We've left the La Niña period behind and are now moving into an El Niño period

Climate.gov,

2 May, 2018

Sayonara, sweetheart

Onward!

Our next order of business is to bid

adieu to La Niña,

as the sea surface temperature in the tropical Pacific returned to

neutral conditions in April—that is, within 0.5°C of the long-term

average.

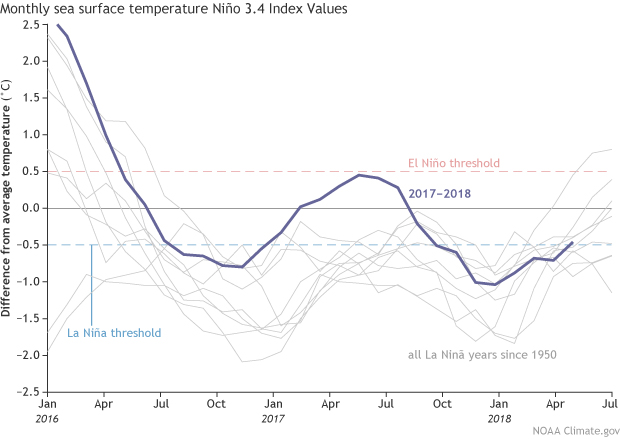

Monthly

sea surface temperature in the Niño 3.4 region of the tropical

Pacific compared to the long-term average for all multi-year La Niñas

since 1950, showing how 2016–18 (blue line) compares to other

events. Multi-year La Niña events are defined as at least 2 years in

a row where the La

Niña criteria are

met.

Both continuous events, when the Oceanic

Niño Index (ONI)

remained below -0.5°C, and years when the ONI warmed mid-year before

again cooling, are included here. For three-year events, both years

1-2 and 2-3 are shown. Climate.gov graph based on ERSSTv5 temperature

data.

The

temperature of the water below the surface remained above-average,

as the large area of warmer-than-average subsurface waters continued

to move slowly to the east (a downwelling

Kelvin wave).

This warm area will continue to erode the remaining cooler surface

waters over the next few months.

The

tropical atmosphere is also looking mostly neutral. Rainfall over

Indonesia was below average, and the near-surface winds were close to

average, as La Niña’s strengthened Walker

circulationfaded.

Memories

Let’s

look back on the past few months, to see how much February–April

global temperature and rain patterns reflected those expected

(temperature, rain)

during La Niña! The maps linked

here show both the changes expected during ENSO and the observed

temperature trends,

and the combination of the two.

Some of the other weather and climate patterns at play

over the past few months included the Madden-Julian

Oscillation,

a sudden

stratospheric warming,

and, of course, global

warming.

As we’ve documented here at the ENSO Blog, these patterns have

their own distinct effects on temperature and precipitation patterns,

and attributing weather events to climate patterns is a complicated

science.

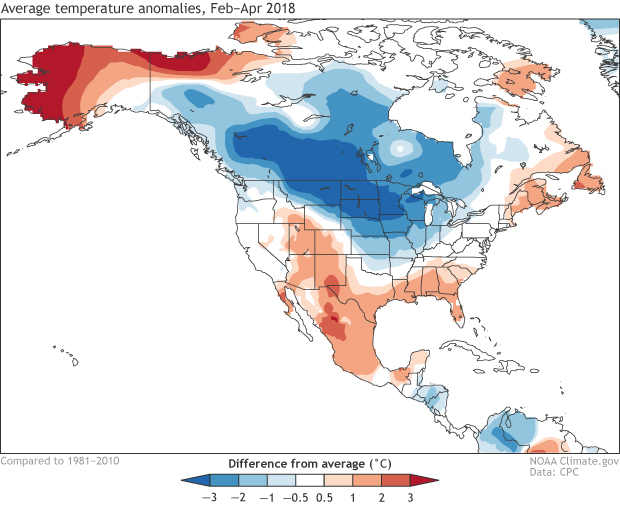

That

said, the 2018 late winter/early spring period over North America

showed many similarities to what we’d expect during La Niña. In

North America, February–April during La Niña tends to be cooler

than average in the northern half of the US and through Canada, and

warmer than average through Texas and the South and into Mexico. When

you add in the temperature trend during

this time of year (slight cooling though the northern Midwest,

warming across the Southwest), you get a pattern much like that

observed during 2018.

February–April

2018 surface temperature patterns, shown as the difference from the

long-term mean. Climate.gov figure from CPC data.

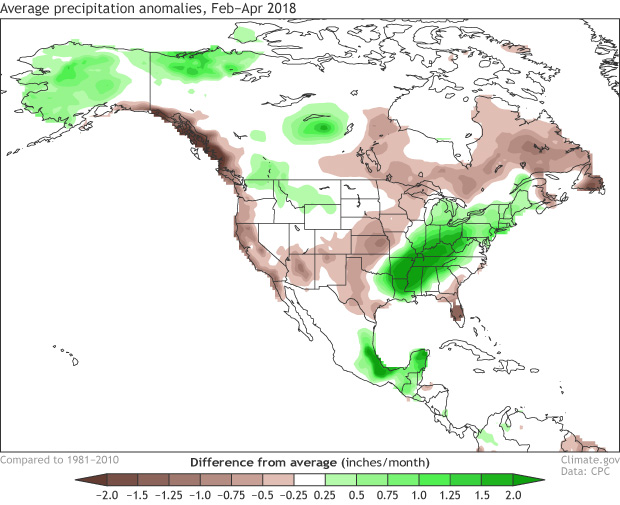

Also

typical in February–April during La Niña conditions is more

rain than average through the Ohio valley, and drier weather in

Florida and through the U.S. Southwest, generally similar to what was

observed this year. The lack of rain in the Southwest has contributed

to the extreme drought and wildfire conditions

this year.

February–March

2018 rain and snow patterns, shown as the difference from the

long-term mean. Climate.gov figure from CPC data.

What the future holds

Enough

looking back! Let’s look forward! As we’ve discussed

before,

making ENSO forecasts in spring is especially complicated. It’s a

time of transition, and small changes in conditions can have large

effects down the road. This month’s ENSO forecast finds it most

likely that neutral conditions will last through the summer and into

early fall. Most of the climate models support this.

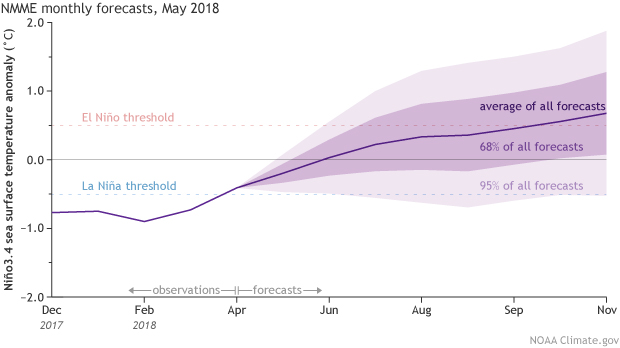

Climate

model forecasts for the Niño3.4 Index, from the North

American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME).

Darker purple envelope shows the range of 68% of all model forecasts;

lighter purple shows the range of 95% of all model forecasts. NOAA

Climate.gov image from CPC data.

What

about next winter?? The forecast

possibility of El Niño nears

50% by the winter, as many of the computer models are trending to

warmer tropical sea surface conditions in the later months of 2018.

In the historical

record (dating

back to 1950) we’ve had 7 two-year La Niña events. These

events have been followed by El Niño twice: 1972 and 2009. The

probability of remaining in neutral conditions is about 40%,

something that has happened three times in the record: 1956, 1985,

and 2012. Less likely is a return to La Niña conditions—that

scenario is given about a 10% chance. A three-peat La Niña isn’t

impossible, at all, and has occurred twice in the historical record:

1973–76, and 1998–2001.

One

thing we can be certain of is that forecasters are looking forward to

next month, when the models are increasingly getting past the spring

predictability barrier and are more reliable. See you then!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.