California will burn until it rains — and climate change may keep future rains away

Dry

weather looms ahead as fires rage across Southern California

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/57880155/886767680.jpg.0.jpg)

6

December, 2017

Wildfires

are spreading unchecked across Southern California, adding more

infernos to the state’s worst

fire season on record. A warm, dry fall in Southern California

and strong offshore winds combined to create dangerous fire

conditions that

will probably get worse. As the winds

continue to blow, a dome of warm, high-pressure air is forming

over the West Coast that could keep California dry and flammable for

weeks to come.

The

largest fire burning in Southern California started in the foothills

of Ventura County on Monday evening. Called the “Thomas fire,” it

spread overnight to burn more

than 65,000acres, jumped the 101 freeway, and was stopped only by

the Pacific Ocean, the LA

Timesreports.

Four more fires are raging from

San Bernardino to Santa Clarita.

Hot,

dry winds blowing

up to 70 miles per hour across Southern California are

fanning the flames, but those

aren’t unusual for December, says Daniel

Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California Los

Angeles and writer of the Weather

West blog.

Called the Santa Ana winds, these southern counterparts to Northern

California’s Diablo winds tend to kick up during the fall and

continue through the winter.

But

something unusual is happening:

Southern California’s warm winter dry spell, Swain says. “By this

time of year, usually, there’s been some rain that’s wetted

things down,” he says in a telephone interview, speaking over the

Santa Ana winds howling in the background. “It’s just as dry as

it was in the summer months.”

California

gets most of its rain between October and May from storms that roll

in from the Pacific, riding a highway of strong winds in

the upper atmosphere called the jet stream. By now, LA

should have been sprinkled by about two inches of rain, National

Weather Service meteorologist John Dumas told the LA

Times.

But so far it’s only seen about 5 percent of that, amounting

to about

one-tenth of an inch. Burbank, California, has seen even less,

says National Weather Service meteorologist David Sweet. Despite the

rain that’s been showering Northern California, the

bottom part of the state is abnormally dry; certain areas are

even experiencing a moderate drought. “We’re quite parched,”

Sweet says.

- Pinned TweetSpecial post on the Weather West blog: deep dive into our new research on the #RidiculouslyResilientRidge and the North American Temperature Dipole. Focuses on work by @ClimateChirper @danethanNU @jsmankin @Weather_West (and others). #CAwx #CAdrought

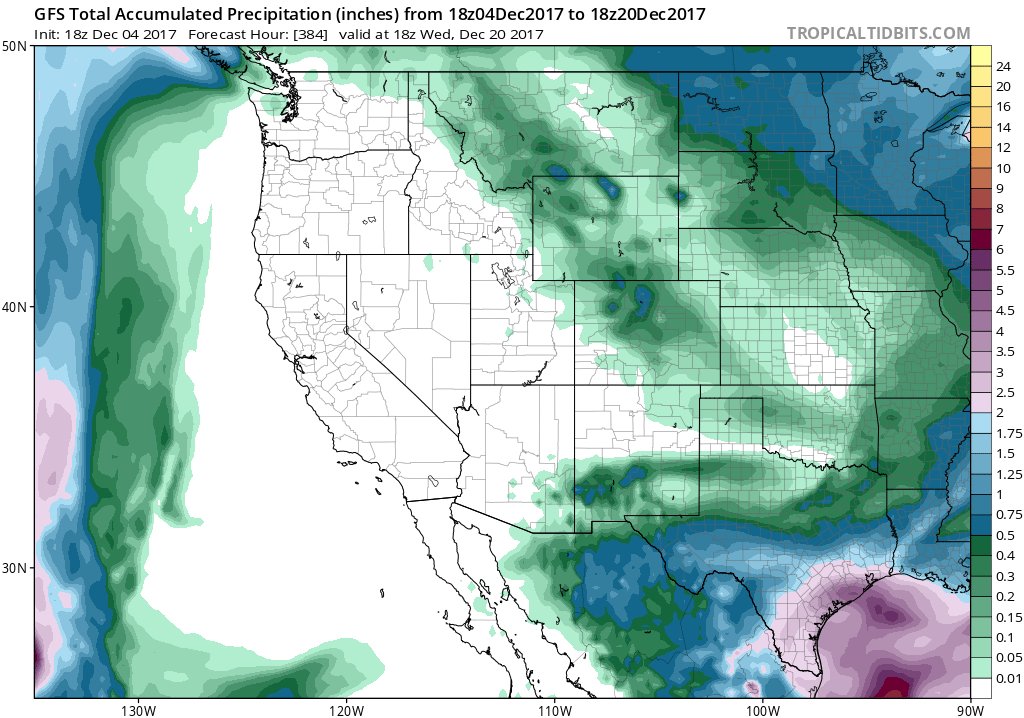

Storms

in the jet stream can get diverted by high-pressure bubbles of warm

air. A version of this phenomenon called an "atmospheric ridge"

is to blame for Southern California's current dry spell. And even

even bigger one has started forming along the entire West Coast of

the US that could shunt rainfall into Canada or Alaska, Swain

writes. “We were dry before and now the prospects for rain look

even less likely because of the size of this thing,” Sweet says.

This

is the same atmospheric phenomenon that squatted over the state for

three winters in a row during California’s record-setting,

five-year drought. “The real question is how long it persists,”

Swains says. During the drought, these ridges lasted for months at a

time — but we don’t know what’s in store for this new one. Even

worse news: these atmospheric ridges are getting more common —

possibly thanks to human-caused global warming, Swain and his

colleagues reported

in a 2016 study.

And

they could become even more frequent

in the future as the polar ice melts, new research says. Scientists

led by Ivana

Cvijanovic at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory modeled

how dwindling Arctic sea ice could affect the global climate over the

coming decades. They found that as the sea ice melts, the Arctic

warms — starting a chain reaction that ultimately helps these

atmospheric ridges form over the North Pacific, blocking rain from

falling on California. That doesn’t just make drought more common,

it’s also possible that it could also make fire seasons last

longer.

The

findings, described in a new study published Tuesday in the

journal Nature

Communications,

are a hint of what’s to come — but they’re not a prediction of

the future, Cvijanovic cautions. Other shifts in air pollution,

greenhouse gasses, and even volcanic activity over the coming decades

could also change how much rain falls on California. (In

fact, another

recent study suggests climate change could make California

wetter.)

What’s

clear for now is that the dry, windy weather forecast for Southern

California means that the firefighters struggling to stop the flames

have a long battle ahead of them. “The fire season in Southern

California stops when you get enough rain that everything gets wet

and turns plump and green,” says Bill Stewart, a forestry

specialist at UC Berkeley. “That’s the only thing that’s going

to change the system down there.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.