Melting permafrost in Siberia is creating climate change refugees

Villagers who once thrived along the Zyryanka river are seeing the formerly stable ground warping beneath their feet, exposing previously entombed plants and animals.

By Anton Troianovski and Chris Mooney

On

the Zyryanka river in Russia, Andrey

Danilov eases his motorboat on to the gravel riverbank, where the

bones of a woolly mammoth lie scattered on the beach. A putrid odour

fills the air – the stench of ancient plants and animals

decomposing after millennia entombed in a frozen purgatory.

“It

smells like dead bodies,” Danilov says. The skeletal remains were

left behind by mammoth hunters, hoping to strike it rich by pulling

prehistoric ivory tusks from a vast underground layer of ice and

frozen dirt called permafrost.

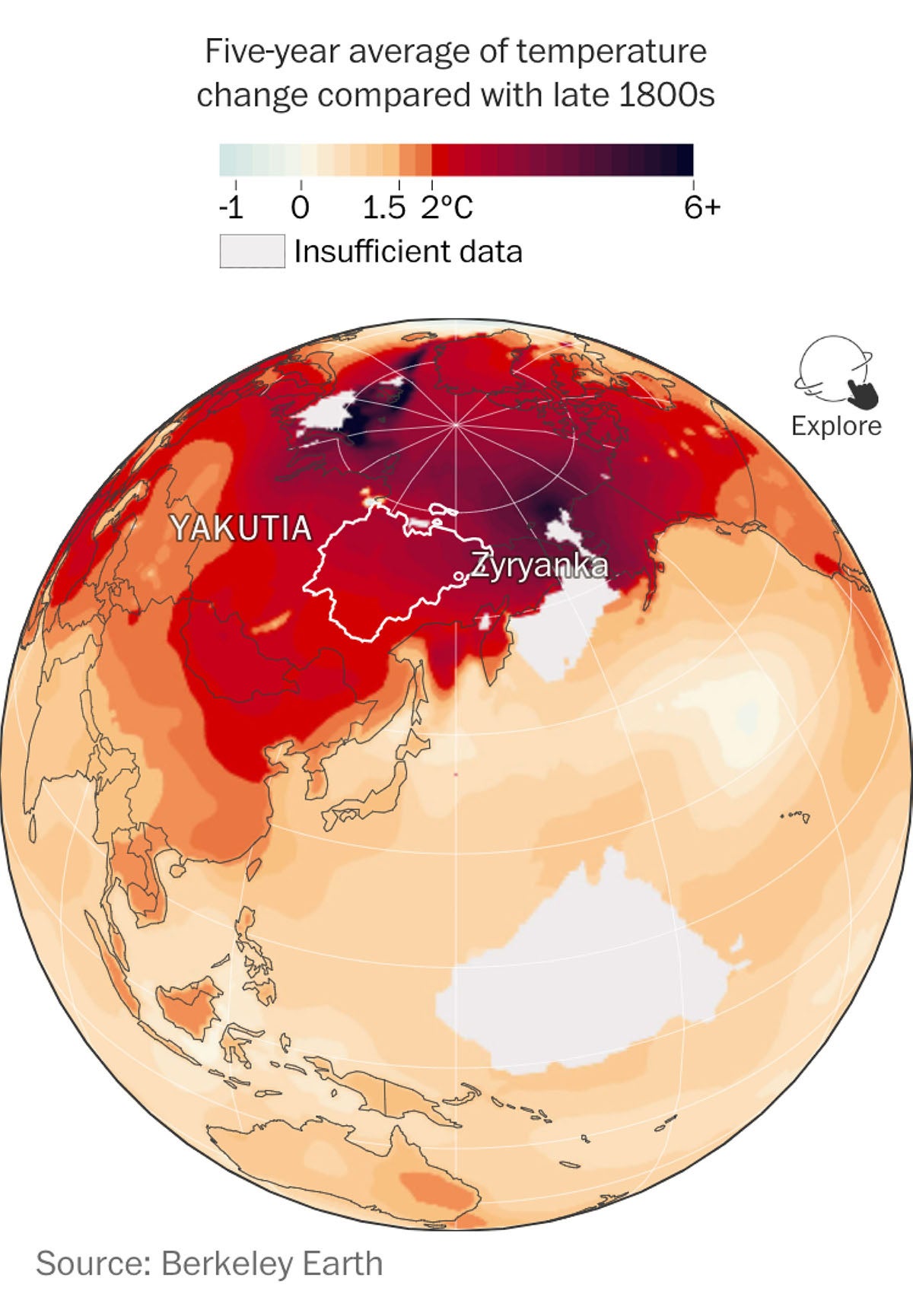

It has been rapidly thawing because Siberia is

warming up faster than almost anywhere else on Earth. Scientists

say the planet’s warming must not exceed 1.5C, but Siberia’s

temperatures are already far beyond that.

Washington

Post analysis

has found that the area near the town of Zyryanka, in an enormous

wedge of eastern Siberia called Yakutia, has warmed by more than 3C

since preindustrial times – roughly three times the global

average.

The

permafrost that once sustained farming – and upon which villages

and cities are built – is in the midst of a great thaw, blanketing

the region with swamps, lakes and odd bubbles of earth that render

the land virtually useless. “The warming got in the way of our

good life,” says Alexander Fedorov, deputy director of the Melnikov

Permafrost Institute in the regional capital of Yakutsk. “Every

year, things are getting worse and worse.”

For

the 5.4 million people who live in Russia’s permafrost zone, the

new climate has disrupted their homes and their livelihoods. Rivers

are rising and running faster and entire neighbourhoods are

falling into them. Arable land for farming has plummeted by more than

half, to just 120,000 acres in 2017.

In

Yakutia, an area one-third the size of the US, cattle and reindeer

herding has plunged 20 per cent, because the animal battle to

survive the warming climate’s destruction of pasture

land. Siberians who grew up learning to read nature’s subtlest

signals are being driven to migrate by a climate they no longer

understand.

This

migration from the countryside to cities and towns – also driven by

factors such as low investment and scarce internet connection –

represents one of the most significant and little-noticed movements

of climate refugees. The city of Yakutsk has seen its population

surge 20 per cent to more than 300,000 in the past decade.

And

then there’s the smell: as the permafrost thaws, animals and plants

frozen for thousands of years begin to decompose and send a steady

flow of carbon dioxide and other gases into the atmosphere,

accelerating climate

change.

“The permafrost is thawing so fast,” says Anna Liljedahl, an

associate professor at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, “we

scientists can’t keep up anymore.”

Against

this backdrop, a booming cottage industry in mammoth hunting has

taken hold. The creatures’ long-frozen tusks, combined with

Chinese demand for ivory, have imbued struggling local economies

with a strike-it-rich ethos. Some people bask in the sudden influx of

money, but others watch in dismay as Siberia’s way of life is

washed away.

The

first sign of change was the birds. Over the past few decades, new

species started to show up in the Upper Kolyma District, an area on

the Arctic

Circle in

northeastern Siberia 1,000 miles west of Nome, Alaska. These new

arrivals included the mallard duck and barn swallow, whose normal

range was previously much further to the south. A study published by

Yakutsk scientist Roman Desyatkin last year stated that

ornithologists in the region have identified 48 new bird species in

the past half century – an increase of almost 20 per cent in

the known diversity of bird life.

Then the land started to change. Winters, though still brutal, turned milder and shorter. Fed by the rapidly thawing permafrost, rivers began flooding more, leaving some communities inaccessible for months and washing others away, along with the ground beneath them.

The

village of Nelemnoye was cut off for three months in late 2017, when

the lakes and rivers didn’t fully freeze, stranding residents who

use the frozen waters for transport. With the village in crisis, the

government dispatched a helicopter to take residents grocery

shopping.

Claudia

Shalugina, 63, used to teach at the three-storey school in Zyryanka,

a 90-minute motorboat ride downriver. Around 10 years ago, the Kolyma

river washed away a section of Zyryanka, taking Shalugina’s school

with it. Satellite images show the loss of approximately 50 acres of

land along the riverside, according to the geographic information

firm Esri. Smoking a cigarette on the porch of the village library,

Shalugina offers her own analysis of the changing climate: “I

think, ‘Lord, it’s probably going to be the end of the world.’

”

Just

downstream from where the Zyryanka river flows into the mighty

Kolyma, three huge tractor trailers stand abandoned on the forested

riverbank. Weeds and wildflowers rise up around them. The frozen

river, used as a winter ice road, suddenly became too risky to drive

on. Spring had come early this year – again. “It used to be man

was in control,” says Pyotr Kaurgin, head of the Chukchi indigenous

community in the village of Kolymskoye, on the northern reaches of

the Kolyma river. “Now nature is in control.”

In

the summer, enormous fires tore through Siberian boreal forests,

unleashing yet more carbon into the atmosphere. Some scientists fear

worsening northern fires are amplifying the permafrost damage.

Meanwhile, six time zones away (but still in Siberia) on the Yamal

Peninsula, monstrous craters have opened up in the tundra. Scientists

suspect they represent sudden explosions of methane gas freed by

thawing permafrost.

Outside

Zyryanka, a once bustling farm has given way to a jumbled landscape

of dips, bumps, and puddles. The mud road, what’s left of it, banks

and turns at head-spinning angles until it runs into a widening

pond. “The earth is slowly sinking,” horse farmer Vladimir

Arkhipov says. “There’s more and more water and less and less

usable earth.”

The

impact on farming has been catastrophic. Arkhipov produces fermented

mare’s milk called kumys, a delicacy among the Sakha, the Turkic

people who make up roughly half the population of Yakutia. Arkhipov

also raises foals for meat, which, in Sakha culture, is sometimes

consumed, sliced thin, raw and frozen.

In

the past five years, Arkhipov says, he has lost close to four of his

70-odd acres of hay fields to permafrost-related flooding, meaning he

can feed three fewer horses in the winter. And during a freak

blizzard in late 2017 – an increasingly common occurrence in the

region as the climate changes, scientists say – 10 of his horses

died.

Due

to thawing permafrost – along with the demise of Soviet-era state

farms – the area of cultivated land in Yakutia has plummeted by

more than half since 1990. The region’s cattle herds have shrunk by

about 20 per cent, to 188,100 head in 2017 from 233,300 in 2011.

Reindeer herds have also declined sharply.

Fedorov

and other scientists say the degradation of crop and pastureland

caused by the thawing permafrost helped bring about the collapse of

the region’s agriculture.

Yegor

Prokopyev, the retired head of Nelemnoye, says climate change is the

latest shock to befall the Kolyma river region. There was communism

and forced collective farming, then capitalism and government

cutbacks. His grandfather, a peasant, was declared an enemy of the

working class and sent to one of this region’s many gulag prison

camps.

“As

soon as you start getting used to something, they’ll come up with

something else, and you have to adapt to everything all over again,”

Prokopyev says.

The

idea that warming brings disaster is ingrained in the tradition of

the Sakha people of Yakutia, the region laced by the Zyryanka and

Kolyma rivers. An old Sakha prophecy says: “They will survive until

the day when the Arctic Ocean melts.”

Village

elders recalled the phrase after an episode of catastrophic flooding

in 2005, according to Susan Crate, an anthropologist at George Mason

University, who has long studied climate change in Siberia. The

radical transformation underway here, she says, should serve as a

warning to people in every corner of the globe. “Changing our ways

is imminent,” Crate says.

Over

the past 50 years, temperatures across most of Yakutia have risen at

double or even triple the global average rate, according to work by

Yakutsk-based scientists Fedorov and Alexey Gorokhov. The town of

Zyryanka has warmed by just over 2C from 1966 to 2016, according to

their analysis.

The Post’s analysis, which uses a data set from Berkeley Earth, looks further back. It shows that Zyryanka and the roughly 2,000-square-mile area surrounding it has warmed by more than 3C when the past five years are compared with the mid- to late 1800s. Some regions of Siberia bordering on the Arctic Ocean are warming even faster, the analysis shows.

Desyatkin,

at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Yakutsk, found that the changes

are even more dramatic underground. From 2005 to 2014, his team

found, the number of days with below-freezing temperatures three feet

below the surface fell from around 230 days a year to 190. That is

significant because enormous wedges of ice lie under Yakutia.

In some parts of the world, permafrost lies in a relatively thin layer just below the ground’s surface. But in much of Yakutia, the permafrost is of a special, icy and far thicker variety. Scientists call it Yedoma. Formed during the late Pleistocene, the Earth’s last glacial period, which ended about 11,700 years ago, Yedoma consists of thick layers of soil packed around gigantic lodes of embedded ice. Because Yedoma contains so much ice, it can melt quickly – reshaping the landscape as sudden lakes form and hillsides collapse.

Around

Zyryanka, exposed ice wedges glisten along the riverbanks. Their

slick, muddy surfaces form ghostly, moonlike grooves. Plant roots

dangle like Christmas ornaments from the top layer of soil, left

behind as the ice below it melts.

In

the 1970s, Desyatkin says, the ground in the Middle Kolyma District,

just north of Zyryanka, thawed to a depth of about two feet every

summer. Now it thaws to more than three feet. That extra foot of

thawing means that, on average, every square mile of territory has

been releasing an additional 700,000 gallons of water into the

environment every year, according to Desyatkin’s calculations.

Meanwhile,

ancient plant and animal remains trapped inside the Yedoma are

exposed to non-freezing temperatures – or even the open air. That,

in turn, activates microbes, which break down the remains and unleash

carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, especially from the thawing plant

material.

Scientists

estimate that the Earth’s Yedoma regions contain between 327

billion and 466 billion tons of carbon. Were it all released into the

atmosphere, that would amount to more than half of all human-caused

emissions from greenhouse gases and deforestation between 1750 and

2011.

Although

the thawing of these ancient remains raises the threat of terrifying

consequences, it is, for some, the bright side of climate change.

“The thawing of the permafrost has a very good effect. The mammoth

bone comes out and brings us money,” says Yevgeny Konstantinov, a

newspaper editor in the Arctic town of Saskylakh. “Everyone rides

Jeeps now.”

In

recent years, demand from China has created a booming market for

mammoth ivory. People in Yakutia collected almost 80 tons in 2017,

according to official figures – a likely undercount, experts say. A

Yakutia official recently estimated annual sales to be as high as

$63m (£50m).

As

the permafrost thaws and riverbanks erode, more tusks will emerge.

Though mammoths disappeared from the Siberian mainland some 10,000

years ago, the government estimates that 500,000 tons of their tusks

are still buried in the frozen ground.

Supply

and demand are so great that some people are collecting mammoth tusks

at near-industrial scale. They use high-pressure hoses to blast away

riverbanks and hire teams of young men to comb the wilderness for

months at a time. People involved in the business, which isn’t

entirely legal, say some tusk prospectors have deployed underwater

cameras and scuba gear.

A

decaying bust of Vladimir Lenin sits on the banks of the Kolyma river

“You

get bit once, you catch the bug. It’s like a gold rush,” says

Alexey Sivtsev, a prospector in Zyryanka who says he is licensed to

collect tusks. In the glutted market, Sivtsev says, the price for top

quality tusks has fallen from about $500 per pound five years ago to

around $180.

According

to Sakha tradition, tusk-hunting violates the sacred ground and

brings bad tidings. Some Siberians worry that it also draws young

people into an underworld linked to organised crime. “Since all

this is connected to criminality, I’m worried that this mafia, as

we call it, is getting a basis for existing in our villages,” says

Vyacheslav Shadrin, who studies northern indigenous peoples at the

Russian Academy of Sciences in Yakutsk.

Konstantin

Gusev, a hunter in Nelemnoye, is still waiting for his mammoth

payday. Once, he found the tusk of an ancient woolly rhinoceros, but

threw it away. He later learned that such a find sells for $7,000 per

pound, making it among the most valuable animal remains buried

underground. Gusev now has his eye on a strip of riverbank where he

found a mammoth tooth. He invested in a water pump and hose to try to

uncover what’s underneath.

Vanda

Ignatyeva, a Yakutsk sociologist, says climate change is leaving

people with few choices: “They have to somehow support and feed

their families.”

The

mammoths aren’t enough to keep Gusev in the countryside, however:

the hunter says he is moving to Yakutsk to look for other kinds of

work.

Andrei

Zimzyulin lounges at his fishing camp on the riverbank

The

ducks and geese are just about gone, he says, moving possibly to new

habitats in Siberia as the climate shifts. The sable pelts aren’t

as thick as they used to be; the shorter winters mean that once

reliably frozen-over lakes and rivers are now less predictable,

making hunting grounds more difficult to reach and restricting his

ability to get goods to market. “Something is changing,” Gusev

says. “People are sitting around, trying to survive.”

In

Nelemnoye, the population has declined to 180 from 210 in the past

decade, according to village head Andrei Solntsev. Just 82 of the

residents have work. Many factors are pushing people to move to the

city – lack of internet access, poor flight connections, limited

job opportunities – but the uncertainty born of a changing climate

looms over everything.

Innokenty

Dyachkov pulls a pike out of a tub in Nelemnoye. Fishing is the

lifeblood of the village

“We’re

already seeing the phenomenon of climate refugees,” Shadrin says.

But “it’s not like anyone is waiting for them here” in the

city, he states. “No one is ready to help them immediately...

They’re breaking away, becoming marginals.”

And

Yakutsk offers no escape from the warming climate. As the permafrost

thaws and recedes, a handful of apartment buildings there are showing

signs of structural problems. Sections of many older, wooden

buildings already sag towards the ground, rendered uninhabitable by

the unevenly thawing earth. New apartment blocks are being built on

massive pylons, extending ever deeper – more than 40 feet – below

ground.

The

Kolyma river, seen through the windows of a hunting lodge

“The

cold is our protection,” Yakutsk Mayor Sardana Avksentyeva says.

“This isn’t a man-made catastrophe yet, but it’ll be

unavoidable if things continue at this pace.”

An

international team of scientists, led by Dmitry Streletskiy at George

Washington University, estimated in a study published this year that

the value of buildings and infrastructure on Russian permafrost

amounts to $300 billion – about 7.5 per cent of the nation’s

total annual economic output. They estimate the cost of mitigating

the damage wrought by thawing permafrost will probably total more

than $100bn by 2050.

But

people here are used to adapting. They survived the forced

collectivisation of the early Soviet Union. Gulag prisoners taught

them to grow potatoes. After the Soviet Union collapsed and the state

farms closed, they shifted to a greater reliance on hunting and

fishing.

Now,

Anatoly Sleptsov, 61, is once again embracing change. The pastures of

the village where he used to live have turned into swamps and lakes.

So he moved to firmer ground outside Zyryanka, where he’s

leveraging climate change to his advantage.

Though

Sleptsov’s attempt to create an Israeli-style kibbutz failed, he

figures the region can profit by marketing omega 3 fatty acids

extracted from its fish. Meanwhile, his potatoes are flowering

earlier and this year he started growing strawberries. “Next

thing,” he says, “we’ll have watermelon.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.