Image

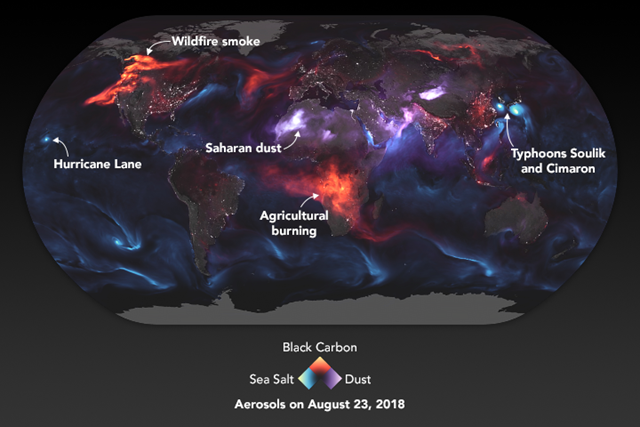

of the Day: Satellite view of black carbon from North America

wildfires and other aerosols, 23 August 2018

24

August, 2018

This

visualization highlights Goddard Earth Observing System Forward

Processing (GEOS FP) model output for aerosols on 23 August 2018. On

this day, huge plumes of smoke drifted over North America and Africa,

three different tropical cyclones churned in the Pacific Ocean, and

large clouds of dust blew over deserts in Africa and Asia. The storms

are visible within giant swirls of sea salt aerosol (blue), which

winds loft into the air as part of sea spray. Black carbon particles

(red) are among the particles emitted by fires; vehicle and factory

emissions are another common source. Particles the model classified

as dust are shown in purple. The visualization includes a layer of

night light data collected by the day-night band of the Visible

Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on Suomi NPP that shows the

locations of towns and cities. Graphic: Joshua Stevens / NASA Earth

Observatory

By

Adam Voiland

24

August 2018

(NASA)

– Take a deep breath. Even if the air looks clear, it is nearly

certain that you will inhale millions of solid particles and liquid

droplets. These ubiquitous specks of matter are known as aerosols,

and they can be found in the air over oceans, deserts, mountains,

forests, ice, and every ecosystem in between.

If

you have ever watched smoke billowing from a wildfire, ash erupting

from a volcano, or dust blowing in the wind, you have seen aerosols.

Satellites like Terra, Aqua, Aura, and Suomi NPP “see” them as

well, though they offer a completely different perspective from

hundreds of kilometers above Earth’s surface. A version of a NASA

model called the Goddard Earth Observing System Forward Processing

(GEOS FP) offers a similarly expansive view of the mishmash of

particles that dance and swirl through the atmosphere.

The

visualization above highlights GEOS FP model output for aerosols on

23 August 2018. On that day, huge plumes of smoke drifted over North

America and Africa, three different tropical cyclones churned in the

Pacific Ocean, and large clouds of dust blew over deserts in Africa

and Asia. The storms are visible within giant swirls of sea salt

aerosol (blue), which winds loft into the air as part of sea spray.

Black carbon particles (red) are among the particles emitted by

fires; vehicle and factory emissions are another common source.

Particles the model classified as dust are shown in purple. The

visualization includes a layer of night light data collected by the

day-night band of the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite

(VIIRS) on Suomi NPP that shows the locations of towns and cities.

Note:

the aerosol in the visualization is not a direct representation of

satellite data. The GEOS FP model, like all weather and climate

models, used mathematical equations that represent physical processes

to calculate what was happening in the atmosphere on 23 August 2018.

Measurements of physical properties, like temperature, moisture,

aerosols, and winds, are routinely folded into the model to better

simulate real-world conditions.

Some

of these inputs come from satellites; others come from data collected

by sensors on the ground. Fire radiative power data from the Moderate

Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) sensors on Aqua and

Terra is one type of satellite data that was assimilated directly

into the model. This type of data includes information about the

location and intensity of fires—something that the model uses to

help calculate the behavior of black carbon plumes.

Some

of the events that appear in the visualization were causing pretty

serious problems on the ground. On 23 August 2018, Hawaiians braced

for torrential rains and potentially serious floods and mudslides as

Hurricane Lane approached. Meanwhile, twin tropical cyclones—Soulik

and Cimaron—were on the verge of lashing South Korea and Japan. The

smoke plume over central Africa is a seasonal occurrence and mainly

the product of farmers lighting numerous small fires to maintain crop

and grazing lands. Most of the smoke over North America came from

large wildfires burning in Canada and the United

States.

Just

Another Day on Aerosol Earth

Video

shot near downtown Vancouver on Aug. 20 demonstrates the extreme haze

of smoke from hundreds of wildfires burning in British Columbia,

causing the mountains around the city to disappear from sight.

The

smoke coming from British Columbia’s forests amid a furious

wildfire season isn’t just reaching into Alberta.

Plumes

of smoke from the fires are believed to be travelling as far east as

Ontario, the Maritimes and beyond — even across the Atlantic Ocean

to Ireland.

That’s

according to David

Lyder, an air emissions

engineer with the Alberta government and one of the minds

behind FireSmoke.ca,

a website whose animated map shows the probable trajectory of

wildfire smoke within North America.

“Long-range transport of smoke from wildfires is not uncommon,” he told Global News.

Lyder

brought up one forecast in which smoke travelled from northern

Alberta and Saskatchewan, helping to trigger air quality advisories

in Washington, D.C.

And

it isn’t just B.C. that sends smoke so far.

“We

get smoke from Siberia,” Lyder said.

Modelling

of what wildfire smoke could look like on Aug. 25 at 8 p.m.FireSmoke.ca

The

map forms one component of the BlueSky

Western Canada Wildfire Smoke Forecasting System,

a project that first developed in 2007 out of concern about the need

for smoke projections to help inform weather forecasters, health

authorities and other parties.

BlueSky, a

software system that uses data to model fire, fuel consumption,

weather, emissions and dispersion, was initially developed by the

U.S. Forest Service.

Data

tracking all of these factors is pooled into a system that helps to

forecast concentrations of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) — an air

pollutant that can have negative effects on human health — from

wildfires for up to 48 hours.

Canada’s

BlueSky project uses the very same system, gathering data from

the Canadian

Wildland Fire Information System.

The

data helps to produce animations that display how PM2.5

concentrations will change over the next couple of days.

The

map showed some heavy smoke hitting Ontario and lesser plumes

travelling as far as Quebec and Labrador on Saturday; it had

previously shown smoke hitting the Maritimes.

This

animation shows heavy concentrations of smoke in Manitoba and Ontario

as well as a lesser concentration hitting Labrador on Aug. 25. FireSmoke.ca

The

people behind FireSmoke.ca are careful to note that the map shouldn’t

necessarily be relied upon in isolation; it’s considered

“experimental” and there are limitations.

Satellite

detections, for example, are used to find fires. If areas where fires

are burning are covered by clouds or smoke, then the emissions from

those blazes won’t be included in forecasts.

Projections

displayed by the map can be supplemented by looking at Canada’s

Wildfire Smoke Prediction System (FireWork),

which provides daily smoke forecasts.

The

massive Snowy Mountain wildfire in B.C.’s Similkameen region.

Joe

Lebeau / Hashmark Photography

Nevertheless,

both these modelling systems have shown smoke reaching as far as the

Maritimes.

FireWork,

for example, showed lighter PM2.5 concentrations hitting New

Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland this

weekend, though other fires are burning further east than B.C.

Projected

PM2.5 concentrations across Canada on Aug. 25.

FireWork

Fine

particulate matter is indeed reaching Eastern Canada, “but the

concentrations are much lower in the Maritimes than they are in

B.C.,” said Sarah Henderson, senior environmental health scientist

at the B.C. Centre for Disease Control.

There

are two components to wildfire smoke: PM2.5 and volatile organic

compounds (VOCs).

While

PM2.5 has been noted for its effects on human health, VOCs have more

to do with how smoke interacts with our senses.

“VOCs are the things that make our eyes sting and that give smoke that campfire smell,” Henderson said.

“They’re

not super risky, but they are irritating.”

VOCs

also dissipate as smoke travels.

“The

volatiles from the smoke are gone by the time they get to the east,”

Henderson said.

John

Clague, a professor of earth sciences at Simon Fraser University,

said satellite tracking of smoke has shown that heavy concentrations

of particles have been carried from B.C. and California to locations

thousands of kilometres to the east.

“I would say, however, that the duration of the exposure is limited,” he said.

While

the physical effects of smoke are less pronounced by the time it

travels such great distances, that doesn’t make it harmless.

Concentrations

may be lower, but the fine matter is still there.

“Wherever

it gets to, if smoke gets there, it carries with it some risk,”

said Henderson.

Still,

“we would expect that smoke from B.C. may have a small impact on

health in eastern parts of Canada, if and when it arrives there,”

she added.

BC

wilвfire service has been cutting supplies and people to fight for

several days. The community ran out of hoses and sprinklers during

the worst of the fire and only firefighters certified through BC

contractors were allowed in.. so people have stayed as the fires grew

and their plea for more help was answered. Now 2 dozen trucks with

supplies from Alberta are being told to leave

As

of 1215pm people gathered at save-on-foods

About

30 people are gathering near Overwaitea this morning

The

truckers from Alberta have now left Burns Lake. According to Burns

Lake councillor Charlie Rensby, the RCMP did not allow protesters to

stop the truckers from leaving, and the protest has now moved to

another location near the B.C. Wildfire Service base in Burns Lake.

Approximately

30 local residents are gathering near Overwaitea in Burns Lake this

morning trying to prevent over two dozen Alberta truckers from

leaving town.

The

Albertan truckers brought fire suppression equipment such as

sprinklers, pumps and hoses to Burns Lake to help combat the Babine

complex fire on the Southside. The group of fires is zero per cent

contained.

But

the B.C. Wildfire Service says this particular high-capacity water

delivery system isn’t going to work due to several factors,

including the terrain and an insufficient water source.

In

a statement Friday night, the fire service said the system requires

close proximity to “very large bodies of water” in order to work.

“They

also require relatively flat topography and are most effective in

densely populated areas,” it said.

Fire

crews are evaluating if the use of an alternate water delivery system

could work to suppress the blaze.

Burns

Lake councillor Charlie Rensby, who’s joining protesters this

morning, said he and others were not convinced by this explanation.

“The

biggest injustice is that politics is coming into play when we should

be saving people’s livelihoods,” said Rensby.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.