“The

1890s extent of ice volume in New Zealand’s Southern Alps was 170

km3, compared to 36.1 km3 now. That disappearance of 75-80% of

Southern Alps ice is graphic evidence of the local effects of global

warming”

It is a matter of shame that there has been so little in New Zealand media (count on the fingers of ONE hand) on the demise of ice in the Southern Alps in New Zealand and the rapid retreat of our main glaciers.

About a week ago Radio NZ featured the following interview with Dave Bamford, a lifelong mountain climber. It was unscheduled and labelled by "Nghts Sport" (there are no details as to what is being discussed in the interview, and yet it gave one of the best first-person accounts of what is happening to our Alps.

Judging from what Dave is saying it would be hard to find a climate sceptic amongst the climbing fraternity because they have to live with the consequences.

Already many places have become unaccessible and passes over the mountains are in essence closed because of the danger of landslides from the collapse of the morraine wall on the sides of the ice river.

Listen to the interview. It is worth your time.

Mountaineer, Dave Bamford , describes the rapid retreat of New Zealand's glaciers

Listen to the interview here.

You can see 2 years of glacier retreat illiustrated here.

It is a matter of considerable shame that I have to report that some of the main reporting on this has been in the foreign media.

This piece of research was carried by Australia's the Conversation and not by New Zealand media.

The largely bare Southern Alps at the end of summer, 2018.

A

third of the permanent snow and ice of New Zealand’s Southern Alps

has now disappeared, according to our new research based on National

Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research aerial

surveys.

A

NASA satellite photo of the Southern Alps, stretching along New

Zealand’s South Island, shown here capped with snow in

2002. Jacques

Descloitres/NASA/Wikimedia Commons

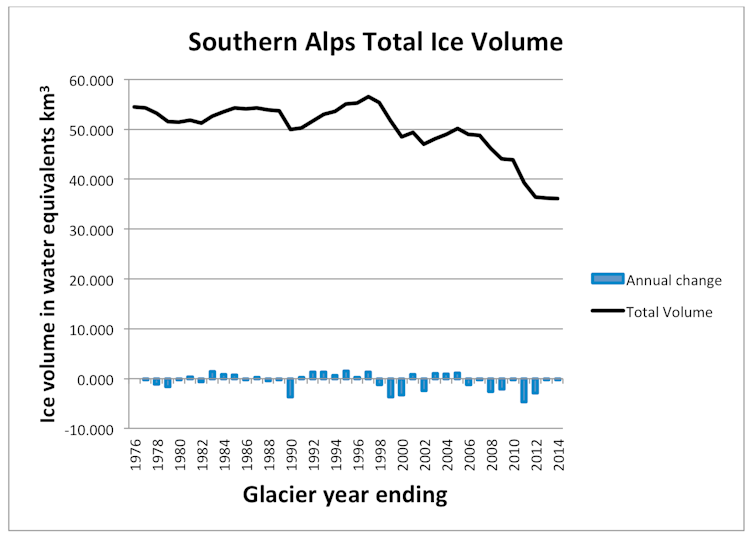

Since

1977, the Southern Alps’ ice volume has shrunk by 18.4 km3 or

34%, and those ice losses have been accelerating rapidly in the past

15 years.

The

story of the Southern Alps’s disappearing ice has been very

dramatic – and when lined up with rapid glacier retreats in many

parts of the world, raises serious questions about future sea level

rise and coastal climate impacts.

The

Southern Alps’ total ice volume (solid line) and annual gains or

losses (bars) from 1976 to 2014 in km3 of water equivalent, as

calculated from the end-of-summer-snowline monitoring programme.

Glaciers are large-scale, highly

sensitive climate instruments, which in an ideal world we would pick

up and weigh once a year, because their fluctuations provide one of

the clearest signals of climate change. A glacier is simply the

surplus ice that collects above the permanent snowline where the

losses to summer melting are less than the gains from winter

accumulation. A glacier flows downhill and crosses the permanent

snowline from the area of snow gain to the zone of ice loss. The

altitude of this permanent snowline is the equilibrium line: it marks

the altitude at which snow gain (accumulation) is exactly balanced by

melt (ablation) and is represented by the end-of-summer snowline.

<image id= Authors, CC

BY

In

1977, one of us (Trevor Chinn) commenced aerial photography to

measure the annual end-of-summer snowline for 50 index glaciers

throughout the Southern Alps.

These

annual end-of-summer surveys have been continued

by the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA).

We then use the NIWA results to calculate the annual glacier mass

balance and hence volume changes of small to medium sized glaciers in

the Southern Alps. Small to medium glaciers respond quickly to annual

variability of weather and climate, and are in balance with the

current climate.

Not

so the twelve largest glaciers: the Tasman, Godley, Murchison,

Classen, Mueller, Hooker, Ramsay, Volta/Therma, La Perouse, Balfour,

Grey, and Maud glaciers. These have a thick layer of insulating rocks

on top of the ice lower down the glaciers trunk. Their response to

new snow at the top is subdued, and take many decades to respond.

Up

until the 1970s, their surfaces lowered like sinking lids maintaining

their original areas. Thereafter, glacial lakes have formed and they

have undergone rapid retreat and ice loss.

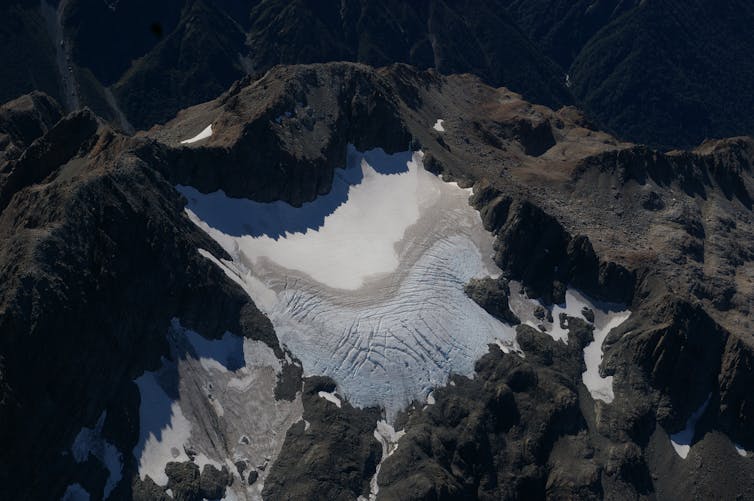

The

Rolleston index glacier in the Southern Alps of New Zealand, showing

the accumulation area where fresh clean snow gain occurs above the

end-of-summer snowline, and the area of melting ice below. Here, a

negative balance year in 2009 shows a higher end-of-summer snowline

revealing underlying old snow. Trevor

Chinn, CC

BY

To

come up with our calculations, we have used the snowline survey data

plus earlier topographic maps and a GPS survey of the ice levels of

the largest glaciers to calculate total ice-volume changes for the

Southern Alps up until 2014.

Over

that time, ice volume had decreased 34%, from 54.5 km3 to

36.1 km3 in water

equivalents. Of that reduction, 40% was from the 12 largest glaciers,

and 60% from the small- to medium-sized glaciers.

These

New Zealand results mirror trends from mountain glaciers globally.

From 1961 to 2005, the thickness of “small” glaciers worldwide

decreased approximately 12 metres, the equivalent of more than 9,000

km3 of water.

Global

Glacier Thickness Change: This shows average annual and cumulative

glacier thickness change of mountain glaciers of the world, measured

in vertical metres, for the period 1961 to 2005. Mark

Dyurgerov, Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of

Colorado, Boulder, CC

BY

Martin

Hoelzle and associates at the

World Glacier Monitoring Service have estimatedestimate

the 1890s extent of ice volume in New Zealand’s Southern Alps was

170 km3,

compared to 36.1 km3 now.

That disappearance of 75-80% of Southern Alps ice is graphic evidence

of the local effects of global warming.

Further

large losses of ice in the Southern Alps have been projected by

glaciologists Valentina Radic and Regine Hock, suggesting that only

7-12 km3 will

remain by the end of the 21st century. This is based on regional

warming projections of 1.5°C to 2.5°C. This represents a likely

devastation of ice cover of the Southern Alps over two centuries

because of global warming.

And

where does all this melted glacier ice go? Into the oceans, thus

making an important contribution to sea level rise, which poses a

serious risk to low-lying islands in the Pacific, and low-lying

coastal cities from Miami in the US to Christchurch in NZ.

In

2013, the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimated mountain

glacier melt has contributed about 6 to 7 centimetres of sea level

rise since 1900, and project a further 10 to 20 cm from this source

by 2100.

This excellent piece camed from the New York Times

But

a local tour operator, Fox Glacier Guiding, has been unable to take

tourists onto the ice on foot since April, when glacial retreat

caused a river to change course, blocking access to a popular hiking

trail. And at another glacier about 14 miles down the road, the

operator Franz Josef Glacier Guides lost hiking access in 2012, also

because of retreating ice.

Now,

air landings by helicopter are the only way to set foot on the

glaciers, which lie at the confluence of the Southern Alps and the

Tasman Sea on the west coast of New

Zealand’s

South Island. As a result, both companies have made helicopter tours

their primary product, increasing business for local

helicopter operator.

Finally, earlier this year the gap was filled by this article in stuff.co.nz

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.