Climate

change: how China moved from leader to laggard

Beijing’s

U-turn on renewables is triggering alarm ahead of UN meeting

FT,

24 November, 2019

The

smoggy city of Baoding is known for two things: donkey burgers, and

solar panels. An industrial centre just south of Beijing — 45

minutes via high-speed rail — the city’s high-tech zone styles

itself as “Power Valley” because it is home to so many solar

manufacturers.

But

for Vincent Yu, deputy general manager at Yingli Solar, one of the

first renewables companies to set up in the city, business has been

difficult lately. “These last two years, there has been a lot of

pressure. The subsidies for solar projects have fallen,” Mr Yu

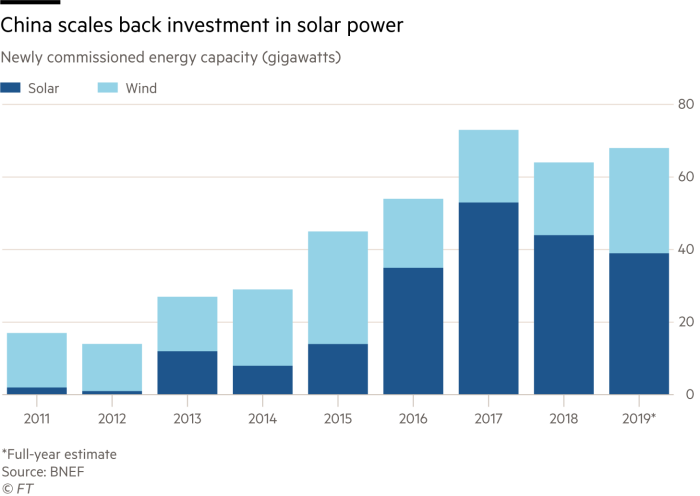

says. New solar installations in China — running at 53 gigawatts in

2017 when demand peaked — will be about 40 per cent lower this

year, he estimates.

The

photographs in his office show Yingli in its glory days a decade ago.

Sales were surging and the company spent millions sponsoring the 2010

and 2014 football World Cup tournaments. Yingli was the world’s

largest solar-panel maker in 2012 and 2013, exporting all over the

globe and celebrated in China as a national champion. Its huge

factory campus in Baoding still nods to that status, with a spacious

museum dedicated to the company’s history as a solar pioneer.

Today

Yingli is insolvent. It has been defaulting on debt payments since

2016, and in 2018 it was kicked off the New York Stock Exchange

because its market capitalisation had sunk below the minimum $50m

threshold. Although Yingli still makes solar panels, its factories

operate at a loss and the most valuable asset it has left is the land

underneath them. Some question how Yingli is still operating. But

analysts believe the political connections of its founder may have

helped stave off creditors.

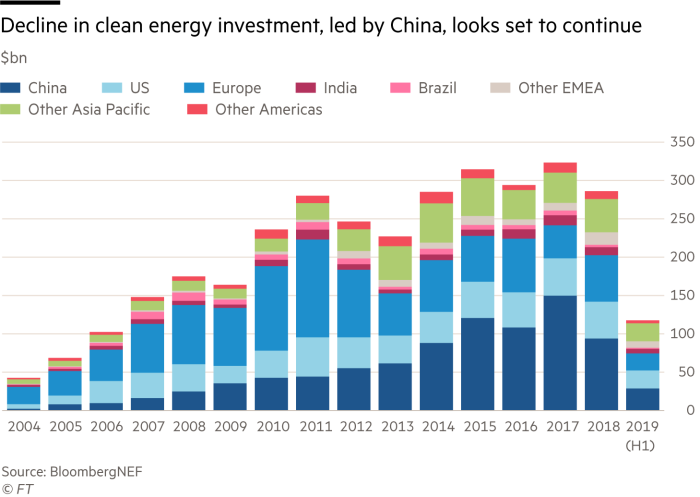

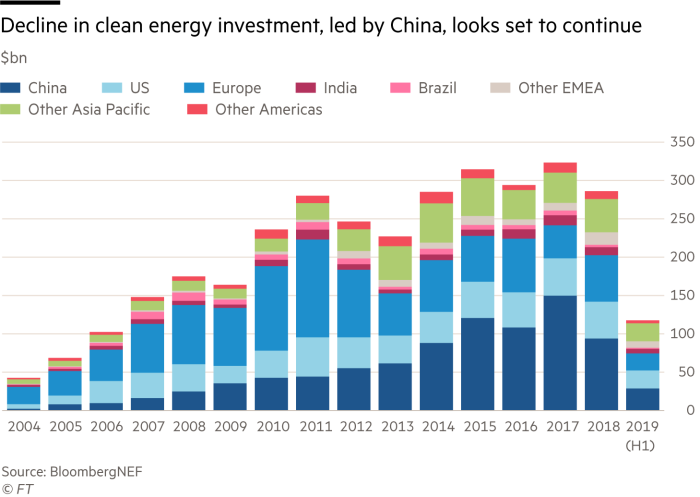

The

company is the highest profile casualty of a change in policy that is

being felt across the renewable energy sector in a country once

celebrated as the world’s clean energy champion. Chinese investment

in clean energy is plummeting — down from $76bn during the first

half of 2017, to $29bn during the first half of this year.

For

the annual UN climate talks, starting next Monday, that is alarming.

Concerns

over the impact of climate change have never been higher. But the gap

between what countries should be doing, and what they are actually

doing — pumping rising levels of carbon dioxide into the air —

has never been greater. With the US withdrawing from the Paris

climate accord, an increasing amount of attention is on China.

The

country is both the greenest in the world, but also the most

polluting. It has more wind and solar power than anybody else, yet it

is also the world’s biggest builder of new coal plants. Last year,

its emissions hit a record high, accounting for more than half of the

global increase in energy-related CO2 emissions in 2018, according to

the International Energy Agency. This year, Chinese emissions are

expected to grow about 3 per cent from 2018.

“Everything

is at stake for the planet, because the Chinese economy is so much

bigger than any other,” says Adair Turner, chair of the Energy

Transitions Commission. “Even the whole of Europe is considerably

less than Chinese emissions.”

He

points to China’s current pledge, that its CO2 emissions will peak

by 2030, and says it is nowhere near ambitious enough. “Let’s be

clear, if that was all China ever did, then we are on the path to

climate disaster,” says Lord Turner, who is lobbying for China to

consider a target of net zero emissions by 2050. “That is true of

all the [countries that have made pledges under the Paris

accord] . . . everyone has always known there would have to

be very significant improvements, to get us anywhere close to 2C.”

The

Paris climate accord, of which China is a signatory, pledges to limit

global warming to well below 2C. But that goal looks increasingly out

of reach. The world is on track for 3C of global warming by the end

of this century, if current trends continue. That would mean higher

sea levels of as much as 1m, threatening more than 600m people in

low-lying and coastal areas, according to a recent report from the

UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The

climate pact is under attack from many sides, and the US is

withdrawing from the agreement entirely, on President Donald Trump’s

orders. Fraying multilateralism has further eviscerated the climate

accord, which lacks any enforcement mechanism. China — distracted

by a slowing economy, the US trade war and protests in Hong Kong —

is not the only reason why the planet is on course for devastating

climate change, but it is near the top of the list.

“The

general momentum on climate and environment issues has been declining

[in China],” says Li Shuo, senior global policy adviser at

Greenpeace. Climate change has become a lower priority for Beijing.

“There is less space for the green agenda,” he says.

China’s

investment in renewable energy fell 39 per cent in the first half of

this year, compared with the same period in 2018, according to data

from Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Beijing yanked subsidies for solar

panel projects in the middle of last year, and is shrinking those for

wind, causing an abrupt shift.

“This

is probably a low point,” says Li Junfeng, a senior renewable

energy

policymaker

and head of the National Centre for Climate Change Strategy Research,

part of the government planning ministry. “The new policy is not in

place yet, and the old policy [of subsidies] has been stopped.”

Five

years ago, when the economy was growing robustly, Beijing saw

stronger environmental policies as core to its economic

transformation away from energy-intensive heavy industry. Today, with

the economy growing at its slowest pace since the early 1990s, that

has changed.

“The

highest political priority in China is trying to stabilise the

economy,” says Kevin Tu, an energy economist who previously led the

China desk at the IEA. “Anything else, including environmental

protection, especially climate change, will have to make some room

for these political priorities.”

On

paper, China’s climate targets have not changed: Beijing has

pledged that its carbon dioxide emissions will peak by 2030, and that

it will draw 20 per cent of its primary energy from non-fossil

sources by that same date. Yet that promise would allow China to keep

increasing its emissions for the next decade, with devastating

implications for the planet. Its investments in the Belt and Road

Initiative, under which state banks have earmarked more than $30bn to

build coal-fired power plants in other countries, is also adding to

global emissions.

China’s

participation in the Paris climate pact in 2015 was heralded as a

great victory by activists. Convincing Beijing to set climate targets

was a top priority for the Obama administration. But baked into the

negotiations was an expectation that China would achieve its

emissions target much earlier than 2030. Next year will be crucial,

as countries that signed the Paris accord are supposed to submit

enhanced targets — but the mood in Beijing makes a tougher climate

goal less likely for China.

China

is world's biggest builder of new coal power plants © Getty

Mr

Li says deteriorating relations between the US and China — along

with the unrest in Hong Kong — have helped fuel a growing

nationalist sentiment and a broader anger at the west.

One

of the targets of this nationalist ire has been Greta Thunberg, the

Swedish teenage activist who is revered as a climate hero in some

parts of the world. “Many netizens see [Greta] as representing the

general liberal western agenda,” says Mr Li. “There is this

larger perspective that the west is ganging up against China.”

At

the same time, coal appears to be again in the ascendant with Li

Keqiang, China’s premier, last month identifying it as a priority

area. China remains the world’s biggest producer. Many see this as

part of a growing focus on energy security in Beijing, a result of

Chinese leaders being spooked by deteriorating relations with the

west. “Energy security anxiety is a blessing for the coal [sector]

in China,” says Mr Tu.

Policymakers

are also focused on keeping the cost of power cheap to help stimulate

the economy, so from January the price of electricity from coal-fired

power plants, which is centrally regulated, will be allowed to

fluctuate, and is expected to fall.

These

factors have compounded the pain for the renewable energy industry.

After benefiting from generous subsidies for more than a decade,

Beijing axed solar subsidies without warning last year. The payments

due have created a deficit of around Rmb200bn ($28bn) in the

renewable energy development fund that was paying out the subsidies.

Frank

Haugwitz, founder of Asia Europe Clean Energy (Solar) Advisory in

Hong Kong, says the subsidies contributed to a solar surge that

exceeded the government’s expectations, triggering the sudden cut.

The

dice are now loaded in coal’s favour. The new policies for

renewable energy are focused on grid parity — only building wind

and solar projects that can compete with the price of coal. Yet with

coal power prices dropping, and a glut of new coal-fired power

stations coming online, it may be challenging for wind and solar to

compete. In the wind industry, there has been a rush of projects this

year as developers try to capture the last of the subsidies.

The

diplomatic pressure on China to improve its climate targets has been

played out in public. During a state visit from Emmanuel Macron, the

French president, earlier this month, both sides issued a joint

declaration, vowing that the Paris climate deal was “irreversible”,

and promising new climate targets aimed at the middle of the century.

Chinese

policymakers such as Li Junfeng say the pressure is misplaced, as

China is likely to exceed existing climate targets, even if it does

not officially adopt new goals. “Now that the US has withdrawn from

the Paris agreement, the entire global response to climate change is

shifting,” he says. “We have to be realistic . . . There’s

no point in being in a rush.”

He

also points out that China has achieved, and far surpassed, most of

its previous climate targets. A pledge to cut carbon intensity —

the amount of carbon produced per unit of GDP — by between 40 and

50 per cent by 2020, compared with 2005 levels, was achieved three

years early. It also overachieved on its targets for solar

installations, although this runaway growth led to the subsidy

deficit.

For

many years, action on climate change was the one area that Beijing

and western capitals could usually agree on. Even the most hawkish

western politician would hold up China’s climate record as an

example to be praised.

But

that may be changing. “It is going to sour for sure, if China

doesn’t move in the right direction, quickly enough,” says Todd

Stern, the chief US negotiator for the Paris agreement, who adds

there is simply “less leeway” now in terms of global emissions.

“We can’t possibly do what we need to do, unless China is doing

quite a bit.”

“We

are sort of entering a new world now . . . It is not just a

sense of urgency, it is the math. Do the math, and you will see

whether we are doing enough,” says Mr Stern. “The Paris agreement

is going to rise and fall, on the level of political will in

constituent countries. That has always been true.

“The

fault is that there is a lack of political will in virtually every

country, compared to what there needs to be.”

Solar

eclipsed: a pioneering panel-maker retrenches

The

Yingli Solar plant in Baoding © Kevin Frayer/Getty

Stepping

on to the Yingli campus in Baoding is like stepping back in time.

Employees wear a dark navy jumpsuit with the Yingli sunburst logo on

one shoulder and a Chinese flag on the other, giving the place a

distinctly communal feel. In front of a large assembly yard, a big

stage is decorated in honour of the recent 70th anniversary of the

founding of the People’s Republic of China, plastered with slogans

such as “remember your mission” and “help each other”.

The

company’s problems began at least five years ago, as mounting debt

levels combined with plummeting panel prices. Its dire financial

situation became evident in May 2016, when Yingli failed to meet a

$270m loan payment. Discussions with debtholders, the largest of

which is China Development Bank, have since failed to reach

conclusion. Shareholders fear the worst: Yingli’s shares on the

pink sheets — the over-the-counter market for companies not listed

on a major exchange — are trading at just 15 cents a share. The cut

in government subsidies for solar projects has only compounded the

challenges.

Miao

Liansheng, the founder who started his career in the army before

becoming an entrepreneur, was once ranked among China’s richest

individuals. Mr Miao lives on the Yingli campus, and employees say

that he still makes daily appearances to chat with workers.

But

today there are fewer workers than there used to be. Many of the

factory production lines are quiet. It’s not clear if some are

under maintenance, or if they have simply been idled. The company

once had around 20,000 employees, but that has fallen to just over

6,000, according to deputy general manager Vincent Yu. This year it

will produce panels with capacity of 2.5GW-3.5GW, he says, equivalent

to about 3 per cent of global demand.

The

Yingli museum shows that the company was, in many ways, a pioneer. It

boasted the first automatic soldering equipment in China in 2005 and

the first automatic module production line in 2007. But its equipment

quickly became outdated, allowing newer entrants to undercut them.

Starting

a decade ago, China’s state support for solar panel manufacturers

led to overcapacity and vicious price wars. This pushed down the

price of solar panels — to the benefit of the rest of the world —

but meant that margins were razor-thin, or negative, for panel

manufacturers in China.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.