From Record Floods to Drought in Three Months: Unusually Hot, Dry Conditions Blanket South

4

December, 2017

Back

during late August of 2017, Hurricane

Harvey dumped as much as 60.48 inches of rain over southeast Texas.

Harvey was the wettest tropical cyclone on record ever to strike the

U.S. — burying Houston and the surrounding region under multiple

feet of water, resulting in the loss of 91 souls, and inflicting more

than 198 billion dollars in damages.

Harvey

was the costliest natural disaster ever to strike the U.S. Its

tropical rains were the heaviest ever seen since we started keeping a

record. But strangely, almost inexplicably, just a little more than

three months later, the region of southeast Texas is now facing

moderate drought conditions.

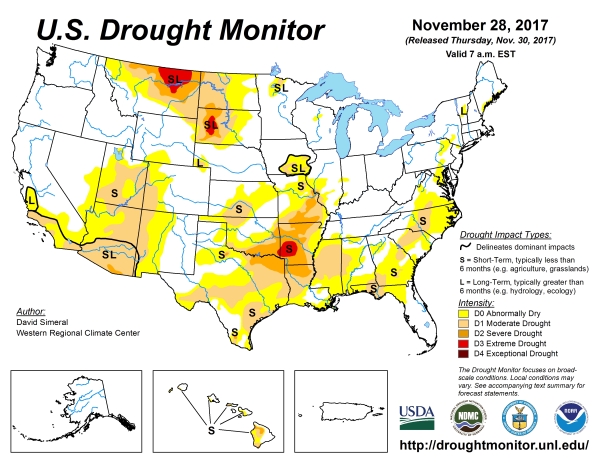

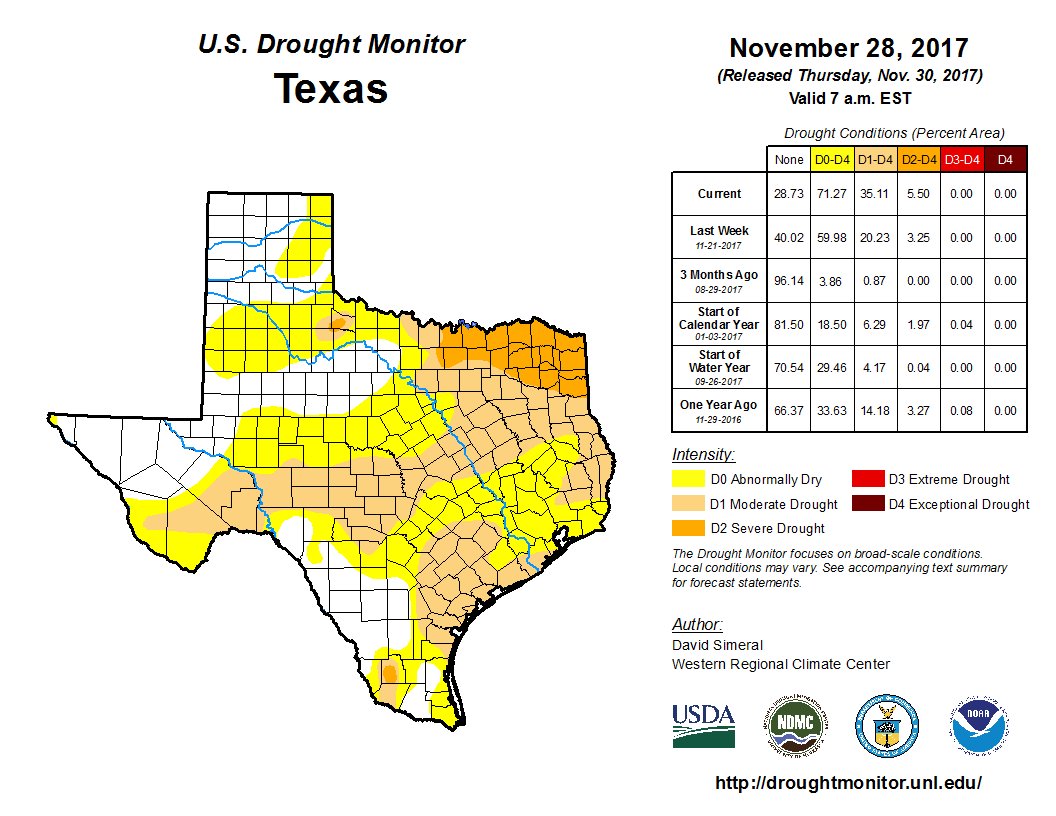

(Just

three months after Harvey’s record rains, Southeast Texas is

experiencing drought. No, this is not quite normal despite a mild La

Nina exerting a drying influence. Image source:U.S.

Drought Monitor. Hat

tip to Eric Holthaus.)

How

did this happen? How did so much water disappear so soon? How could

an instance of one of the most severe floods due to rainfall the U.S.

has ever experienced turn so hard back to drought in so short a time?

In

a sentence — climate change appears to be amplifying a natural

switch to warmer, drier weather conditions associated with La Nina.

Climate

change, by adding heat to the Earth’s atmosphere and oceans

fundamentally changes the flow of moisture between the air, the ocean

and the land. It increases the intensity of both evaporation and

precipitation. But this increase isn’t even. It is more likely to

come about in extreme events. In

other words, climate change increases the likelihood of both more

extreme drought and more extreme rainfall.

Of

course, climate change does not exist in a vacuum. Base weather and

climate conditions influence climate change’s impact. At present,

with La Nina emerging in the Pacific, the tendency for the southern

U.S. would be to experience warmer and drier conditions. But in a

normal climate, these conditions would tend to be milder. In the

present climate — warmed up by fossil fuel burning — the tendency

is, moreso, to turn toward an extreme. In this case, an extreme on

the hot and dry end of the climate spectrum.

For

the region of Southeast Texas flooded so recently by Harvey’s

record rains, it means that a turn from far too wet to rather too dry

took just a little more than 3 months.

(Both

temperature and moisture took a very hard turn over the past 30 days.

Such extremely warm and dry conditions increase the likelihood of

flash drought. A

climate feature that has become far more frequent as the Earth has

warmed.

Image source: NOAA.)

South

Texas, however, is just one pin in the map of a larger trend toward

drought that is now blanketing the South. Over the past month,

precipitation levels were less than 50 percent of normal amounts in

most locations with a broad region over the south and west

experiencing less than 10 percent of the normal allotment of

moisture. Meanwhile, 90-day

precipitation averages are also much lower than normal across the

South.

Precipitation

is a primary factor determining drought. But temperature can mitigate

or worsen drought conditions. Higher temperatures cause swifter

evaporation — driving moisture out of soils at a faster rate. And

average temperatures across the south have been quite warm

recently. With

one month averages ranging from 1 C above normal over most of the

south to a whopping 8 C above normal over parts of New Mexico.

As with lower than normal precipitation, higher than normal

temperatures have also extended into

the past 90 day period across most of the South.

(Moderate

drought conditions are widespread as severe to extreme drought is

starting to crop up in the South-Central U.S. With La Nina likely to

continue through winter and with global temperatures in the range of

1.1 to 1.2 C above pre-industrial averages, there is risk that

conditions will intensify. Image source: U.S.

Drought Monitor.)

The

upshot is that moderate drought is taking hold, not just in southeast

Texas, but across the southwest, the southeast, and south-central

U.S. Severe to extreme drought has also already blossomed from

northern Texas and Louisiana through Oklahoma, Arkansas and Missouri.

This is relatively early to see such a sharp turn, especially

considering the fact that La Nina conditions have only lasted for a

short while and have, so far, been

rather mild on the scale of that particular climate event.

Furthermore,

like Texas, many of these drying regions experienced extreme rainfall

events during spring and summer. Such events, however, were not

enough to stave off a hard shift to drought in a world in which

human-caused climate change is now driving both droughts and more

extreme rainfall events to rising intensity.

(Predicted

temperature and precipitation variance from normal over next three

months. Climate change is likely to enhance this variability related

feature. Image source: NOAA.)

With

La Nina likely to remain in place throughout winter,

the typical climate tendency would be for continued above average

temperatures across the south and continued below average rainfall

for the same region. Present human-caused global warming through

fossil fuel burning in

the range of 1.1 to 1.2 C above pre-industrial averages will

tend to continue to amplify this warm, dry end of the natural

variability cycle (for the southern U.S.).

In

other words, there is not insignificant risk that the hard turn away

from record wet conditions in the South will continue and that severe

to very severe drought conditions will tend to spring up and expand.

RELATED

STATEMENTS:

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.