Onrush of Second Monster Kelvin Wave Raises Specter of 2015 Super El Nino

9 April, 2015

And so it appears we are living in a time of Monster Kelvin Waves — powerful confluences of Pacific Ocean heat running just beneath the surface — bringing with them the potential for both record global heat spikes and strong, climate wracking El Nino events.

* * * * *

Last year, a powerful pulse of sub-surface heat called a Kelvin Wave rippled across the Equatorial Pacific. It shoved sub-surface temperature anomalies into an extreme range of 6 degrees Celsius above average at a depth of 90-130 meters over an equatorial zone stretching out for hundreds of miles. Overall, this heat surge pushed anomalies below the rippling waves of the vast Equatorial Pacific from New Guinea to the Central American Coastline above 1.8 degrees C hotter than average.

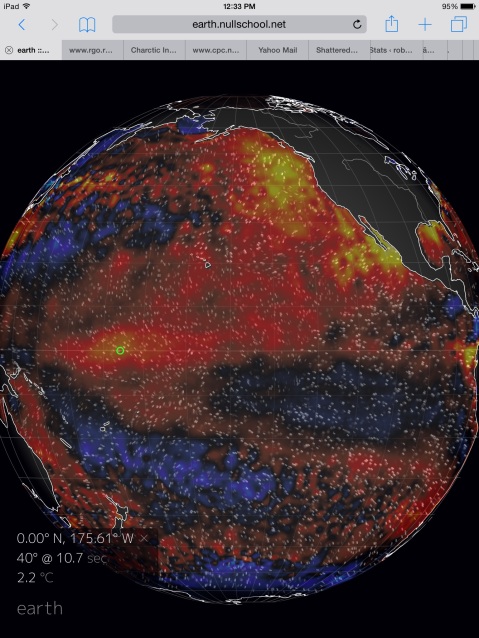

(Building heat in Pacific Equatorial Surface waters on April 9 of 2015 — a sign of a massive pulse of hotter than normal water running at about 100 meters depth. A heat pulse that may be setting in place conditions for a powerful El Nino later this year. Image source: Earth Nullschool. Data Source: Global Forecast System Model.)

This immense heat pulse was enough to shove the equatorial region inexorably toward El Nino status. By September, mid-ocean values were hot enough to have reached the critical threshold of 0.5 C above surface value average. Perhaps more importantly, the Winter/Spring 2014 Kelvin Wave also contributed to record positive PDO values for the Pacific by December of 2014. A surface heat departure that was unprecedented to modern climates. Block-busting ocean warmth that almost certainly spurred 2014 global atmospheric temperatures to new all-time record highs in the current age of human warming.

Monster Kelvin Wave Redux

Now, a second, and equally strong monster Kelvin Wave is again rippling across the Pacific Ocean subsurface zone. A powerful pulse of heat that will reinforce the current weak, mid-ocean El Nino, lend energy to ridiculously warm Pacific Ocean sea surface states, and pave the way for a long-duration equatorial heat spike.

(Monster Kelvin Wave Redux. A second powerful Kelvin Wave is surging across the Pacific Equatorial Subsurface zones, strengthing prospects for both a continued El Nino and for a record hot year in 2015. Image source: NOAA/CPC.)

As we can see in the NOAA CPC rendering above, the current Kelvin Wave is a massive and extraordinarily warm beast of a thing. It encompasses most of the thousands-miles broad Equatorial Pacific with its hottest zone peaking at 5-6 degrees Celsius above average temperatures — a region that stretches from near the Date Line all the way to just west of Central America. At +1.75 C for the entire below-surface equatorial region, the current Kelvin Wave is already approaching last year’s peak values. Values it may well exceed in the coming days.

Overall, the current Kelvin Wave seems to have more connection to the surface environment than last year’s powerful surge. A massive plug of Pacific Ocean heat readying to belch back into the atmosphere.

Some Models Show Potential For Super El Nino

Already, NOAA is upping its forecast chances for El Nino to continue through summer to 70 percent and is placing a greater than 60 percent chance that El Nino will stretch on through late autumn. An upshot from earlier predictions made just a little more than a month ago that El Nino formation for 2015 remained uncertain. Now, we have a rather high certainty that El Nino will continue throughout at least the next 4-6 months.

But perhaps more concerning is the fact that a strong El Nino is again starting to show up in some of the long range models. NOAA’s CFS ensemble shows El Nino continuing to steadily strengthen throughout 2015 reaching overall Nino 3.4 surface values above +2.1 C by October, November and December of this year:

(Top frame shows predicted sea surface temperature anomalies in the critical Nino 3.4 zone exceeding 2.2 C by late 2015. Such an event would be a monster to rival or possibly exceed 1998. The lower frame shows sea surface temperature departures for the entire globe. Note the seasonal spike of 2-3+ C above average for the Eastern Equatorial Pacific. Image Source: NOAA’s Seasonal Climate Forecast.)

The departures we see in this long range forecast are extraordinary — rivaling or possibly exceeding the intensity of the 1998 Super El Nino. An event of this kind would result in powerful ocean and atmospheric surface temperature spikes, catapulting us well beyond the climate range previously established by the 1998 event. Globally, we would be entering new, record hot territory, possibly approaching 1 C above 1880s values for the 2015-2016 period.

Troubling Situation With High Uncertainty

As such, we should consider this to be a troubling situation, in need of close, continued monitoring. To this point, it is worth noting that El Nino prediction during Spring is highly uncertain. Last year’s very strong Kelvin Wave also set off predictions for a moderate-to-strong El Nino event by summer-through-fall. Though El Nino did eventually emerge, it was weaker and later in coming than expected. Now, a new set of conditions is setting up similar, and perhaps, even more intense ocean and atmosphere heat potentials.

Though still uncertain, what we observe now are ocean conditions that raise potentials for both extreme El Nino and human-warming related weather. Powerful ocean heat pulses of the kind we observe now, when combined with an extraordinary human greenhouse gas heat forcing, also increases the likelihood of another record warm year. El Nino associated droughts and heatwaves — particularly for South America, India, Australia and Europe through Central Asia are at rising risk. In the event of mid-ocean El Nino, the risk increases that the 1200 year California drought will continue or even intensify. If the heat pulse shifts eastward, a switch to much heavier rainfall (potentially terribly heavy) could coincide with a breaking of the Ridiculously Resilient Ridge pattern that has warded moisture away from the US West Coast for nearly three years. Extra heat of this kind would also tend to enhance precipitation extremes — more rain when it does rain and far more intense drought in areas affected by heat and atmospheric ridging.

Given the patterns we have observed over the last year, we could expect worsening conditions for some regions (India, Australia, some sections of South America, Eastern Europe) and the potential for a shift from one extreme to the next for other regions (US West Coast). These potentials depend on the disposition and intensity of surface heat in the Pacific, which bears an even closer watch going forward.

Links:

NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center

NOAA’s April 9 El Nino Statement

NOAA’s Seasonal Climate Forecast

Earth Nullschool

Global Forecast System Model

Monster El Nino Emerging From the Depths?

Atmospheric Warming to Ramp up as PDO Swings Positive?

'Warm blob' in Pacific Ocean linked to weird weather across the US

Hickey

Read more at: http://phys.org/news/2015-04-blob-pacific-ocean-linked-weird.html#jCp

Hickey

Read more at: http://phys.org/news/2015-04-blob-pacific-ocean-linked-weird.html#jCp

annah Hickey

Read more at: http://phys.org/news/2015-04-blob-pacific-ocean-linked-weird.html#jCp

9

April, 2015

The

one common element in recent weather has been oddness. The West Coast

has been warm and parched; the East Coast has been cold and snowed

under. Fish are swimming into new waters, and hungry seals are

washing up on California beaches.

"In the fall of 2013 and early 2014 we started to notice a big, almost circular mass of water that just didn't cool off as much as it usually did, so by spring of 2014 it was warmer than we had ever seen it for that time of year," said Nick Bond, a climate scientist at the UW-based Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean, a joint research center of the UW and the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Bond coined the term "the blob" last June in his monthly newsletter as Washington's state climatologist. He said the huge patch of water - 1,000 miles in each direction and 300 feet deep - had contributed to Washington's mild 2014 winter and might signal a warmer summer.

Ten months later, the blob is still off our shores, now squished up against the coast and extending about 1,000 miles offshore from Mexico up through Alaska, with water about 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than normal. Bond says all the models point to it continuing through the end of this year.

The new study explores the blob's origins. It finds that it relates to a persistent high-pressure ridge that caused a calmer ocean during the past two winters, so less heat was lost to cold air above. The warmer temperatures we see now aren't due to more heating, but less winter cooling.

Co-authors on the paper are Meghan Cronin at NOAA in Seattle and a UW affiliate professor of oceanography, Nate Mantua at NOAA in Santa Cruz and Howard Freeland at Canada's Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

The authors look at how the blob is affecting West Coast marine life. They find fish sightings in unusual places, supporting recent reports that West Coast marine ecosystems are suffering and the food web is being disrupted by warm, less nutrient-rich Pacific Ocean water.

The blob is just one element of a broader pattern in the Pacific Ocean whose influence reaches much further - possibly to include two bone-chilling winters in the Eastern U.S.

A study in the same journal by Dennis Hartmann, a UW professor of atmospheric sciences, looks at the Pacific Ocean's relationship to the cold 2013-14 winter in the central and eastern United States.

Despite all the talk about the "polar vortex," Hartmann argues we need to look south to understand why so much cold air went shooting down into Chicago and Boston.

His study shows a decadal-scale pattern in the tropical Pacific Ocean linked with changes in the North Pacific, called the North Pacific mode, that sent atmospheric waves snaking along the globe to bring warm and dry air to the West Coast and very cold, wet air to the central and eastern states.

"Lately this mode seems to have emerged as second to the El Niño Southern Oscillation in terms of driving the long-term variability, especially over North America," Hartmann said.

In a blog post last month, Hartmann focused on the more recent winter of 2014-15 and argues that, once again, the root cause was surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific.

That pattern, which also causes the blob, seems to have become stronger since about 1980 and lately has elbowed out the Pacific Decadal Oscillation to become second only to El Niño in its influence on global weather patterns.

"It's an interesting question if that's just natural variability happening or if there's something changing about how the Pacific Ocean decadal variability behaves," Hartmann said. "I don't think we know the answer. Maybe it will go away quickly and we won't talk about it anymore, but if it persists for a third year, then we'll know something really unusual is going on."

Bond says that although the blob does not seem to be caused by climate change, it has many of the same effects for West Coast weather.

"This is a taste of what the ocean will be like in future decades," Bond said. "It wasn't caused by global warming, but it's producing conditions that we think are going to be more common with global warming."

More information: Causes and Impacts of the 2014 Warm Anomaly in the NE Pacific, DOI: 10.1002/2015GL063306

Journal reference: Geophysical Research Letters

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.