While we’re still talking about trolls

Climate Deniers’ Top 3 Tactics

Climate

deniers don’t just want to deny global warming and its danger. They

want you to

deny it too.

But

man-made climate change is real, the danger is extreme, so they have

to use guile to persuade you otherwise. There are three

tried-and-false tactics they use often, and to great effect. Let’s

take a close look at these misdirection methods, so you can arm

yourself for defense against the dark arts.

#3:

REJECT THE DATA

Climate

deniers don’t like what the data say. What they probably hate most

is the temperature data — especially at Earth’s

surface (where we live) — because it shows so plainly and obviously

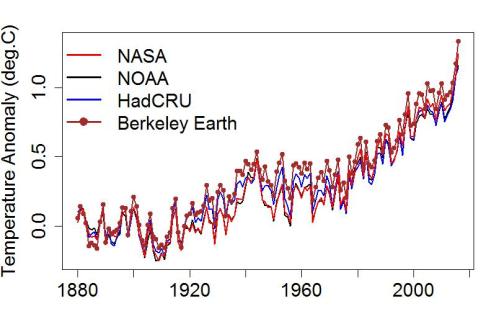

that the world is heating up. Here are the three best-known

global-average surface temperature data records (yearly averages

since 1880), from NASA, NOAA (the National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration), and HadCRU (the Hadley Centre/Climate Research Unit

in the U.K.):

They

all tell pretty much the same story: Earth is heating up.

Pinning

down global average temperature change is a complicated business. You

have to gather data from around the world, including thermometer

readings from thousands of surface stations for land areas and sea

surface temperature measurements from ships and from satellites. You

have to average them properly, in a way that doesn’t over-emphasize

regions with lots of observations but underplay regions more sparsely

observed (a process sometimes called “area-weighting”). You need

to remove the seasonal cycle, because we’re not interested in

whether summer is hotter than winter, we want to know whether the

world as a whole is heating or cooling. You have to watch for things

like station moves where temperature seems to

change only because the station was moved to a hotter or colder

location. Truly, it’s a complicated business.

The

longer they’ve been doing it, the better they’ve gotten at it. In

particular, they’ve learned to spot the signs of data problems and

make adjustements to compensate. As a result, they’re a lot better

at it now than they were just a few decades ago.

But

because there are “adjustments” — whose only purpose is to make

thing better by compensating for known problems — deniers have

seized on that word to claim that the scientists doing it were

perpetrating a fraud, that adjustments were only to introduce false

warming into the record.

Richard

Muller, a physicist at Berkeley University, thought that maybe they

were right about that — he was highly suspicious

of the surface temperature data. He decided to find out for himself,

by organizing a team to go back to the original, unadjusted

data, and use the most sophisticated and mathematically sound

procedure for estimating a world-wide average, one which didn’t

allow any way to make the results “lean” one way or the other to

introduce a bias toward cooling or warming. The effort is called

the Berkeley Earth Surface

Temperature project.

Climate

deniers were thrilled — they waited in anticipation of genuine

scientists, using the best available methods, finally showing that

the existing records were wrong.

The

admiration of climate deniers for the Berkeley Earth Surface

Temperature project didn’t last long. It vanished into thin air as

soon as the results were announced. That’s when the climate denier

community turned on Richard Muller like a pack of wolves, because the

Berkeley Earth Surface Temperature project, the fakeproof method,

showed that the

existing data sets got it right all along.

Muller himself had this to say in a 2012

op-ed in the New York Times:

CALL me a converted skeptic. Three years ago I identified problems in previous climate studies that, in my mind, threw doubt on the very existence of global warming. Last year, following an intensive research effort involving a dozen scientists, I concluded that global warming was real and that the prior estimates of the rate of warming were correct. I’m now going a step further: Humans are almost entirely the cause.

And

how does the new Berkeley Earth data set compare to the others? Like

this:

Climate

deniers don’t just use this tactic on temperature records; when

data disagree with their narrative they’ll attack the data.

Far too often, they won’t just say the data are

mistaken, they’ll accuse the scientists who put it together of

fraud. It’s reprehensible.

Climate

deniers like to call themselves “skeptics,” but they’re not.

What’s the difference? I think Neil deGrasse Tyson said it best:

“A skeptic will question claims, then embrace the evidence. A denier will question claims, then reject the evidence.”

#2:

DISTRACT FROM THE TREND WITH FOCUS ON FLUCTUATIONS

Almost

all data is a combination of trend, which has

persistence, and fluctuation, which doesn’t last. The

trend reveals how climate is changing, but the

fluctuations are weather, and just because climate

changes, doesn’t mean we won’t still have weather. Fluctuations

go up and down and down and up — they just won’t stop — but

they never really get anywhere.

Climate

scientists can tell you, it’s the trend that

matters. Heat waves, flood, drought and the like are things we’ve

always had to deal with, and they spell trouble. But when they

get more frequent, and more severe,

it can be disastrous. It costs money, it costs jobs, it costs lives.

Deniers

don’t want you to know how the trend is going, so they go out of

their way to shout about fluctuations that go the other way. Maybe

the most infamous example is when Oklahoma senator James Inhofe

carried a snowball onto the floor of the U.S. senate one day to try

to ridicule global warming. He ended up ridiculing himself, because

the idea that you can discredit global warming because you happened

to find some cold weather — in winter, no less — is truly

ridiculous. As in, worthy of ridicule.

Temperature

is one of those things that fluctuates. It can show large swings from

day to day, from month to month, even from year to year. But there’s

also a trend, which is upward — it’s called global

warming. Lately deniers have been taking temperature fluctuations

that happen to go downward and braying about “global cooling.” Of

course the fluctuations don’t last — but they still accomplish

their goal of creating doubt in the minds of the scientifically

naive.

Christopher

Booker writes for the British newspaper The Telegraph. He

recently included a comment about England’s meteorological office

acquiring a new computer for their weather and climate simulations,

in which he had this to say:

“Only gradually since 2007, when none of them predicted a temporary fall in global temperatures of 0.7 degrees, equal to their entire net rise in the 20th century, have they been prepared to concede that CO2 was not the real story.”

— Christopher Booker, U.K. Telegraph, 22 October 2016.

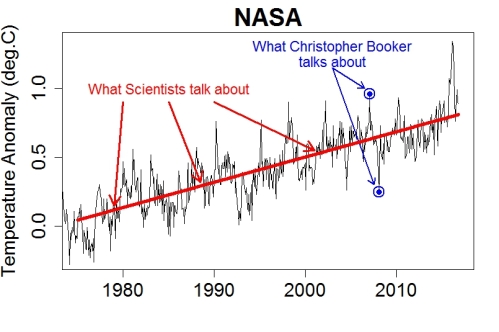

It

that true? Did global temperature actually fall far enough to negate

the entire 20th-century rise? Here’s Earth’s average temperature

change each month from 1880, according to NASA:

If

we zoom in on the last 40 years or so, starting about 1975, we can

easily see what it is Christopher Booker is talking about:

He’s

talking about a couple of fluctuations. If you compare an especially

high fluctuation to an especially low fluctuation, you might convince

yourself that temperature is falling fast.

But

a fluctuation is not a trend. Trends have some persistence;

fluctuations don’t last. Climate scientists tell us that it’s the

trend that matters — that’s why it’s what they talk about:

Another

example: about a week ago David Rose had an article in the U.K. Daily

Mail with its focus on a “sudden drop” in global

temperature. Rose searched far and wide to find a data set he could

use to make that claim, and the best he could come up with was

satellite data for the lower atmosphere (not at the surface) over

land areas only (excluding the 2/3 of the world covered by ocean).

His story was repeated by others in the U.K. Spectator and

the alt-right propoganda-driven Breitbart News.

What’s

fascinating is what they chose to focus on: some fluctuations which

they seemed to think were worth shouthing about, with no mention of

the trend. Here, in blue, are the fluctuations they made

such a fuss about, and in red is the trend they didn’t want to

discuss:

Fluctuations

will always be with us, they’re part of nature. But the rising

trend of global temperature that we’ve been seeing is man-made.

According to the overwhelming majority of climate scientists, this

trend spells trouble. And the reason? Mainly, it’s CO2.

We

now come to the most common, most pernicious, and probably most

effective climate denier tactic:

#1:

CHERRY-PICKING

On

April 15, 2013, Lawrence Solomon published a brief article

in the Financial

Post suggesting

that sea ice in the Arctic wasn’t really declining, that there was

no trend toward persistent long-term melting. He started with this:

Arctic sea ice back to 1989 levels

Yesterday, April 14th, the Arctic had more sea ice than it had on April 14,1989 – 14.511 million square kilometres vs 14.510 million square kilometres, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center of the United States, an official source.

His

opening sentence is one of the most extreme examples

of cherry-picking: showing or talking about some evidence

that supports your claim, while ignoring or rejecting evidence that

contradict you.

He

went on to add a couple more cherry-picked “facts” for good

measure. Then he ended with this:

“The only evident trend in the ice, as in the weather, is variability.”

It

all sounds pretty convincing, doesn’t it? Arctic sea ice was no

more extensive on that day than it was 24 years ago! Plus, he

actually mentions the words “trend” and “variability” — how

scientific.

The

following day (April 16, 2013) I posted this graph showing all the

available “sea ice extent anomaly” data from the National Snow

and Ice Data Center (yes, an official source):

In

case you’re wondering what’s happened since then, it’s this:

The

red line is an estimate the trend — the one that

Lawrence Solomon said isn’t “evident.”

This

particular example is also a case of tactic #2: distract from the

trend by focus on fluctuation. It’s executed by the never-ending

tactic of cherry-picking: discuss evidence that supports your claim

while ignoring or concealing evidence that contradicts you.

The

most frequent target of cherry-picking is temperature data. Here, for

instance is senator Ted Cruz’s favorite temperature graph:

I

t

certainly looks like there’s been no global

warming! But remember that data is a combination

of trend and fluctuation. Fluctuations

sometimes go down, which can make an upward trend look downward,

even when that trend — which we call global warming — hasn’t

stopped or even slowed. What deniers do is cherry-pick — find a

time span which starts with a large upward fluctuation, maybe even

ends with a large downward fluctuation, to create the false

impression of a downward trend.

In

1997-1998 we had a particularly strong el Niño, one of

the factors that can cause an especially large upward

fluctuation. That’s why climate deniers start so many

temperature graphs with 1997-1998 — it’s the large

upward fluctuation they need to give a false impression of trend.

But

that’s not the only time span one can cherry-pick to show

fluctuation and claim it’s a trend. There are many, which led to a

now-famous animated graph from the website Skeptical

Science:

No

matter how temperatures change, as long as there are fluctuations

deniers will be able to cherry-pick some time span to look like

their false claim. And there will always be fluctuations.

What

if we didn’t cherry-pick the time span? The data in Ted Cruz’s

graph starts back in 1979, well before 1997, and we’ve got some

more data since he showed it in his latest senate hearing. Here’s

the whole story:

T

he

red box shows the part included in Ted Cruz’s graph. The

interesting part, that reveals the upward trend, is what Ted

Cruz didn’t show.

Picking

an outlier for your start and/or end points isn’t the only way to

cherry-pick and hide the trend. Another is simply to pick a time span

that’s way too brief for the trend to make itself clear.

Fluctuations

can be large, especially for temperature data, and the trend can take

years to accumulate enough warming to overcome them. That’s one of

the reasons the typical time span to define climate instead

of weather is 30 years. If all you show is a brief

span of time, the trend doesn’t have long enough to “rise above

the noise.” But it’s still there.

The Global

Warming Policy Forum (GWPF) features a temperature graph in

their logo. The data are yearly average temperature according to the

Hadley Center/Climate Research Unit in the U.K. (HadCRU). Here’s

the HadCRU data itself:

The

year 2016 isn’t complete yet, but will be soon, so I’ve shown the

average for the year-so-far.

Here’s

the graph GWPF includes in their logo:

Notice

how it doesn’t start until 2001? Notice that it doesn’t include

2016’s year-so-far value? I wonder what they’ll do when 2016 is

complete and it’s harder to hide the temperature rise? Notice how

squeezed the data is into a small space, so the total

variation looks small? If they showed what came

before, or what came after, or even on a scale that helped see the

changes better, you might notice how clear the upward trend is.

There

are many ways to cherry-pick. Choose a time span selected to give the

wrong impression (start with 1997-1998); choose the one data set that

supports your claim but not any of the others; choose a single

event which bucks the trend (my grandmother smoked

cigarettes and lived to be 98 years old).

Climate

deniers use these tactics because they work. When they

suggest that the temperature data are a fraud, it raises your

suspicions. When they point out a “sudden drop” in temperature

data while concealing the trend, it can be persuasive. When you hear

that Arctic sea ice is no more extensive than it was on this date 24

years ago, it sounds convincing. When you see temperature data on a

graph starting in 1997-1998, it looks convincing.

Even

the best of us, even the smartest of us, are all too easily fooled by

misdirection (stage magicians can use that fact to make a very good

living). There’s no shame in being fooled by a charlatan, we’ve

all been taken in at one time or another. My hope is that now that

you’ve seen some of their tricks, when you run into them the next

time you’ll recognize them for what they are: tricks.

Fool

me once, shame on you. Fool me twice …

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.