppm CO2e by the middle of this

century (Breaking 550 ppm CO2 alone by 2050 to 2060) are enough to

set in place conditions that would eventually melt all the ice on

Earth and raise sea levels by more than 200 feet. For there was no

time in the past 55 million years when large ice sheets existed under

atmospheric CO2 concentrations exceeding 550 parts per million.

Glaciologist

Eric Rignot has been warning for years that the IPCC sea level rise

estimates may well be too conservative. And it seems that recent

trends may well bear his warnings out. If so, the consequences to

millions of people living along the world’s coastlines are stark

and significant. For the world, it appears we face the increasing

likelihood of a near-term inland mass-migration of people and

property. A stunning set of losses and tragedy starting now and

ongoing through many decades and centuries to come.

Links:

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.