Smashing Through 490 — Fragmenting Prospects for Avoiding 2 C Warming

“The

IPCC indicated in its fourth assessment report that achieving a 2 C

target would mean stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations in the

atmosphere at around 445 to 490 ppm CO2 equivalent or lower. Higher

levels would substantially increase the risks of harmful and

irreversible climate change.”

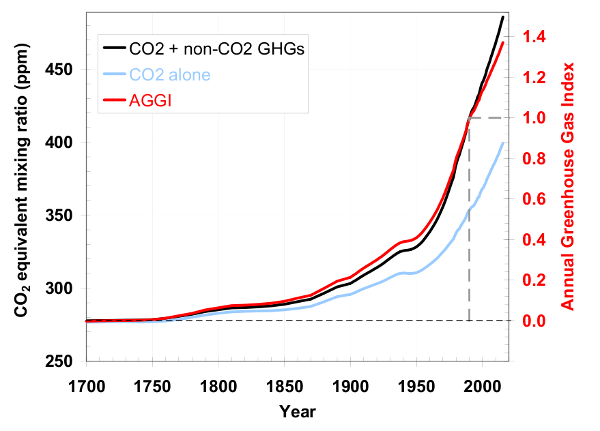

(NOAA’s

greenhouse gas index shows that CO2e concentration for 2015 averaged

485 ppm. Given recent rates of rise, the 2016 average should be near

490 ppm CO2e. At the latest, this key threshold will be crossed some

time during 2017. Image source: NOAA’s

Earth Systems Research Laboratory.)

*****

12

August, 2016

There

are a few things we know about climate change that should really keep

us up at night. The first is that the world is warming, and this

warming of the Earth, in so many ways, is dangerous to human beings

and all the other innocent creatures living here.

The

second is that, over recent years, this warming has been very rapid.

In the three years from 2014 through 2016, the Earth’s atmospheric

temperature is likely to have increased by 0.2 degrees Celsius or

more to around 1.2 C above 1880s levels. When thinking about this in

absolute terms, it doesn’t sound like much. But in geological

terms, this is very rapid warming, especially when you consider that,

at the end of the last ice age, it took about 400 years to produce a

similar amount of atmospheric temperature gain.

What

all this boils down to is that as global temperatures have spiked,

we’ve rapidly crossed an established climate threshold into a far

more geophysically dangerous time.

Surging

Levels of Heat-Trapping Gasses

405

parts per million carbon dioxide.

That’s about the average level of CO2 accumulation the Earth’s

atmosphere will see by the end of 2016, due primarily to fossil-fuel

burning. It’s a big number. The Earth hasn’t seen a number like

that in millions of years. But 405 ppm CO2 doesn’t tell the whole

story of heat-trapping gasses in the atmosphere. To do that, we have

to look at another number — carbon dioxide equivalent or CO2e.

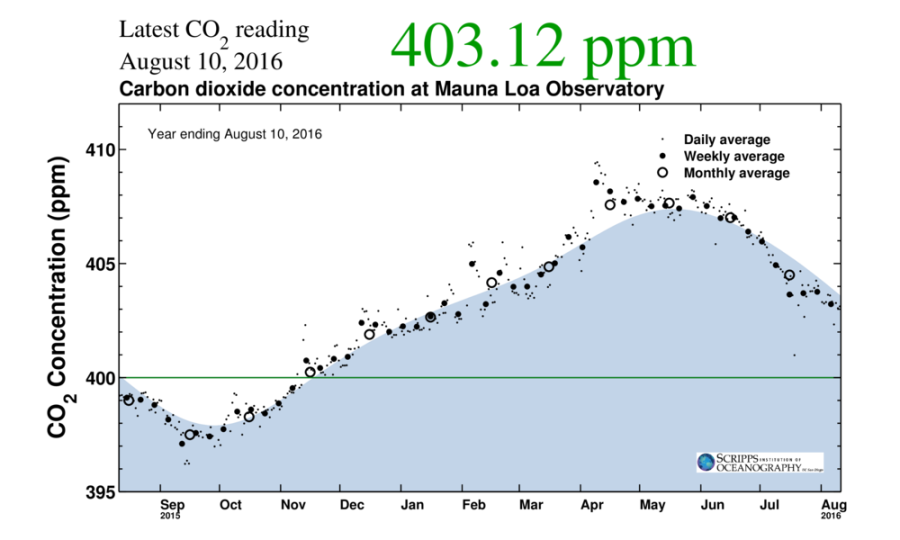

(During

a typical September and October, daily or weekly values may briefly

dip below 400 ppm CO2, as detected at the Mauna Loa Observatory. But

after September-October 2016, it’s unlikely that you or I will ever

see such low levels of CO2 from that measure again in our lifetimes.

Image source: Scripps

Institution of Oceanography.)

490

ppm CO2e.

That’s about the total amount of CO2-equivalent heat forcing from

all the human-added greenhouse gasses like CO2, methane, various

nitrogen compounds, and other gaseous chemical waste that the Earth’s

atmosphere will see by late 2016 to early 2017.

Why

is this a big deal?

Four

reasons —

First,

hitting 490 CO2e crosses the Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change‘s

(IPCC) lowest climate threshold. If this were a highway, and climate

change were a collision, we’d now be careening through the first

guardrail.

Second,

490 CO2e represents significant current and future warming (and

there’s good reason to believe that IPCC’s

estimates of that warming may

be a bit conservative).

Third,

it signifies that we have now fully entered the era of

catastrophic climate change, with some bad climate outcomes almost

certainly locked in as a result. We see a number of these instances

now in the form of extreme rainfall events, extreme drought, coral

bleaching, sea ice and glacial melt, threatened crops, ocean anoxia

and dead zones, widespread harmful algae blooms, ocean acidification,

and expanding infectious disease ranges. However, what we are

experiencing now is just the tip of the (melting) climate change

iceberg if we do not rapidly respond.

Fourth,

if we were never really aware before that we very urgently need to

get serious about swiftly cutting fossil-fuel emissions, protecting

and regrowing forests, and working to help people to adapt to climate

change, then this is our wake-up call.

Crossing

the First Climate Threshold — 490 ppm CO2e

How

did 490 ppm CO2e become a climate milestone? In short, it represents

the threshold at which the first of four global-warming scenarios is

basically locked in.

To

understand this more, we need to take a closer look at these four

scenarios, which were established by the IPCC in 2007. The IPCC calls

these scenarios Representative

Concentration Paths or RCPs.

The four potential pathways are informed by the amount of fossil

fuels potentially burned through the year 2100, the levels of CO2e

heat-trapping gasses in the atmosphere as a result, and how much the

world consequently warms over this timeframe.

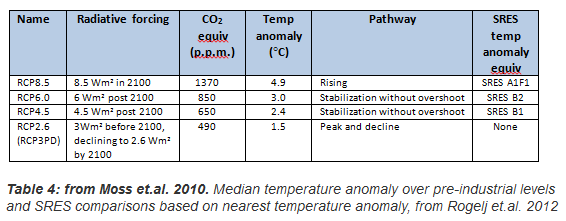

RCPs

range from 2.6 to 8.5 watts per meter squared, with these

measurements indicating the amount of added heat from the greenhouse

gas additions trapped at the top of the atmosphere. A more

direct measure is to look at the total greenhouse gas thresholds for

each scenario. Broken down, the four RCP pathways represent 490 ppm

CO2e (RCP 2.6), 650 ppm CO2e (RCP 4.5), 850 ppm CO2e (RCP 6.0), and

1370 ppm CO2e (RCP 8.5). For reference, atmospheric CO2e levels just

prior to the start of large-scale fossil fuel burning were around 300

ppm. By comparison, 1370 ppm CO2e is about equivalent to the levels

during some of the worst hothouse mass extinctions the Earth has

experienced.

In

a nutshell, RCPs represent potential warming scenarios. A

middle-range temperature increase estimate by the year 2100 for each

scenario can be seen below in this table provided by Skeptical

Science:

Developed

at the IPCC’s 2007 meeting, these RCPs also describe a range of

potential human civilization responses to global warming. RCP 2.6

allows for fast emissions cuts beginning at the time of the 2007

meeting. These cuts would swiftly level off and then reduce

fossil-fuel emissions and ultimately generate one of the milder

warming scenarios. The IPCC envisioned that warming would remain near

1.5 C this century under these emissions cuts. Scientists hoped this

scenario would allow the avoidance of most of climate change’s bad

outcomes.

RCP

4.5 assumes somewhat less aggressive emissions cuts, with

fossil-fuel burning and related carbon emissions peaking near 15

billion tons per year by the mid-2040s. Stronger warming is locked in

with this scenario — about 2.4 C according to IPCC — and

scientists were doubtful that serious climate impacts could be

avoided.

(We’ve

pretty much missed the window for the IPCC’s mildest possible

climate scenario, RCP 2.6, which would have required strong policies

and policy support almost immediately following the IPCC’s 2007

meeting. Image source: Skeptical

Science.)

RCP

6.0 shows emissions cuts that are slow to unfold. Global carbon

emissions would peak around 19 billion tons per year by 2060 and then

rapidly drop off. Warming under this scenario is considerable,

hitting 3 C by the end of this century. So much warming and such high

levels of greenhouse gasses would result in some seriously bad

outcomes.

The

final pathway, RCP 8.5, represents an absolute nightmare climate

scenario. Under this path, real emissions cuts are not achieved.

Despite growth in renewable energy, all energy

use continues to grow as well, including fossil fuels. As a result,

in this scenario, the IPCC expects the Earth to warm by a

catastrophic 4.9 C by 2100.

In

the context of understanding climate change, particularly for someone

interested and patient enough to read the IPCC reports, the various

RCP scenarios were a real help in exploring climate change options

and outcomes. They helped many scientists and policymakers provide

clear warnings and rewards for action by governments, the public, and

business leaders.

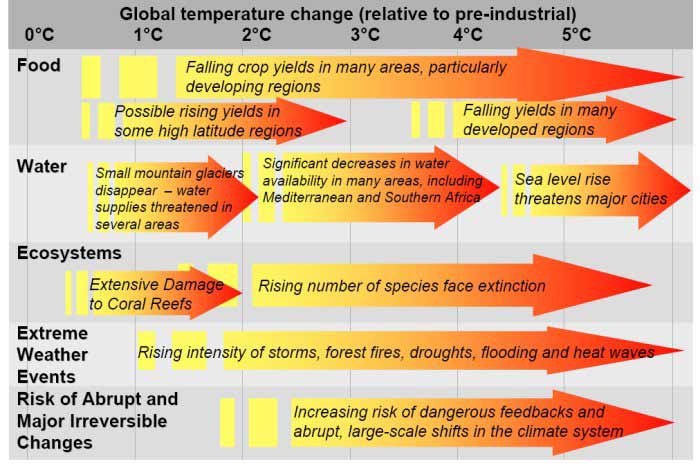

(Climate

change produces multiple difficult-to-predict impacts. As

temperatures rise, conditions grow ever more extreme. In the graph

above, it’s worth noting that sea-level rise is already an issue

for many cities and regions including numerous Pacific islands,

Bangladesh, the Indus Delta region, South Florida, New Orleans, New

York, and the various low-lying coastal and river delta regions

around the world. Image source: Federal

Highway Administration.)

But

despite very clear communication and activism from scientists like

Dr. James Hansen, policy bloggers like Joe Romm, and climate

activists like Bill McKibben, overall global emissions policy has not

moved swiftly enough to stay within the RCP 2.6 pathway in the 9

years since its creation. In fact, decent global emissions reduction

policies didn’t begin to universally take hold until recently, in

2014 and 2015, and those implemented were often ardently opposed by

fossil fuel-related political interests in countries like Australia,

Great Britain, Germany, Canada, and the United States.

As

a result, emissions stayed near or just below worst-case pathway

ranges (RCP 8.5). As of this year, the window for achieving the RCP

2.6 scenario — or the mildest and most optimistic warming scenario

— appears to have closed.

Possibly

More Warming From 490 CO2e Than We Feared

Hitting

490 CO2e in 2016 means that the 1.5 C warming IPCC predicted for this

amount by 2100 is almost certainly locked in. With the world hitting

near 1.2 C above 1880s temperature averages in 2016, some reasonable

questions have been raised, the most relevant being if 490 ppm CO2e

will result in more warming than IPCC predicted.

To

be fair, the 1.5 C figure above is a simplification of model

predictions ranging from about 0.9 C to around 2.3 C during this

century under a 490 ppm CO2e forcing. However, since we’ve already

surpassed the lower portion of this range, and we’re barely into

the beginning of this century, it appears that some of the lower

sensitivity model runs were rather far off the mark.

Moreover, paleoclimate

proxy temperature data indicates

that 490 ppm CO2 during the Middle Miocene produced warming in the

range of 4 C long-term (over hundreds of years). Given this implied

long-term impact, and coupled with annual readings that are already

in the 1.2 C range, it’s possible to infer an ultimate warming

closer to 2 C by 2100 from a maintained 490 ppm CO2e. Hitting such a

mark would only require about 0.11 C warming per decade — a rate of

decadal warming about 40 percent slower than the temperature rise

seen from the late 1970s through the 2010s.

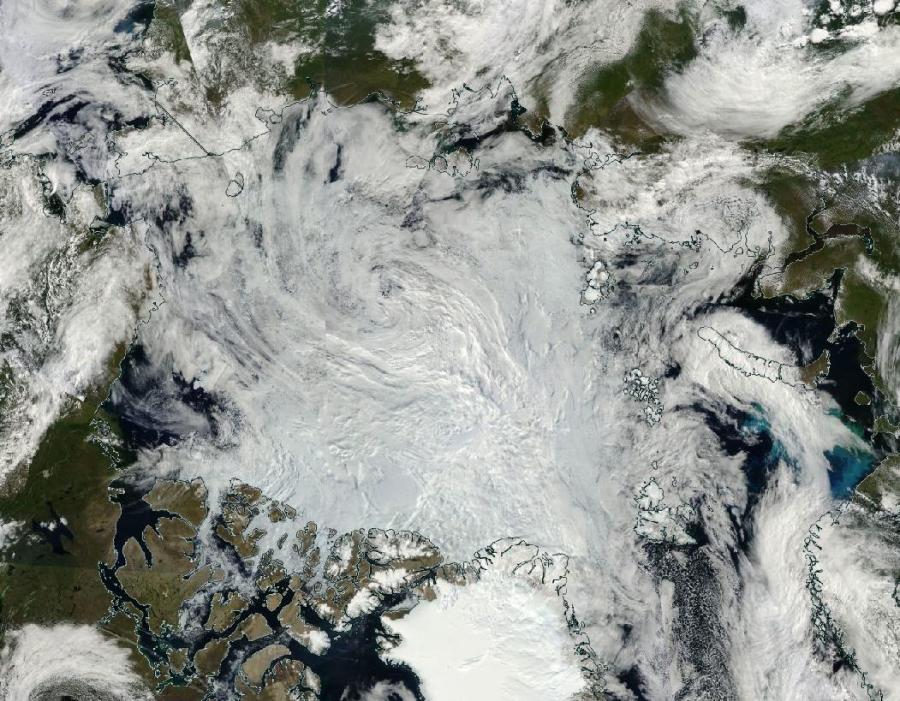

(Amplifying

feedbacks due to loss of sea ice reflectivity in the Arctic and

Antarctic, reduced carbon-store uptake and carbon-store emissions can

result in an overall greater sensitivity to an initial heat forcing

such as the current 490 ppm CO2e. Paleoclimate proxies hint that

these feedbacks may cause the Earth System to be more sensitive than

IPCC models currently indicate. Image source: LANCE

MODIS.)

The

paleoclimate-implied warming from the other climate scenarios is

likely higher as well. RCP 4.5 probably hits closer to 3 C under such

a climate sensitivity range. RCP 6.0 probably sees 4 to 4.5 C warming

by 2100. And the worst-case RCP 8.5 probably achieves closer to 6 C

warming.

It’s

for these and other reasons that some scientists say that avoiding

1.5 C at this time is probably impossible. Meanwhile, it’s pretty

reasonable to say that avoiding 2 C presents a huge challenge

requiring a very rapid response, a goal that will probably require

reducing the atmospheric CO2e levels below their current ranges.

CO2e

Increasing by 3 ppm Per Year

Human

beings are still dumping massive volumes of carbon into the

atmosphere. Carbon emissions are still near record-high levels. As a

result, atmospheric CO2e levels are rising by about 3 ppm or more

each year. For 2016, CO2 alone may rise by 3.4 ppm or more, and CO2e

may jump by more than 4 ppm — to hit near 490 ppm CO2e. This is due

in part to the 2015-2016 El Nino’s cyclical warming of the

Equatorial oceans, forests, and lands on top of the

already-strengthening heat of human warming. And

this added heat reduces the ability of these carbon sinks to take in

CO2.

Even

if this rate of CO2e rise is just maintained, it’s possible that

we’ll see 1.5 C warming not by the end of this century, but by the

early 2030s. And as the world heats up, it’s likely we’ll see

additional emissions coming as carbon

sinks become stressed and stop taking in such high volumes of

greenhouse gasses or even turn into sources.

The

result is that the challenge presented to us now is far greater, far

more urgent than that of 2007. We risk, over the next few

decades, locking in not just 2 C warming, but 3 C warming or more if

we do not act swiftly and seriously. And with 1.5 C warming coming

with almost 100 percent certainty, we need to ramp up climate-change

mitigation strategies as well as provide aid and succor for the

increasing harms, dislocations, and inequalities that will likely

emerge.

Links:

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.