Abnormal Antarctic Heat, Surface Melt, Giant Cracks in Ice Shelves — More Troubling Signs of a World Tipping Toward Climate Chaos

23

January, 2017

Around its edge zone, and from glacier top to ice shelf bottom, Antarctica is melting. Above-freezing surface temperatures during the austral summer of 2016-2017 have resulted in the formation of numerous surface-melt ponds around the Antarctic perimeter. Large cracks grow through Antarctic ice shelves as warmer ocean currents melt the towering glaciers from below. The overall picture is of a critical frozen region undergoing rapid change due to the human-forced heating of our world — a warming that has brought Antarctica to a tipping point, for such fundamental alterations to Antarctic ice are now likely to bring about a quickening rate of sea-level rise the world over.

Surface

Melt Visible From Satellite

During

2016-2017, Antarctic surface temperatures ranged between 0.5 and 1

degree Celsius above

the already warmer-than-normal 1979 to 2000 average for

most of Southern Hemisphere summer. While these departures for this

enormous frozen continent may not sound like much at face value,

they’ve translated into periods of local temperatures up to 20 C

above average. As a result, measures around Antarctica along and near

the coastal zone have risen above the freezing mark on numerous

occasions. These periods of much-warmer-than-normal weather have in

turn precipitated widespread episodes of surface melt.

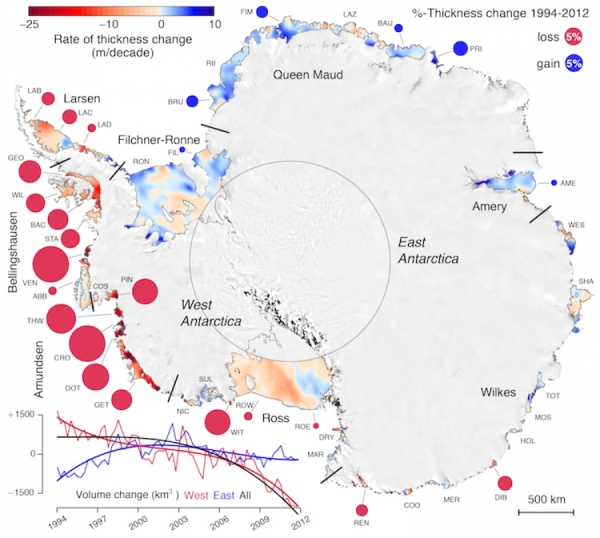

(This

Antarctic volume-change melt map, which tracks thinning along various

coastal ice shelves from 1994-2012, provides a good geographical

reference for ice shelves experiencing surface melt or severe

rifting. The Amery Ice Shelf [AME], King Baudouin Ice Shelf [BAU],

and the Lazarev Ice Shelf [LAZ], stable through 2012, all showed

extensive surface melt this summer. Meanwhile the Larsen C Ice Shelf

[LAC] and Brunt Ice Shelf [BRU] both feature large rifts that

threaten destabilization. Image source: Volume

Loss from Antarctica’s Ice Shelves is Accelerating/Sciencemag.org.)

This

year, one region in particular has seen temperatures hitting above 0

C consistently: the valley into which the Lambert, Mellor, and Fisher

glaciers flow into the Amery

Ice Shelf.

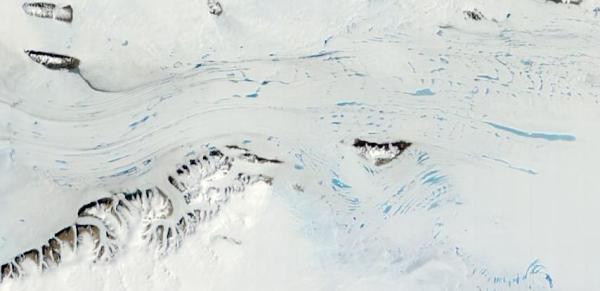

There, warming has resulted in the formation of multiple large

surface-melt ponds. The below image is a January 22nd NASA satellite

shot of an approximate 100-by-40-mile section of this glacial outflow

zone. The blue areas are melt ponds, some as large as 3 miles

wide and 20 miles long.

The

Amery Ice Shelf is one of East Antarctica’s largest. Like many of

Antarctica’s ice shelves, Amery is melting, with about

46 billion tons of ice lost from this shelf alone each year.

As with other Antarctic ice shelves, Amery’s melt is

mostly below the

surface, caused by warming ocean waters. However, in recent

years, considerable surface melt on Amery’s feeder glaciers

likely also contributed to significant volume losses in the self.

(Large

melt ponds up to 20 miles long cover glaciers flowing into the Amery

Ice Shelf on January 22, 2017. Image source: LANCE

MODIS.)

Surface

melt for Amery has become an increasingly prevalent feature since

2013, with 2017 melt for January 22 the most widespread for any of

the past five years in this region. East Antarctica rarely saw large

surface melt events prior to the 2000s, and this year’s warming and

large melt ponds are a considerable feature. While basal warming is

often the cause of the greatest mass losses, surface melt can act

like a giant wedge driven into ice shelves, helping to break them up.

Melt wedging in glaciers can also increase their forward rate of

movement as heat content rises and as the points at which glaciers

contact the ground become lubricated.

Moving

north toward Dronning Maud Land along the East Antarctic coast, we

find another region of surface melt ponding on the King

Baudouin Ice Shelf.

Nearly as widespread and extensive as the melt on the Amery

Shelf’s glaciers, the King Baudouin melt is no less impressive and

concerning.

(King

Baudouin Ice Shelf shows extensive melt ponding along a 40-mile swath

of its southwestern corner in January 2017. Image source: LANCE

MODIS.)

The

largest melt zone shows nearly continuous ponding along a

40-mile-wide diagonal near the ice shelf’s southwestern contact

point with East Antarctica’s mainland. A smaller section of melt

appears as light blue splotches about 60 miles to the west of the

larger melt zone in the image above (for reference, bottom edge of

frame represents about 250 miles).

Unlike

glacial surface ponding near Amery, melt on King Baudouin occurs

directly over the floating ice shelf. This form of melt adds greater

stresses as the heavy pools of water can act as wedges that drive

gaps in the ice apart. Past instances of widespread surface ponding

have occurred in conjunction with the rapid break-up of Larsen ice

shelves along the Antarctic Peninsula. Taking a look at past years in

the satellite record, we find that this region of King Baudouin has

been susceptible to melt since at least 2013. However, the extent of

2017 melt is the greatest in the record for this time of year.

The

next ice shelf to the west of King Baudouin, the

Lazarev Ice Shelf, shows

extensive melt along what appear to be various rifting features

streaming out from an open ocean gap where the ice shelf contacts

land:

(Ten-mile-long

melt ponds visible on the surface of the Lazarev Ice Shelf. Image

source:LANCE

MODIS.)

Over

recent years, the ocean gap — visible as a dark section in

center-bottom frame of the image above — has slowly grown larger.

There, open ocean water has gradually taken up a larger and larger

section of Lazarev’s land-contact point. Meanwhile, from 2013

to 2017, melt ponds have tended to radiate out from this open

gap region along rifts in the ice shelf structure during summer as

air temperatures have risen above freezing.

This

year, melt appears to be quite extensive with two parallel

10-mile-long melt ponds filling in rift features with many smaller

melt ponds interspersed. The open ocean gap combined with rifts

filling with what is now seasonal melt water gives the overall

impression of a rather weak structure.

Ice

Shelves Cracking Up

Though

regions on or near the Amery, King Baudouin and Lazarev Ice Shelves

show the most obvious surface melt features, large melt ponds also

formed near the Fimbul Ice Shelf. Ponds also formed during

a Föhn wind event near

the Drygalski

Ice Tongue.

Even as such instances of surface melt became a more obvious feature

across Antarctica, at least two large ice shelves were run through by

growing rifts that threatened their stability.

One

such rapidly-expanding rift forced the British Halley VI research

team to evacuate their base of operations on the floating Brunt Ice

Shelf. This rift, which had until late 2016 been growing only

gradually, doubled in length in less than three months. Its

gaping chasm threatened to cut the expedition off from the Antarctic

mainland and set it adrift at sea —forcing

an early evacuation as a precaution.

(Drone

footage of Brunt Ice Shelf’s rapidly growing crack. From October

through early January, the crack doubled in size from 22 kilometers

in length to 44 kilometers. Video source: Antarctic

Survey.)

Meanwhile, a

large crack that will soon result in a 2,000-square-mile iceberg

breaking from the Larsen C Ice Shelf recently grew by another

six miles to 100 miles long.

The Connecticut-sized ice chunk now only hangs by a 15 to 20 mile

thread. With the loss of this very large segment of ice, researchers

are concerned that Larsen C may destabilize and ultimately succumb to

the fate of Larsen A and Larsen B — breaking into thousands of

separate icebergs and floating away into the Southern Ocean.

Signs

of Melt, Destabilization as More Above-Freezing Temperatures are on

the Way

With

so many large melt ponds and melt-related rifts forming in

Antarctica’s ice shelves, it’s worth considering that these

shelves serve as a kind of door jam holding large glaciers back from

flooding into the ocean. And as more ice shelves melt and

destabilize, the faster these glaciers will move and the faster the

world’s oceans will rise.

So

much widespread melt and rifting of Antarctica’s ice shelves is a

clear warning sign. And if enough of the ice shelves go, then rates

of sea-level rise could hit multiple meters this century.

(Many

locations along the coast of Antarctica will see 5-15 C above-average

surface temperatures this week, a continuation of a strong surface

melt pressure for the austral summer of 2016-2017. Image

source: Climate

Reanalyzer.)

This

week, another spate of near- or above-freezing temperatures will run

along the coastal regions of both east and west Antarctica, so the

amazing atmospheric melt pressure that we are now seeing should

continue to remain in play at least for the next seven days as

austral summer continues. As for the melt pressure coming from the

warming ocean beneath the ice shelves — that is now a year-round

feature for many locations.

Links:

Hat

tip to Shawn Redmond

Hat

tip to Jeremy in Wales

Hat

tip to Colorado Bob

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.