The

Depression Of The 1930s Was An Energy Crisis

19

December, 2017

Economists, including

Ben Bernanke,

give all kinds of reasons for the Great Depression of the 1930s. But

what if the real reason for the Great Depression was an energy

crisis?

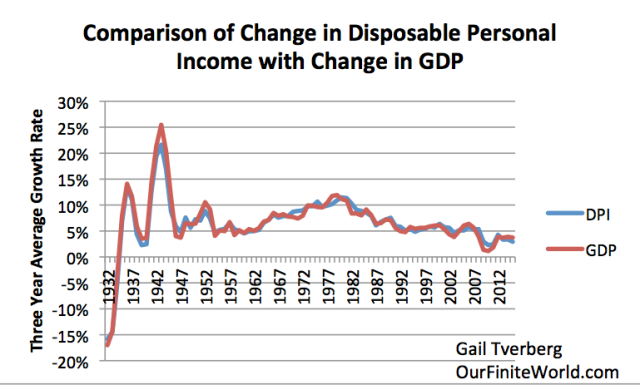

When

I put together a chart of per capita energy consumption since

1820 for

a post back in 2012,

there was a strange “flat spot” in the period between 1920 and

1940. When we look at the underlying data, we see that coal

production was starting to decline in some of the major coal

producing parts of the world at that time. From the point of view of

people living at the time, the situation might have looked very much

like peak energy consumption, at least on a per capita basis.

Figure

1. World Energy Consumption by Source, based on Vaclav Smil

estimates from Energy Transitions: History, Requirements and

Prospects (Appendix) together with BP Statistical Data for 1965 and

subsequent, divided by population estimates by Angus Maddison.

Even

back in the 1820 to 1900 period, world per capita energy had

gradually risen as an increasing amount of coal was used. We

know that going back a very long time, the use of water and wind had

never amounted to very much (Figure 2) compared to burned biomass and

coal, in terms of energy produced. Humans and draft animals were also

relatively low in energy production. Because of its great

heat-producing ability, coal quickly became the dominant fuel.

Figure

2. Annual energy consumption per head (megajoules) in England and

Wales during the period 1561-70 to 1850-9 and in Italy from 1861-70.

Figure by Wrigley

In

general, we know that energy products, including coal, are

necessary to enable processes that contribute to economic growth.Heat

is needed for almost all industrial processes. Transportation needs

energy products of one kind or another. Building roads and homes

requires energy products. It is not surprising that the Industrial

Revolution began in Britain, with its use of coal.

We

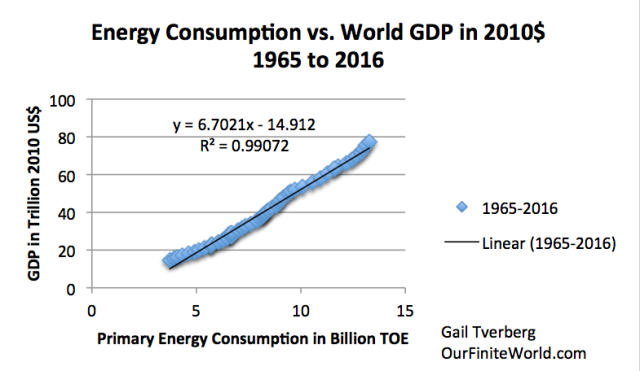

also know that there is a long-term correlation between world GDP

growth and energy consumption.

Figure

3. X-Y graph of world energy consumption (from BP Statistical Review

of World Energy, 2017) versus world GDP in 2010 US$, from World

Bank.

The

“flat period” in 1920-1940 in Figure 1 was likely problematic.

The economy is a self-organized networked system; what was wrong

could be expected to appear in many parts of the economy. Economic

growth was likely far too low. The chance for conflict among nations

was much higher because of stresses in the system–there was not

really enough coal to go around. These stresses could extend to the

period immediately before 1920 and after 1940, as well.

A Peak in Coal Production Hit UK, United States, and Germany at Close to the Same Time

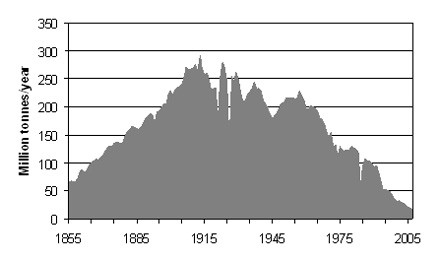

This

is a coal supply chart for UK. Its peak coal production (which was an

all time peak) was in 1913. The UK was the largest coal producer in

Europe at the time.

Figure

3. United Kingdom coal production since 1855, in figure

by David Strahan.

First published in New Scientist, 17 January 2008.

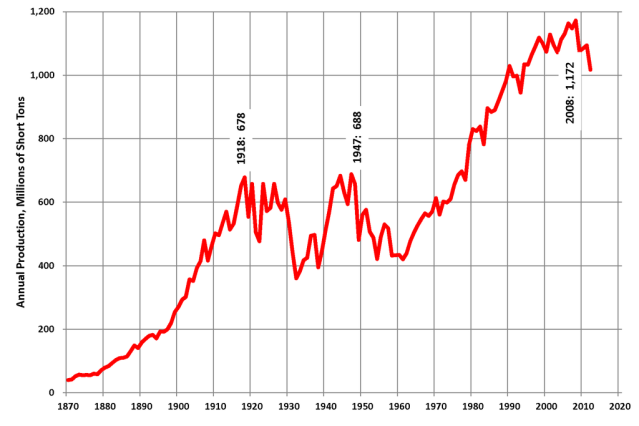

The

United States hit a peak in its production only five years later, in

1918. This peak was only a “local” peak. There were also later

peaks, in 1947 and 2008, after coal production was developed in new

areas of the country.

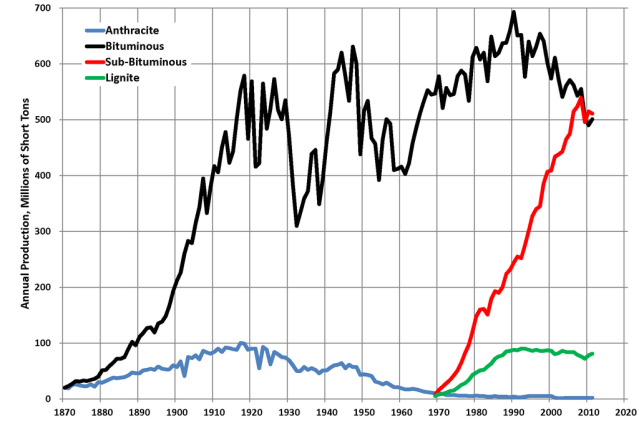

By

type, US coal production is as shown on Figure 5.

Evidently,

the highest quality coal, Anthracite, reached a peak and began to

decline about 1918. Bituminous coal hit a peak about the same time,

and dropped way back in production during the 1930s. The poorer

quality coals were added later, as the better-quality coals became

less abundant.

The

pattern for Germany’s hard coal shows a pattern somewhat in between

the UK and the US pattern.

Germany

too had a peak during World War I, then dropped back for several

years. It then had three later peaks, the highest one during World

War II.

What Affects Coal Production?

If

there is a shortage of coal, fixing it is not as simple as

“inadequate coal supply leads to higher price,” quickly followed

by “higher price leads to more production.” Clearly

the amount

of coal resource in the ground affects

the amount of coal extraction, but other things do as well.

[1] The

amount of built infrastructure for

taking the coal out and delivering the coal. Usually, a

country only adds a little coal extraction capacity at a time and

leaves the rest in the ground. (This is how the US and Germany could

have temporary coal peaks, which were later surpassed by higher

peaks.) To add more extraction capacity, it is necessary to add

(a) investment needed for getting the coal out of the ground as

well as (b) infrastructure for delivering coal to potential users.

This includes things like trains and tracks, and export terminals for

coal transported by boats.

[2] Prices

available in the marketplace for coal.

These fluctuate widely. We will discuss this more in a later section.

Clearly, the higher the price, the greater the quantity of coal that

can be extracted and delivered to users.

[3] The

cost of extraction, both in existing locations and in new locations.

These costs can perhaps be reduced if it is possible to add new

technology. At the same time, there is a tendency for costs within a

given mine to increase over time, as it becomes necessary to access

deeper, thinner seams. Also, mines tend to be built in the most

convenient locations first, with best access to transportation. New

mines very often will be higher cost, when these factors are

considered.

[4] The

cost and availability of capital (shares

of stock and sale of debt) needed for building new infrastructure,

and for building new devices made possible by new technology. These

are affected by interest rates and tax levels.

[5] Time

lags needed to implement changes.

New infrastructure and new technology are likely to take several

years to implement.

[6] The

extent to which wages can be recycled into demand for energy

products.

An economy needs to have buyers for

the products it makes. If a large share of the workers in an economy

is very low-paid, this creates a problem.

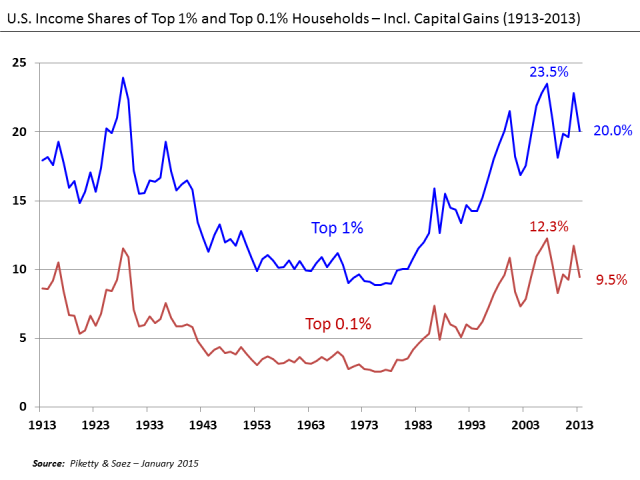

If

there is an energy shortage, many people think of the shortage as

causing high prices. In fact, the shortage is at least equally likely

to cause greater wage disparity. This might also be considered a

shortage of jobs that pay well.

Without

jobs that pay well, would-be workers find it hard to purchase the

many goods and services created by the economy (such as homes, cars,

food, clothing, and advanced education). For example, young adults

may live with their parents longer, and elderly people may move in

with their children.

The

lack of jobs that pay well tends to hold down “demand” for goods

made with commodities, and thus tends to bring down commodity prices.

This problem happened in the 1930s and is happening again today. The

problem is an affordability problem,

but it is sometimes referred to as “low demand.” Workers

with inadequate wages cannot afford to

buy the goods made by the economy. There

may be a glut of a commodity (food, or oil, or coal), and commodity

prices that fall far below what producers need to make a profit.

The Fluctuating Nature of Commodity Prices

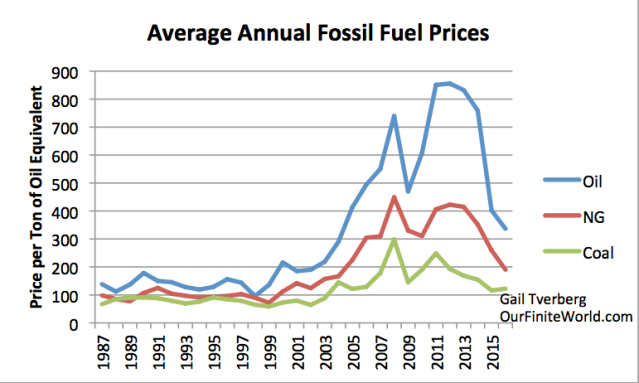

I

have noted in the past that fossil fuel prices tend to move together.

This is what we would expect, if affordability is a major issue, and

affordability changes over time.

Figure

8. Price per ton of oil equivalent, based on comparative prices for

oil, natural gas, and coal given in BP Statistical Review of World

Energy. Not inflation adjusted.

We

would expect metal prices to follow fossil fuel prices, because

fossil fuels are used in the extraction of ores of all

kinds. Investment strategist Jeremy Grantham (and his company

GMO) noted this correlation among commodity prices, and put together

an index of commodity prices back to 1900.

Figure

9. GMO Commodity Index 1900 to 2011, from GMO

April 2011 Quarterly Letter.

“The Great Paradigm Shift,” shown at the end is not really the

correct explanation, something now

admitted by Grantham.

If the graph were extended beyond 2010, it would show high prices in

2010 to 2013. Prices would fall to a much lower level in 2014 to

2017.

Reason

for the Spikes in Prices. As

we will see in the next few paragraphs, the spikes in prices

generally arise in situations in which everyday goods (food, homes,

clothing, transportation) suddenly became more affordable to

“non-elite” workers. These are workers who are not highly

educated, and are not in supervisory positions. These spikes in

prices don’t generally “come about” by themselves; instead,

they are engineered by governments, trying to stimulate the economy.

In

both the World

War I and World War II price spikes,

governments greatly raised their debt levels to fund the war efforts.

Some of this debt likely went directly into demand for commodities,

such as to make more bombs, and to operate tanks, and thus tended to

raise commodity prices. In addition, quite a bit of the debt

indirectly led to more employment during the period of the war. For

example, women who were not in the workforce were hired to take jobs

that had been previously handled by men who were now part of the war

effort. (These women were new non-elite workers.) Their earnings

helped raise demand for goods and services of all kinds, and thus

commodity prices.

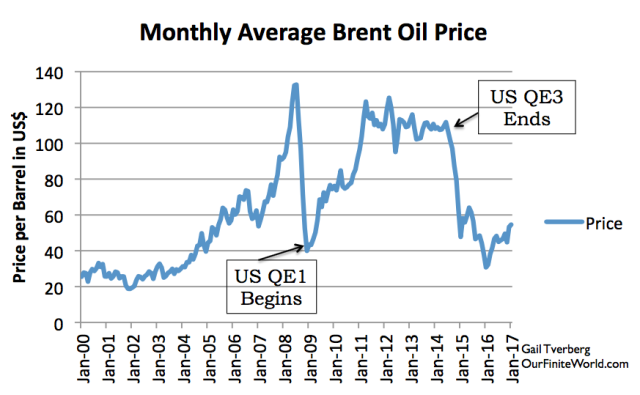

The 2008

price spike was

caused (at least in part) by a US housing-related debt bubble.

Interest rates were lowered in the early 2000s to stimulate the

economy. Also, banks were encouraged to lend to people who did not

seem to meet usual underwriting standards. The additional demand for

houses raised prices. Homeowners, wishing to cash in on the new

higher prices for their homes, could refinance their loans and

withdraw the cash related to the new higher prices. They could use

the funds withdrawn to buy goods such as a new car or a remodeled

basement. These withdrawn funds indirectly supplemented the earnings

of non-elite workers (as did the lower interest rate on new

borrowing).

The 2011-2014

spike was

caused by the extremely low interest rates made possible by

Quantitative Easing. These low interest rates made the buying of

homes and cars more affordable to all buyers, including non-elite

workers. When the US discontinued its QE program in 2014, the US

dollar rose relative to many other currencies, making oil and other

fuels relatively more expensive to workers outside the US. These

higher costs reduced the demand for fuels, and dropped fuel prices

back down again.

The

run-up in oil prices (and other commodity prices) in the 1970s is

widely attributed to US oil production peaking, but I think that the

rapid run-up in prices was enabled by the rapid wage run-up of the

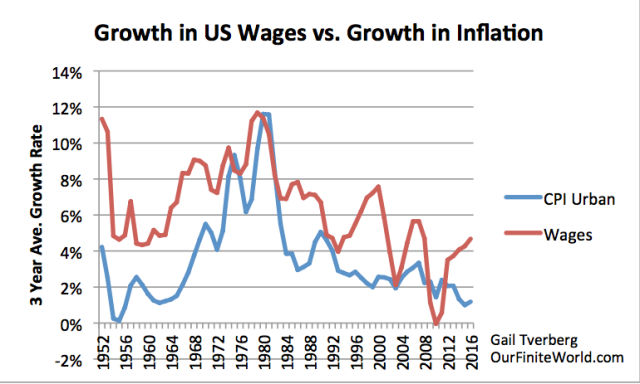

period (Figure 11 below).

Figure

11. Growth in US wages versus increase in CPI Urban. Wages are total

“Wages and Salaries” from US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

CPI-Urban is from US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The

Opposing Force: Energy prices need to fall, if the economy is to

grow. All

of these upward swings in prices can be at most temporary changes to

the long-term downward trend in prices. Let’s think about why.

An

economy needs to grow. To do so, it needs an increasing supply of

commodities, particularly energy commodities. This can only happen if

energy prices are trending lower. These lower prices enable the

purchase of greater supply. We can see this in the results of

some academic papers. For example, Roger Fouquet shows that it is not

the cost of energy, per se, that drops over time. Rather, it is the

cost of energy services that declines.

Figure

12. Total Cost of Energy and Energy Services, by Roger Fouquet,

from Divergences

in Long Run Trends in the Prices of Energy and Energy Services.

Energy

services include changes in efficiency, besides energy costs

themselves.

Thus, Fouquet is looking at the cost of heating a home,

or the cost of electrical services, or the cost of transportation

services, in inflation-adjusted units.

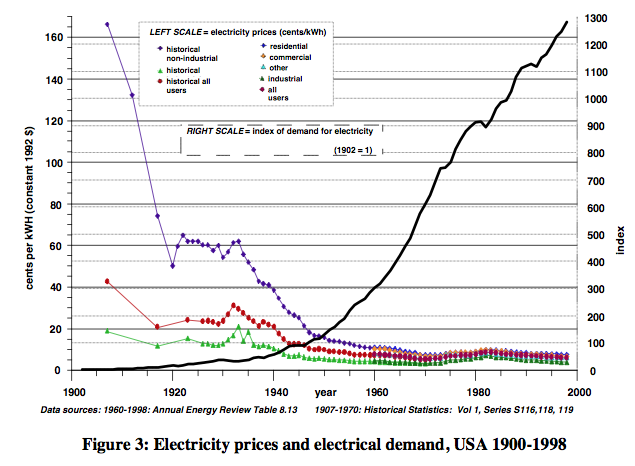

Robert

Ayres and Benjamin Warr show a similar result, related to

electricity. They also show that usage tends to rise, as prices fall.

Figure

13. Ayres and Warr Electricity Prices and Electricity Demand, from

“Accounting

for growth: the role of physical work.”

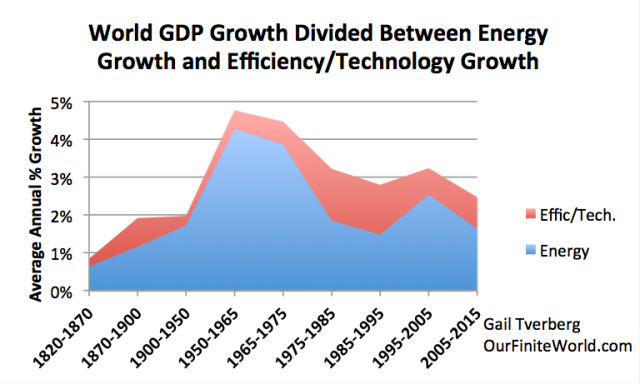

Ultimately,

we know that the growth in energy consumption tends to rise at close

to the same rate as the growth in GDP. To keep energy consumption

rising, it is helpful if the cost of energy services is falling.

Figure

14. World GDP growth compared to world energy consumption growth for

selected time periods since 1820. World real GDP trends for 1975 to

present are based on USDA

real GDP data in

2010$ for 1975 and subsequent. (Estimated by author for 2015.) GDP

estimates for prior to 1975 are based on Maddison

project updates as

of 2013. Growth in the use of energy products is based on a

combination of data from Appendix A data from Vaclav Smil’s Energy

Transitions: History, Requirements and Prospects together

with BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2015 for 1965 and

subsequent.

How the Economic Growth Pump Works

There

seems to be a widespread belief, “We pay each other’s wages.”

If this is all that there is to economic growth, all that is needed

to make the economy grow faster is for each of us to sell more

services to each other (cut each other’s hair more often, or give

each other back rubs, and charge for them ). I think this story is

very incomplete.

The

real story is that energy

products can be used to leverage human labor. For

example, it is inefficient for a human to walk to deliver goods to

customers. If a human can drive a truck instead, it leverages his

ability to deliver goods. The more leveraging that is available for

human labor, the more goods and services that can be produced in

total, and the higher inflation-adjusted wages can be. This increased

leveraging of human labor allows inflation-adjusted wages to rise.

Some might call this result, “a higher return on human labor.”

These

higher wages need to go back to the non-elite workers, in order to

keep the growth-pump operating. With higher-wages, these

workers can afford to buy goods and services made with commodities,

such as homes, cars, and food.

They can also heat their homes and

operate their vehicles. These wages help maintain the demand needed

to keep commodity prices high enough to encourage more commodity

production.

Raising

wages for elite workers (such as managers and those with advanced

education), or paying more in dividends to shareholders, doesn’t

have the same effect. These individuals likely already have enough

money to buy the necessities of life. They may use the extra income

to buy shares of stock or bonds to save for retirement, or they may

buy services (such as investment advice) that require little use of

energy.

The

belief, “We pay each other’s wages,” becomes increasingly

false, if wages and wealth are concentrated in the hands of

relatively few. For example, poor people become unable to afford

doctors’ visits, even with insurance, if wage disparity becomes too

great. It is only when wages are fairly equal that all can afford a

wide range of services provided by others in the economy.

What Went Wrong in 1920 to 1940?

Very

clearly, the first thing that went wrong was the peaking of UK coal

production in 1913. Even before 1913, there were pressures coming

from the higher cost of coal production, as mines became more

depleted. In 1912, there was a 37-day

national coal strike protesting

the low wages of workers. Evidently, as extraction was becoming more

difficult, coal prices were not able to rise sufficiently to cover

all costs, and miners’ wages were suffering. The debt for World War

I seems to have helped raise commodity prices to allow wages to be

somewhat higher, even if coal production did not return to its

previous level.

Suicide

rates seem to behave inversely compared to earning power of non-elite

workers. A study

of suicide rates in England and Walesshows

that these were increasing prior to World War I. This is what we

would expect, if coal was becoming increasingly difficult to extract,

and because of this, the returns for everyone, from owners to

workers, was low.

Figure

15. Suicide rates in England and Wales 1861-2007 by Kyla Thomas and

David Gunnell from International

Journal of Epidemiology, 2010.

World

War I, with its increased debt (which was in part used for more

wages), helped the situation temporarily. But after World War I, the

Great Depression set in, and with it, much higher suicide rates.

The

Great Depression is the kind of result we would expect if UK no

longer had enough coal to make the goods and services it had made

previously. The lower production of goods and services would likely

be paired with fewer jobs that paid well. In such a situation, it is

not surprising that suicide rates rose. Suicide rates decreased

greatly with World War II, and with all of the associated borrowing.

Looking

more at what happened in the 1920 to 1940 period, Ugo

Bardi tells us that

prior to World War I, UK exported coal to Italy. With falling coal

production, UK could no longer maintain those exports after World War

I. This worsened relations with Italy, because Italy needed coal

imported from UK to rebuild after the war. Ultimately, Italy aligned

with Germany because Germany still had coal available to export. This

set up the alliance for World War II.

Looking

at the US, we see that World War I caused favorable conditions for

exports, because with all of the fighting, Europe needed to import

more goods (including food) from the United States. After the war

ended in 1918, European demand was suddenly lower, and US commodity

prices fell. American farmers found their incomes squeezed. As a

result, they cut back on buying goods of many kinds, hurting the US

economy.

One

analysis of the economy of the 1920s tells

us that from 1920 to 1921, farm prices fell at a catastrophic rate.

“The price of wheat, the staple crop of the Great Plains, fell by

almost half. The price of cotton, still the lifeblood of the South,

fell by three-quarters. Farmers, many of whom had taken out loans to

increase acreage and buy efficient new agricultural machines like

tractors, suddenly couldn’t make their payments.”

In

1943, M. King Hubbert offered the view that all-time

employment had peaked in 1920,

except to the extent that it was jacked up by unusual means, such as

war. In fact, some

historical data shows that

for four major industries combined (foundries, meat packing, paper,

and printing), the employment index rose from 100 in 1914, to 157 in

1920. By September 1921, the employment index had fallen back to 89.

The peak coal problem of UK had been exported to the US as low

commodity prices and low employment.

It

was not until the huge amount of debt related to World War II that

the world economy could be stimulated enough so that total energy

production per capita could continue to rise. The use of oil

especially became much greater starting after World War II. It was

the availability of cheap oil that allowed the world economy to grow

again.

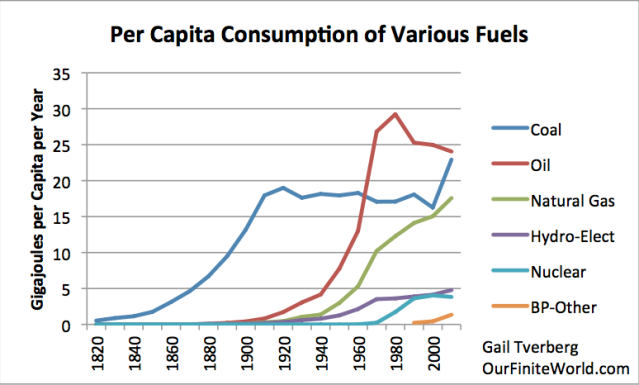

Figure

16. Per capita energy consumption by fuel, separately for several

energy sources, using the same data as in Figure 1.

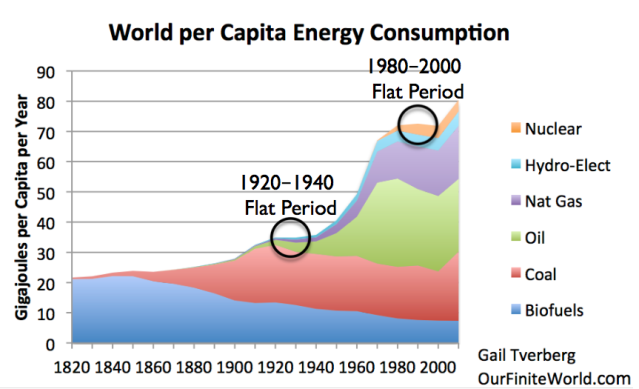

The

stimulus of all the debt-enabled spending for World War II seems to

have been what finally encouraged the production of the oil needed to

pull the world economy out of the problems it was having. GDP and

Disposable Personal Income could again rise (Figure 17.)

Figure

17. Comparison of 3-year average change in disposable personal

income with 3-year change average in GDP, based on US BEA Tables

1.1.5 and 2.1.

Furthermore,

total per capita energy consumption began to rise, with growing oil

consumption (Figure 1). This growth in energy consumption per capita

seems to be what allows the world economy to row.

I

might note that there is one other exceptional period: 1980 to 2000.

Space does not allow for an explanation of the situation here, but

falling per capita energy consumption seems to have led to the

collapse of the former Soviet Union in 1991. This was a different

situation, caused by lower

oil consumption related to efficiency gains.

This was a situation of an oil producer being “squeezed out”

because additional oil was not needed at that time. This is an

example of a different type of economic disruption caused by flat per

capita energy consumption.

Figure

18. World per Capita Energy Consumption with two circles relating to

flat consumption. World Energy Consumption by Source, based on

Vaclav Smil estimates from Energy Transitions: History, Requirements

and Prospects (Appendix) together with BP Statistical Data for 1965

and subsequent, divided by population estimates by Angus Maddison.

Conclusion

There

have been many views put forth about what caused the Depression of

the 1930s. To my knowledge, no one has put forth the explanation

that the

Depression was caused by Peak Coal in 1913 in UK, and a lack of other

energy supplies that were growing rapidly enough to make up for this

loss. As UK “exported” this problem around the world, it led to

greater wage disparity. US farmers were especially affected; their

incomes often dropped below the level needed for families to buy the

necessities of life.

The

issue, as I have discussed in previous posts, is a physics issue.

Creating GDP requires energy; when not enough energy (often fossil

fuels) is available, the economy tends to “freeze out” the most

vulnerable. Often, it does this by increased wage disparity. The

people at the top of the hierarchy still have plenty. It is the

people at the bottom who find themselves purchasing less and less.

Because there are so many people at the bottom of the hierarchy,

their lower purchasing power tends to pull the system down.

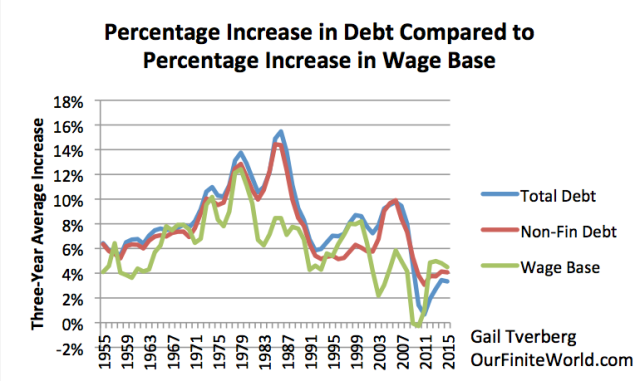

In

the past, the way to get around inadequate wages for those at the

bottom of the hierarchy has been to issue more debt. Some of this

debt helps add more wages for non-elite workers, so helps fix the

affordability problem.

Figure

19. Three-year average percent increase in debt compared to three

year average percent increase in non-government wages, including

proprietors’ income, which I call my wage base.

At

this time, we seem to be reaching the point where, even with more

debt, we are running out of cheap energy to add to the system. When

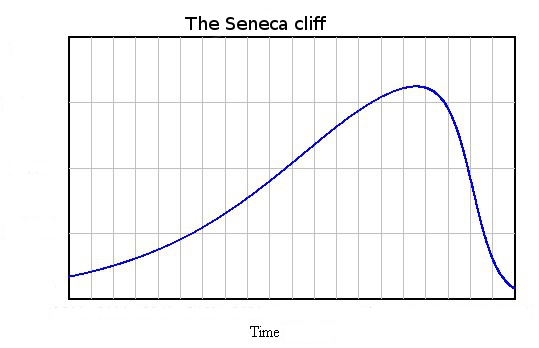

this happens, the economic system seems more prone to fracture.

Ugo Bardi calls the situation “reaching the inflection point in a

Seneca Cliff.”

We

were very close to the inflection point in the 1930s. We were very

close to that point in 2008. We seem to be getting close to that

point again now.

The

model of the 1930s gives us an indication regarding what to expect:

apparent surpluses of commodities of all types; commodity prices that

are too low; a lack of jobs, especially ones that pay an adequate

wage; collapsing financial institutions. This is close to the

opposite of what many people assume that peak oil will look like. But

it may be a better representation of what we really should expect.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.