Polar Amplification vs a Godzilla El Nino — Is the Pacific Storm Track Being Shoved North by Arctic Warming?

27

January, 2016

It’s

an El Nino year. One of the top three strongest El Ninos on record.

The strongest by some NOAA measures. And we are certainly feeling its

effects all over the world. From severe droughts in Southeast Asia,

Africa, and South America, to Flooding in the Central and Eastern US,

Southern Brazil, and India, these impacts, this year and last, have

been extreme and wide-ranging. During recent days, Peru

and Chile saw enormous ocean waves and high tides swamping

coastlines.

Record flooding and wave height events for some regions. All impacts

related to both this powerful El Nino and the overall influence of

human-forced warming by more than 1 C above 1880s temperatures on the

whole of the hydrological cycle.

Amped

up by a global warming related 7 percent increase in atmospheric

water vapor (and a related increase in evaporation and precipitation

over the Earth’s surface), many of these El Nino related impacts

have followed a roughly expected pattern (you

can learn more about typical El Nino patterns and links to climate

change related forcings in this excellent video by Dr Kevin Trenberth

here).

However, so far, some of the predicted kinds of events you’d

typically see during a strong El Nino have not yet emerged. A

circumstance that may also be related to the ongoing human-forced

warming of the globe.

Storm

Track Not Making it Far Enough South

Particularly,

there has been an absence of powerful storms running in over Southern

California then surging on into Arizona, New Mexico and West Texas.

During strong El Nino events, heat and moisture bleeding off the

super-warmed Equator have typically fed powerful storms racing across

the Pacific. These storms have tended to engulf the entire US Pacific

Coast from San Diego through to Seattle. However, much of the storm

energy is often directed further south toward Central and Southern

California.

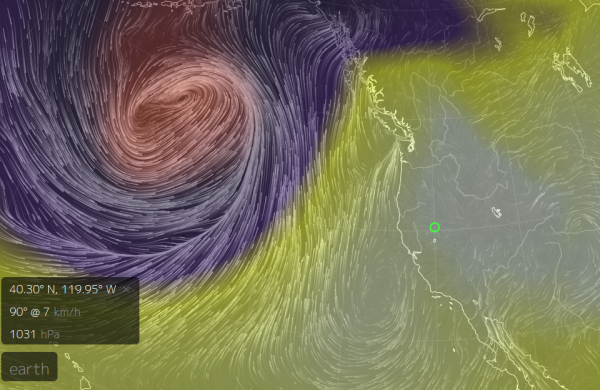

(A

massive Pacific storm being warded off by high pressure systems over

the US West Coast on Tuesday, January 26th. Image source: Earth

Nullschool.)

These

storms tend to run over regions that are typically much drier. So

strong El Ninos of the past have often generated abnormal and

memorable storms and rains. But this year there has been, mostly, an

abscense of such events. Storms have slammed into Northern

California, Oregon, been deflected back into the coasts of Canada and

Alaska, or even been bottled up near the Aleutian Island Chain.

But

today, a high pressure cell dominates the western US, warding off a

powerful storm system. The storm, howling just south of Alaska and

pushing out average 60 foot wave heights and hurricane force winds

across the Pacific, is predicted to rebound toward Alaska where it

will become bottled up in the Bering sea and push above freezing

temperatures into the Arctic Beaufort Sea during Winter. The storms

and rains will steer far away from Southern California and even much

of California altogether.

Rainfall

Patterns Have Tended Toward the North, Contrary to NOAA’s Seasonal

Predictions

(NOAA

precipitation quantities prediction for the coming week is indicative

a continued northward shift of the Pacific Storm track. Image

source: NOAA.)

It’s

a pattern more reminiscent of some strange ridiculously resilient

ridge (RRR) than that of a strong El Nino. And though storms later

this week are again predicted to slam into the Northwest and weekly

rainfall totals are expected to rise to near 1 inch for parts of

Southern California, the path of these storms and related moisture

flows are quite a bit further north than one would expect for a year

in which strong El Nino was the dominant feature.

The

moisture flow, instead, so far has tended northward across the upper

and central tiers of the US even as the El Nino related moisture

bleed toward the Gulf and East Coasts has remained quite intense.

Such observed weather is both contrary to what we’ve tended to know

about Strong El Nino and to NOAA’s seasonal forecasts which had

predicted much more rain for the southwest than what we’ve seen so

far.

(NOAA

three month outlook is more in line with traditional strong El Nino

forecasts bringing strong storms in through the southwestern US. We

currently do not see a prevalence of that particular pattern. Image

source: NOAA’s

Climate Prediction Center.)

Polar

Warming + Hot Blob Tugging the Storm Track Northward?

Since

weather patterns related to El Nino are an aspect of global

atmospheric dynamics — teleconnections between the influence of an

excess of hot air and heavy rainfall at the Equator and of large

scale atmospheric wave patterns downstream, you have to wonder if

there isn’t some kind of influence competing with El Nino on a

global scale. One with enough oomph to nudge the Pacific Storm Track

northward.

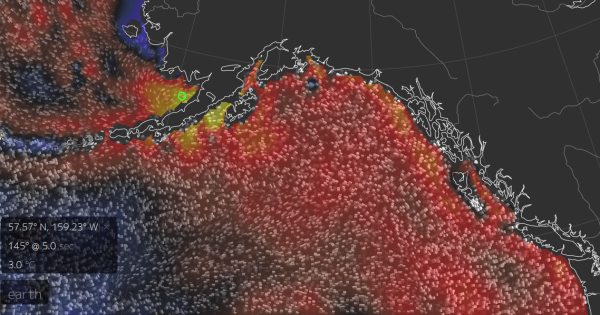

(The

Hot Blob is still a dominant feature of ocean waters in the Pacific

Northwest. Is its influence helping to pull the Pacific Storm Track

northward during a strong El Nino year? Image source: Earth

Nullschool.)

The

first likely suspect is the pool of still much warmer than normal sea

surface temperatures lurking off the US West Coast. Though somewhat

diminished from their peak during 2014 and 2015, the waters in the

hot blob off California, Oregon, Washington, Canada and Alaska are

still in the range of 1 to 3 C above average. A very large region of

significantly warmer than normal ocean surfaces that wasn’t present

during the 1982-83 and 1997-1998 super El Ninos. And much of the

warmest anomalies are now centered much further to the north along

the coast of Alaska.

But

the second potential player is likely even more significant. And that

would be an ongoing and extreme warming of the northern polar region.

Heating at the Pole generates less thermal gradient between the

higher Latitudes and the Equator. And such a lessened gradient would

tend to impact the strength of the circumpolar winds that drive

weather systems and storm tracks. In particular, the overall warming

of the globe would tend to pull these storm tracks northward even as

the loss of thermal gradient would tend to enhance wave patterns in

the Jet Stream.

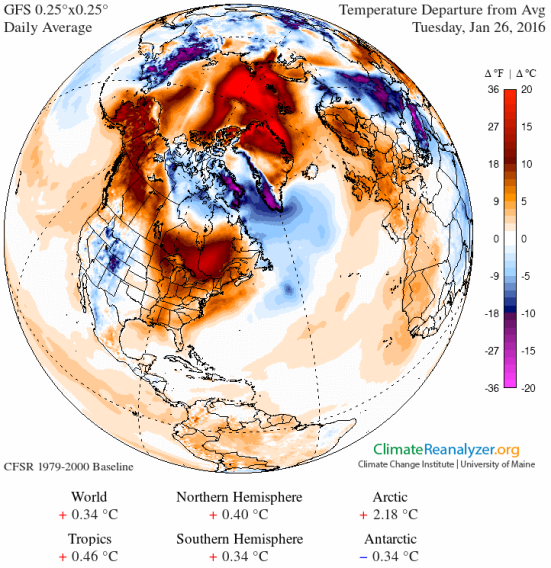

(Polar

Amplification shown as very intense in the January 26 Climate

Reanalyzer graphic. Is Polar Amplification helping to shove the

Pacific Storm Track northward even during a record strong El Nino

year? If so, it’s bad news for long term moisture levels in the US

Southwest. Image source: Climate

Reanalyzer.)

Perhaps

also specifically related to this ongoing polar amplification, we

find that two warm slots — one over the Barents and far North

Atlantic east of Greenland and another over the Bering — have

tended to develop during recent Winter years. These slots have often

served as staging areas for warm air invasions of the Arctic. But

what they also represent are regions of water that have been freshly

liberated from their sea ice coverings. As such, these vast regions

of water serve as heat transport and ventilation zones. And all this

extra heat energy may be sucking the related North Atlantic and North

Pacific Storm tracks into what may well be described as an oceanic

and atmospheric trap.

If

such a situation where the case, we’d tend to see a dipole of warm

east, cold west in the storm trap regions. And that’s exactly what

we’ve seen more and more of with Greenland and Siberia serving as

the backdrops to reinforce this tendency. Thus setting up the stage

for cold air slots cutting through Northeast Siberia and Northeast

Canada and warm, wet air slots over Alaska and the UK.

The

question to be asked is, then, are these new influences related to

human-forced warming also now doing battle with El Nino for control

over the Pacific Storm Track? And has that influence increased enough

to dramatically nudge that track northward? We may find the answer to

that question in what happens to the direction of powerful Pacific

Storms over the next few months. But early indications seem to be

that polar warming and the related hot blob may have thrown a wrench

in the kinds of El Nino storms that we’ve been used to.

Links:

Hat

Tip to Colorado Bob

Hat

Tip to DT Lange

Hat

Tip to Andy in San Diego

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.