Puerto Rico Is Burning Its Dead, And We May Never Know How Many People The Hurricane Really Killed

People whose bodies are cremated are largely not being counted in the official death toll.

28

October, 2017

AGUADILLA,

Puerto Rico — Funeral directors and crematoriums are being

permitted by the Puerto Rican government to burn the bodies of people

who died as a result of Hurricane Maria — without those people

being counted in the official death toll.

The

result is a massive loophole likely suppressing the official death

count, which has become a major indicator of how the federal

government’s relief efforts are going because President Trump

himself made it one.

During

Trump’s photo-op visit to the US territory — whose residents are

US citizens — three weeks ago, he boasted that the death toll was

just 16. It doubled by the time he returned to Washington that same

day. The death toll is now at 51, a figure widely contradicted by

what funeral homes, crematoriums, and hospitals on the ground tell

BuzzFeed News.

Then,

last week, when asked how he would rate the White House’s response

to the crisis, Trump said, "I’d say it was a 10.” More than

a month after the storm made landfall on Sept. 20, 2.6 million people

are without power, at least 875,000 people don’t have access to

running water, and 66% of the island still doesn’t have cell

service.

Trump

added, “I’d say it was probably the most difficult when you talk

about relief, when you talk about search, when you talk about all of

the different levels, and even when you talk about lives saved.”

Meanwhile, two US representatives and 13 senators recently wrote

letters to the acting head of homeland security requesting

investigations into the death toll.

Last

week, BuzzFeed News visited 10 funeral homes and crematoriums in two

Puerto Rican municipalities on the territory’s western coast,

Aguadilla and Mayagüez, at least two hours away from the bustling

San Juan. The findings include:

Communication

between the central institute certifying official hurricane deaths,

called the Institute of Forensic Sciences, and funeral homes or

crematoriums appears to be fully broken, with each side waiting for

the other to take action.

The

central institute is also giving crematoriums permission to burn

bodies of potential hurricane victims — which is happening more

because it is cheaper and logistically easier as families rebuild

their lives — without examining them first, which means they are

not being counted in the official death toll.

Disaster

experts say this lack of a transparent and consistent approach to

counting deaths means the toll is likely inaccurate.

And

experts also say an inaccurate official death toll potentially cheats

families out of FEMA relief funds and could hurt how future disasters

are handled.

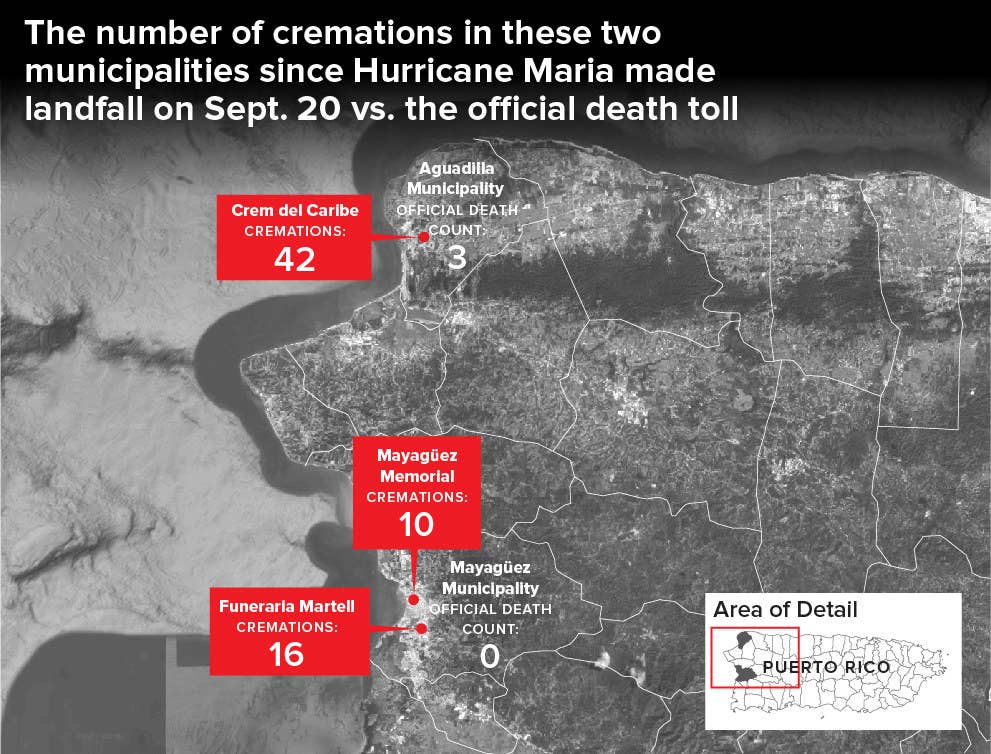

The

funeral home and crematorium directors told BuzzFeed News that they

had received dozens of bodies of people who died of hurricane-related

causes — just the cases from these two municipalities would

potentially more than double the death toll if they were included.

The Forensic Institute permitted the bodies of at least 42 potential

hurricane victims to be burned, according to one crematorium

director.

Puerto

Rico’s safety department says the funeral and crematorium directors

should send any potential hurricane-related victims to the institute

before they’re burned — but admit they haven’t actually

officially communicated that to them.

John

Mutter, a professor of earth sciences and public affairs at Columbia

University who studied how the death count was handled after

Hurricane Katrina, said Puerto Rico’s procedures seem to be

“deliberately trying to keep the numbers low,” which he called

“unconscionable.” Other experts called it a failure of

bureaucracy.

The

White House and the office of the Governor of Puerto Rico, Ricardo

Rosselló, didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Asked

directly if the number of hurricane-related deaths in Puerto Rico is

being undercounted, a spokesperson for the Puerto Rico Department of

Public Safety dodged, saying, “We can’t infer or reach any

assumptions or inferences. If there really are cases like this, they

have to present them to the authorities.”

But,

at this point, many of those bodies have been burned to ash.

“I never expected all of this”

In

Aguadilla, a municipality of around 60,000, the official

death toll currently counts three fatalities from the hurricane: one

person who drowned in flooding, one person who fell off his roof

while trying to repair hurricane damage, and one person who died of

a bone infection.

But

staff at the only crematorium in the municipality, Crem del Caribe,

said they were given permission by the forensic institute to cremate

at least 42 bodies of other people who had died as a result of the

hurricane. That included people who died due to a lack of oxygen

supply, failure of dialysis and oxygen machines because of the lack

of electricity, and people who died of heart attacks. (Seventy-five

percent of the island still has no power, and questions

are being raised about

the firm contracted to fix it.)

“A

lot of people have died as an indirect result of the hurricane,”

said Jaime Domenech, crematorium director at Crem del Caribe.

“Especially older people, who because of their health conditions

many of them depended on electricity.”

The

majority of those cases came from funeral homes in the area, like

Vitin Alvarez, 68, who died a week after the hurricane made

landfall.

Alvarez

had Alzheimer’s disease, and his death certificate states his

primary cause of death was respiratory failure. His wife, Blanca

Alvarez, 63, told BuzzFeed News he died because she couldn’t get

gasoline to power the generator he needed for his oxygen machine.

There’s no mention of the lack of electricity on his certificate.

“It’s

so difficult to get gasoline. And there wasn’t a way to

communicate with anyone,” Alvarez told BuzzFeed News outside her

home in Aguadilla.

Alvarez

cremated her husband because of financial concerns and because she

was overwhelmed handling basic things like finding food and water

after the hurricane. He was the first person in the Alvarez family

ever to be cremated instead of buried.

“We

were always together. I’m still trying to adjust to life without

him,” said Alvarez. “I never expected all of this to be

happening at the same time.”

Several

funeral directors told BuzzFeed News they’re seeing an increase in

cremations over burials after the hurricane, in part because it’s

less expensive and requires less planning as people rebuild. They

had already seen an uptick in the number of cremations as a result

of the financial crisis in Puerto Rico, they said, but said the

numbers have increased even more in Maria’s aftermath.

The

cremation cost Alvarez $1,300, she said. One funeral home director

said burial services cost between $4,000 and $12,000 in Aguadilla.

She

said her husband had life insurance but she’s still waiting for

the payout. Alvarez wasn’t aware that FEMA has

a disaster funeral assistance program “to

help with the cost of unexpected and uninsured expenses associated

with the death of an immediate family member when attributed to an

event that is declared to be a major disaster or emergency.” FEMA

did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

A confusing process

The

Puerto Rican government has said that the island’s

Institute of Forensic Sciences, in San Juan, must examine and

certify the bodies of any hurricane-related deaths before they are

counted in the official death toll. When the region isn’t dealing

with a disaster, the bodies of people who killed themselves,

suffered a suspicious death, or were possible victims of a crime are

sent to the institute for investigation.

The

spokesperson for the Puerto Rico Department of Public Safety,

Karixia Ortiz Serrano, acting as spokesperson for the institute,

told BuzzFeed News that the institute does not have guidelines for

which hurricane-related deaths to add to the official death toll and

which to keep off, and said they’re making decisions on a

“case-by-case” basis.

“There

are no specific categories, but they look at the situation,”

interview family members, “analyze it, and come to their decision

— and everything has to be scientifically-based,” she said.

Here’s

where things go awry.

The

public safety department says it’s the responsibility of funeral

homes, crematoriums, and hospitals to notify and send or bring

bodies to the forensic institute if they’re possible

hurricane-related deaths.

But

all 10 funeral homes and crematorium directors BuzzFeed News spoke

to said they haven’t received any specific guidance on what

they’re supposed to do with the bodies of people who died as a

result of the hurricane. Ortiz confirmed to BuzzFeed News that no

official guidance was sent to funeral homes and crematoriums, many

of which take in bodies that don’t need to go to the hospital

first.

Ortiz

says the directors of the facilities should know better. “They

know that the place that they do all the scientific investigations

is at the institute,” she said. “The funeral homes are in

constant communication with the institute because they’re the ones

that bring the bodies and take them back.”

Still,

cremating a body requires written approval from the forensic

institute — which has the option to ask for the bodies to be sent

to San Juan for examination before they’re burned. But the funeral

and crematorium directors who spoke to BuzzFeed News said the

institute has given them permission to cremate dozens of bodies of

people who died of hurricane-related causes, and were not asked to

send them to the institute.

Asked

specifically about this, Ortiz reiterated it’s on crematoriums and

funeral homes to communicate with the forensic institute if they

think a death should be examined for inclusion on the death toll.

“We

have heard,” that possible hurricane victims were being cremated

without examination, Ortiz said. “We aren’t saying that they’re

totally true or totally false. But what we are saying is, if you

have a case like that, send us all the information to be able to

look at it” before cremation.

“Natural causes”

Many

funeral directors have conflicting definitions of what counts as a

hurricane-related death and what doesn’t.

Some

funeral directors classified cardiac and respiratory failure after

the hurricane as death by “natural causes” only. Others said

they consider those hurricane-related because they happened as a

result of the conditions created by the Maria: a lack of food,

water, electricity, and fuel. (The official death toll does include

people who had heart attacks, took their own life, and who died for

lack of oxygen and electricity for dialysis machines.)

Experts

said this goes back to a lack of guidance from the public safety

department.

“If

you wanted to make the count as small as possible that’s the way

to go about it,” Mutter, the Columbia professor, said about lack

of uniform procedure and communication about certifying

hurricane-related deaths. “Because somebody’s sitting there

saying, this is a disaster death, this one is not.”

Mutter

said that based on Puerto Rico’s poverty level and the strength of

the storm, he would have expected the death toll to be in the

hundreds by now.

“In

fact there’s a lot of deaths that come from the exacerbation of

preexisting conditions by the trauma of the disaster event. And they

are normally counted. They ended up being counted in Katrina. They

are considered disaster deaths. If you take them out you get a small

number,” he said.

A

review of the funeral homes and crematoriums BuzzFeed News visited

shows the discrepancies.

Monica

Rodriguez, of Funeraria Soto Rodriguez, said her funeral home has

received six bodies since the hurricane. Of those, four came from

senior homes — their death certificates say they died of cardiac

arrests. Another was a quadriplegic man who died of an infection

after arriving at a hospital too late to be treated effectively, and

another was a dialysis patient who died in their home when their

machine failed. Two of the six were cremated, Rodriguez said.

Here’s

her definition of a hurricane-related death: “You can’t exactly

say these people died because of the hurricane, because they were

old people or they already had health conditions,” she said,

adding that in general, death certificates don’t necessarily

account for the conditions in which someone died.

But

she also said she believed the conditions created by the hurricane

lead to these deaths.

“I

can tell you that we had four deaths of elderly people who were in

senior homes. They didn’t have air-conditioning. It’s possible

they didn’t have enough oxygen. I’m telling you about the

conditions that were caused by the hurricane, not causes of death as

they’re written” by doctors on death certificates, Rodriguez

said.

At

the Javariz funeral home in Aguadilla, 19 bodies have come in since

the hurricane. Of those, most died during the hurricane or because

of conditions created by the hurricane, said director Tomas Javariz.

Thirteen were cremated.

Javariz

considers two who died by suicide, five due to a lack of oxygen, one

from an organ failure, and 11 attributed to cardiac or respiratory

arrest as hurricane-related deaths.

He

sent the two who died by suicide to the forensic institute —

standard practice for suicide cases — but he said he didn’t send

the others because the institute never asked for hurricane-related

deaths. The institute gave him permission to cremate them.

Another

funeral home in Aguadilla, Funeraria San Antonio, received six

bodies since the hurricane. Those included one of the three counted

in Aguadilla’s official death toll — a man who fell off his roof

while trying to repair it — whose body was examined by the

forensic institute in San Juan. Another died of cancer and the rest

died of “natural causes,” an employee at the funeral home said,

which included cardiac and respiratory arrests.

Funeraria

Hernandez-Rivera, the fourth funeral home in the region, received 15

bodies since the hurricane, including five or six heart attacks,

according to funeral director Raul Hernandez-Rivera. He also said

that he didn’t believe those cases could be counted as

hurricane-related because they didn’t involve people drowning or

dying while trying to repair hurricane damage.

The

institute gave him permission to cremate 8 of the 15 bodies. He sent

one to the institute — the body of a woman who was bedridden and

drowned during the hurricane — and she is counted in the official

death toll.

In

the nearby municipality of Mayagüez, there were no

hurricane-related deaths, according to the official toll. That’s

at odds with the number of cases received by local funeral homes.

Funeraria

Fernandez received 13 bodies since the hurricane. They said at least

six of those people died because of a lack of oxygen supply, and one

died because of a dialysis machine not working, in addition to

several heart attacks. Nine of those were cremated. Five were sent

to the forensic institute for examination. None have been included

in the death toll.

Another,

Mayagüez Memorial, received 42 bodies since the hurricane, 10 of

which were cremated with the forensic institute’s permission

without an examination, according to a staff member there.

“There

were some that had to be the result of the hurricane,” said the

staff member, who asked not to be named.

Funeraria

Martell received 39 bodies since the hurricane — 16 were cremated

with permission from the institute without examination.

“I

would say that almost all of them were [related to the

hurricane],”said Germarie Hernandez, the funeral director. She

said she received 10 cases from Hospital Perrea and three from the

Centro Medico Mayagüez, all from the intensive care units. The

other 26 cases came from private homes or senior homes.

“That is a failure of government”

The

lack of guidelines for creating an official death toll is a

recurring problem after large-scale disasters in the US, according

to experts, who say there is no federal standard because local

coroners and governments have jurisdiction over counting and

certifying deaths.

After

Hurricane Katrina, FEMA organized

teams of mortuary experts through

the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) — known as

Disaster Mortuary Operational Response Teams or DMORT — to assist

the state of Louisiana in counting storm-related deaths. (Puerto

Rico’s safety department said they have 40 DMORT personnel

assisting the Institute of Forensic Sciences in San Juan.)

During

Katrina, FEMA also contracted Kenyon International, a private

company that specializes in recovering and identifying remains after

disasters. The company has not been contacted by federal agencies or

the Puerto Rican government for relief on the island, they told

BuzzFeed News. FEMA did not respond to a request for comment.

“One

of the things I advise governments to do is … come up with and put

out guidance on what is the time period, the definition, the cause,

manner, and mechanism [for counting deaths],” said Robert Jensen,

CEO of Kenyon International, which also assisted authorities after

9/11, the Oklahoma City bombing, and the Grenfell Tower fire in

London.

He

said instructions should be clear for funeral homes on what the

actions and reporting requirements are in cases like Maria.

“What

we want to be able to do is clearly identify what was the human cost

in this event and make it easier,” he said. “In the absences of

leadership or guidance, people are going to take action. The dead

can’t just sit.”

He

said the current lack of transparency and communication with those

handling burials and cremations across the island means the count is

less likely to be accurate.

“That

is a failure of government. That is part of the responsibility,”

he said, adding that having accurate death toll data can be used to

help governments prepare better for future disasters. For example,

“We have one generator— it needs to go to location A and not

location B.”

“Short

of having really clear guidance issued then you leave the decision

up to each individual funeral director, doctor,” he said. “I’d

love to say that it’s an intentional cover-up but it’s just

bureaucracy at its worst.”

The

forensic institute has heard from some funeral directors who said

they had cases of hurricane deaths that had not been examined by the

institute before burial or cremation, Ortiz said.

“There

were a few situations like this, and when [the director of the

forensic institute] asked for information and specific data, and

when she looked at the cases … it turned out that they were just

rumors, or that they couldn’t be substantiated.”

Ortiz

could not provide details about how many funeral directors had

raised such concerns with the institute, or the details about the

investigations that lead the institute to believe that they were

“just rumors.” But the institute is open to investigating any

case that’s specifically brought to them, she said.

“If

it’s a rumor they don’t register them,” she said.

Jensen

said the Puerto Rican government’s process is not consistent with

a scientific approach.

“Scientifically

based is great but the thing about science is it has to be repeated

given the same conditions and everyone has to be able to repeat it

given the same parameters,” he said.

Puerto

Rico Governor Ricardo Rossello said three weeks ago that he had

conducted a survey of the island’s hospitals and medical centers to

update the death toll. The Department of Public Safety, when asked

about the survey, said they will do them “periodically” but

couldn’t say when. They said the government is in contact with

hospitals but that there are communication difficulties that make it

hard to do another survey.

Jensen

said that after six months or a year, families will begin to think

about the deaths of their loved ones in the context of this crisis —

and whether they could have been eligible for more financial support

through insurance policies if their loved ones’ deaths had been

classified differently. One clear area they could have lost

financial resources, he said, was in receiving federal grants

through FEMA to assist with emergency funeral costs.

“Here’s

where it has an impact. It has an impact for different insurance

policies, it has an impact on families,” he said, adding that in

at least one other large-scale disaster Kenyon has worked on,

families hired forensic experts months later to determine whether

they had a legal case that first responders were at fault in their

family members’ deaths.

“In

a national disaster you’re one of however many and everyone is

focused on food, water, life support,” he said, “and that makes

it just a little bit harder for the families of the dead because it

feels like their life didn’t matter.” ●

CORRECTION

Karixia

Ortiz Serrano, who is acting as the spokeswoman for the Institute of

Forensic Sciences, works at the Puerto Rico Department of Public

Safety. An earlier version of this article said she worked for the

Puerto Rico Department of Public Health.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.