If

There’s a Recession, It Will Be Made in China

The

country’s integration into the world economy drove three decades of

growth. That’s over.

Bloomberg,

24

August, 2019

It’s

official -- the yield curve has now definitely inverted, meaning that

one of the most reliable signals of an impending recession is now

flashing warning signs. For a while, the inversion was only partial;

some spreads between long-term and short-term bond yields fell below

zero, but the spread between 10-year and 2-year Treasury bonds

remained positive. That too dipped briefly into negative territory:

Loud But Not So Clear

Two

of three different measures of the yield curve have inverted.

An

inverted yield curve means that investors expect interest rates to

fall, which typically happens in a contraction. It tends to take a

while, though -- 12 to 18 months. That rule of thumb could mean a

recession anywhere between March 2020 and February 2021. And it’s

even possible that the yield curve could be giving a false signal. So

although the yield curve inversion isn't good news, it’s no cause

for panic. For now, U.S. economic data such as retail sales and

jobless claims are holding up reasonably well.

Anyway,

an inverted yield curve is just a signal -- it doesn’t cause

recessions, any more than a rooster’s crow causes the sun to rise.

Some argue that the inversion could be a self-fulfilling prophecy,

inducing pessimism that leads companies to cut spending and thus

causing a real downturn. But the surge of pessimism when the yield

curve briefly inverted earlier this year failed to derail the

economy, and it’s hard to see why this episode would be different.

If

a recession happens, therefore, it probably will be the result of

some shock. But what could that be? Paul Krugman has suggested the

cause might be a smorgasbord of small factors -- the trade war,

weakness in the housing market, the end of the demand boost from the

tax cuts and so on. That’s certainly possible. But many of those

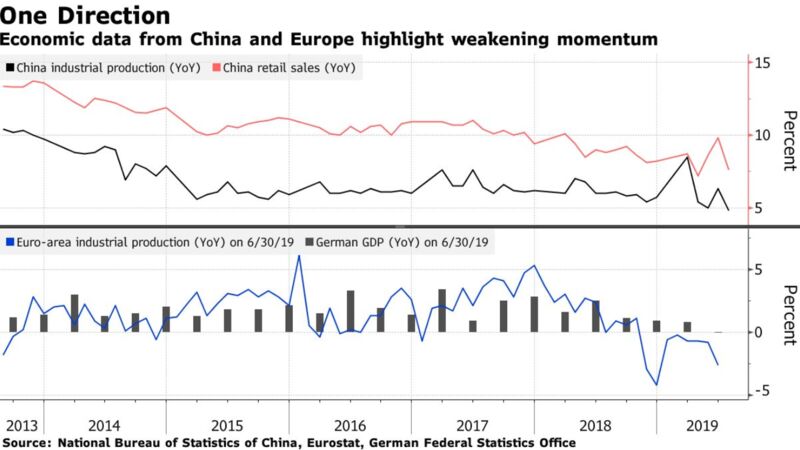

factors are specific to the U.S. The bigger concern is that the

global economy is looking even weaker than the U.S. China and

Germany, two export powerhouses and major U.S. trade partners, are

both slowing a lot:

This

suggests that a U.S. recession, if it comes, will be part of a world

slowdown. Americans tend to think of their own markets and their own

consumption as the driver of both booms and busts. That may not be

true this time around.

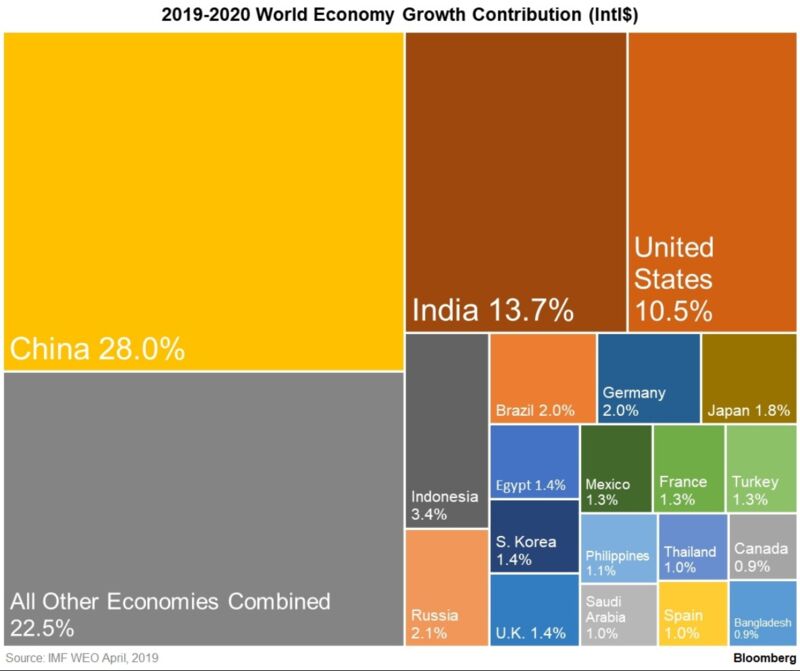

Instead,

any recession may be made in China. In recent years, China has

contributed more to global growth than any other country, and it was

projected to do the same in the years to come:

Thus

when China sneezes, to modify an old saying, the world may now catch

a cold. From 2010 to 2017, China contributed 31% of global

consumption growth, and some companies have staked their futures on

the promise of a billion Chinese consumers buying their products. A

drop in Chinese purchases won’t just reduce sales for businesses in

the U.S. and other rich countries -- it will cause multinationals to

cut their investment plans.

There

are several things threatening China’s growth. The most obvious is

the trade war. The one-two punch of U.S. tariffs and restrictions on

exports to Chinese technology companies appears to have made Chinese

manufacturers more cautious about investing for the future:

But

there are longer-term factors as well. In order to weather the Great

Recession, China shifted its focus from export-oriented manufacturing

to domestic real estate and infrastructure, and from private

companies to state-owned enterprises. That probably caused

productivity growth to slow. Meanwhile, China’s working-age

population is now shrinking and its supply of surplus rural labor has

dried up. Retooling its economy to produce less pollution and cut

greenhouse emissions will slow growth as well, even if the long-term

environmental effect is worth it.

But

it’s not just a Chinese recession that threatens the world economy.

The trade war, along with looming geopolitical tensions between the

great powers, are threatening to open a rift between China and the

rest of the world economy. Tariffs have global manufacturers

scrambling to move production from China to countries such as Vietnam

and Bangladesh. Companies, both Chinese and otherwise, are being

forced to decide whether to consolidate their supply chains inside

China or go elsewhere.

This

decoupling will probably be protracted, and costly. The past 30 years

have seen the construction of a global trading system centered around

a China-U.S. axis, and now that structure is breaking down. In

addition to the cost of reorganizing supply chains and the economic

inefficiency introduced by the separation, companies are facing deep

uncertainty about where they will be able to source their inputs and

sell their products.

So

the inverting U.S. yield curve may be signaling the start of a

recession that was long in the making, as the global expansion driven

by the integration of a fast-growing China into the global economy

comes to an end. This will combine with the direct impact of tariffs

to inflict pain on the U.S. economy. But the fallout in the rest of

the world, and especially in China, may be even more severe. Out of

all the possible reason for why a downturn is on the way, this is the

most concerning and the most plausible.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.