Medics in Covid hotspots are just days away from having to make 'horrendous choices' over who they can treat and who is left to die, a consultant warned last night.

England's hospitals are now busier than they were during the darkest days of the spring, with record coronavirus admissions forcing ambulances to wait outside crowded NHS facilities and many intensive care units operating well over their capacity.

It emerged certain London ICUs have asked major hospitals in Yorkshire, more than 150 miles to the north, if they will agree to take some patients.

With beds, staff and equipment all running low, consultant anaesthetist Dr Claudia Paoloni warned the situation was just days away from reaching the point where care would be rationed.

Dr Paoloni, president of the Hospital Consultants and Specialists Association, told The Guardian: 'Our NHS just doesn't have the beds to cope. Some areas will be overwhelmed in days. If ventilation capacity is exceeded, horrendous choices will have to be made over those who live and die.'

She added that other life determining choices will also have to be made, including which patients to admit to intensive care and how long to continue treatments on patients who appear to be making no progress, if for example a patient with better chances of survival needs the haemodialysis machine they are using.

Look at this!

“Please don't mix with other households. Not even with

your families. Not your friends. Not your mum or dad.

Any human contact will spread this virus, especially the

new mutant strain”

This article tells a different story from what is being spun in the media

ICU Occupancy in English

Hospitals No Higher Than

Last December

29 December, 2020

The media is full of alarming reports of NHS hospitals being on the brink of armageddon, such is the surge in coronavirus patients. “As we head into the new year we are seeing a real rise in the pressure on NHS services, particularly across London and the south-east,” Saffron Cordery, the Deputy Chief Executive of NHS Providers told the Guardian.

A letter from NHS chiefs sent to the chief executives of all NHS trust and foundation trusts on December 23rd contained this alarming paragraph:

With COVID-19 inpatient numbers rising in almost all parts of the country, and the new risk presented by the variant strain of the virus, you should continue to plan on the basis that we will remain in a level 4 incident for at least the rest of this financial year and NHS trusts should continue to safely mobilise all of their available surge capacity over the coming weeks. This should include maximising use of the independent sector, providing mutual aid, making use of specialist hospitals and hubs to protect urgent cancer and elective activity and planning for use of funded additional facilities such as the Nightingale hospitals, Seacole services and other community capacity. Timely and safe discharge should be prioritised, including making full use of hospices. Support for staff over this period will need to remain at the heart of our response, particularly as flexible redeployment may again be required.

And the Independent reports that the London Ambulance Service has issued a warning saying it can no longer guarantee an ambulance will turn up if women giving birth at home require emergency care.

Sounds like a major crisis, right? Better move the rest of England into Tier 4, make mask-wearing mandatory in all settings and close schools until Easter.

Or is it?

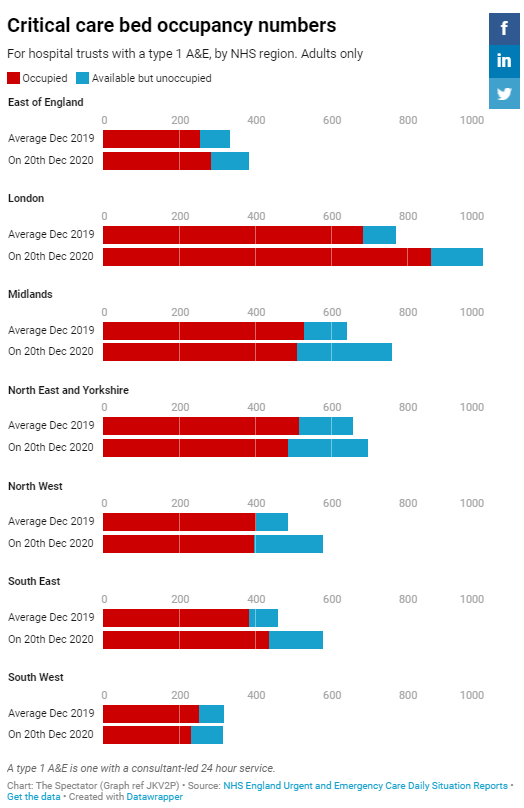

If you look at ICU occupancy in NHS hospitals across England on December 20th it was lower than the December average in 2019 in most of the country – and it’s worth remembering that the 2019-20 flu season was unusually mild.

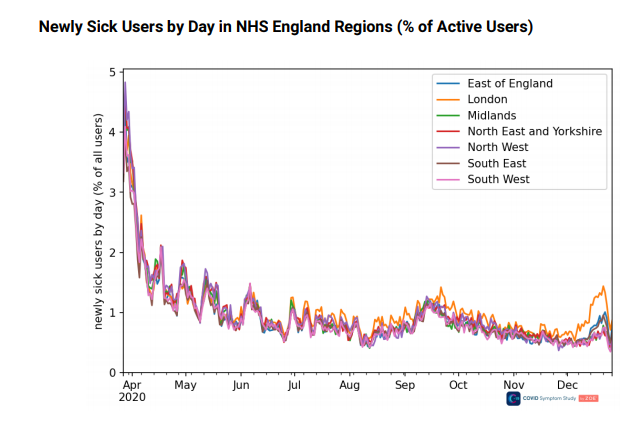

Admittedly, the total number of ICU beds occupied in London on Dec 20th was quite a bit higher than the average for December 2019, but according to the ZOE app daily symptomatic cases in London are falling. The ZOE data in the graph below shows rising and falling daily symptomatic cases up to December 27th.

It’s also worth bearing in mind that there are more ICU beds this year than last year, so if you calculate the percentage of ICU beds occupied in NHS hospitals across England and compare that to the average percentage in December 2019 the picture looks even less bleak. In every region, including London, the percentage of ICU beds occupied at the moment is lower than it was this time last year.

East:

Dec 2019 average: 76.3%

On Dec 20th 2020: 74.0%London:

Dec 2019 average: 88.7%

On Dec 20th 2020: 86.3%Midlands:

Dec 2019 average: 82.2%

On Dec 20th 2020: 67.0%North East and Yorkshire:

Dec 2019 average: 78.4%

On Dec 20th 2020: 69.8%North West:

Dec 2019 average: 82.6%

On Dec 20th 2020: 68.7%South East:

Dec 2019 average: 83.7%

On Dec 20th 2020: 75.4%South West:

Dec 2019 average: 79.5%

On Dec 20th 2020: 73.3%

I’m not suggesting that NHS hospitals aren’t under pressure – nor even that they aren’t under more pressure than they were this time last year. But the issue isn’t a lack of ICU beds and it doesn’t appear to be a surging number of patients admitted to ICU beds with COVID-19. After all, if those numbers were surging on top of the usual December admissions for respiratory diseases you’d expect the total number of ICU beds occupied to be much higher this year than last and, as you can see from the Spectator data, the totals are lower in four of England’s seven NHS regions.

The reason for the crisis – if indeed there is a crisis – must lie elsewhere.

My money’s on a combination of higher-than-average staff absences and poor management. Disappointing, considering the NHS has had over six months to prepare for this “crisis”.

Lockdowns Pose Greatest Threat to Mental Health Since Second World War

According to the country’s leading psychiatrist, the ongoing restrictions pose the greatest threat to mental health since the Second World War. The Guardian has more.

Dr Adrian James, the president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, said a combination of the disease, its social consequences and the economic fallout were having a profound effect on mental health that would continue long after the epidemic is reined in.

As many as 10 million people, including 1.5 million children, are thought to need new or additional mental health support as a direct result of the crisis.

“This is going to have a profound effect on mental health,” James said. “It is probably the biggest hit to mental health since the Second World War. It doesn’t stop when the virus is under control and there are few people in hospital. You’ve got to fund the long-term consequences.”

Demand for mental health services dropped at the start of the pandemic as people stayed away from GP surgeries and hospitals, or thought treatment was unavailable. But the dip was followed by a surge in people seeking help that shows no sign of abating.

Data from NHS Digital reveals that the number of people in contact with mental health services has never been higher, and some hospital trusts report that their mental health wards are at capacity. “The whole system is clearly under pressure,” James said.

Modelling by the Centre for Mental Health forecasts that as many as 10 million people will need new or additional mental health support as a direct result of the coronavirus epidemic. About 1.3 million people who have not had mental health problems before are expected to need treatment for moderate to severe anxiety, and 1.8 million treatment for moderate to severe depression, it found.

The overall figure includes 1.5 million children at risk of anxiety and depression brought about or aggravated by social isolation, quarantine or the hospitalisation or death of family members. The numbers may rise as the full impact becomes clear on Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities, care homes and people with disabilities.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.