How SAGE and the UK media created fear in the British public

27 June, 2020

COVID-19 started registering with most of the British public around late February and early March. Many were concerned but not particularly afraid. Only weeks later people were terrified to leave their homes or go near other human beings. How did such a dramatic shift in public perception happen so quickly?

In early March 2020, The Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) produced a document for the UK Government highlighting methods for rolling out new social distancing rules. There seemed to be some doubt as to whether the public would comply with the upcoming measures so SAGE outlined a methodology based on known psychological behavioural modification techniques.

SAGE is an advisory group to the UK government responsible for making sure decision makers have access to scientific advice. We are told that the advice provided by SAGE does not represent official government policy.

SAGE also relies on expert sub-groups for COVID-19 specific advice. These sub-groups include:

- NERVTAG: New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group

- SPI-M: Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Modelling

- SPI-B: Independent Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Behaviours

The identity of individual committee members themselves were initially kept secret, purportedly due to national security. Some names were eventually released, largely due to efforts by UK businessman Simon Dolan and his legal challenge campaign. Nevertheless, two members remain anonymous.

Psychological techniques for behavioural change

The document itself, titled Options for increasing adherence to social distancing measures, was drafted by SPI-B, the behavioural science sub-group for SAGE.

SPI-B highlighted nine broad ways of achieving behavioural change in the public:

- Education

- Persuasion

- Incentivisation

- Coercion

- Enablement

- Training

- Restriction

- Environmental restructuring

- Modelling

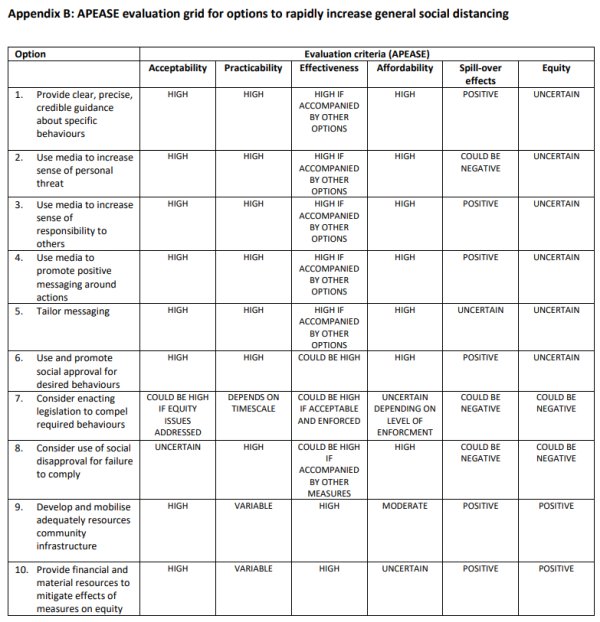

In the document, SPI-B focused on the methods most relevant to their stated goals and set out ten options that were evaluated on six criteria.

The six criteria, under the acronym APEASE, were:

- Acceptability

- Practicability

- Effectiveness

- Affordability

- Spill-over effects

- Equity

Government persuasion through fear

A key part of SPI-B’s behavioural change strategy that seems to have been adopted was to ‘persuade through fear.’ The Persuasion section of the document states:

A substantial number of people still do not feel sufficiently personally threatened.

Clearly, the psychologists felt that, as of late March, the public was still not afraid of COVID-19. It therefore suggested that the government increase the level of fear:

The perceived level of personal threat needs to be increased among those who are complacent, using hard-hitting emotional messaging.

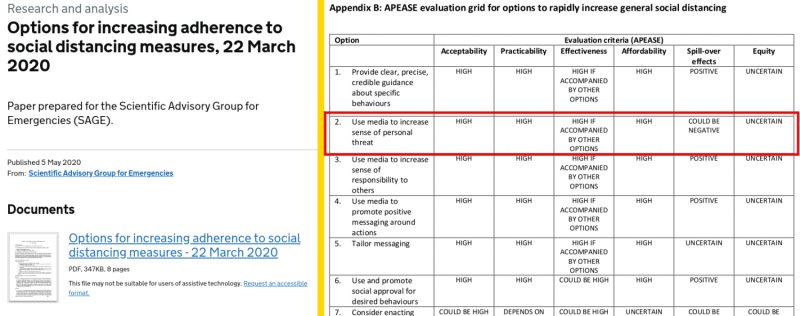

Appendix B of the document lists ten options that can be used to increase social distancing in the public. Option 2 advises:

Use media to increase sense of personal threat.

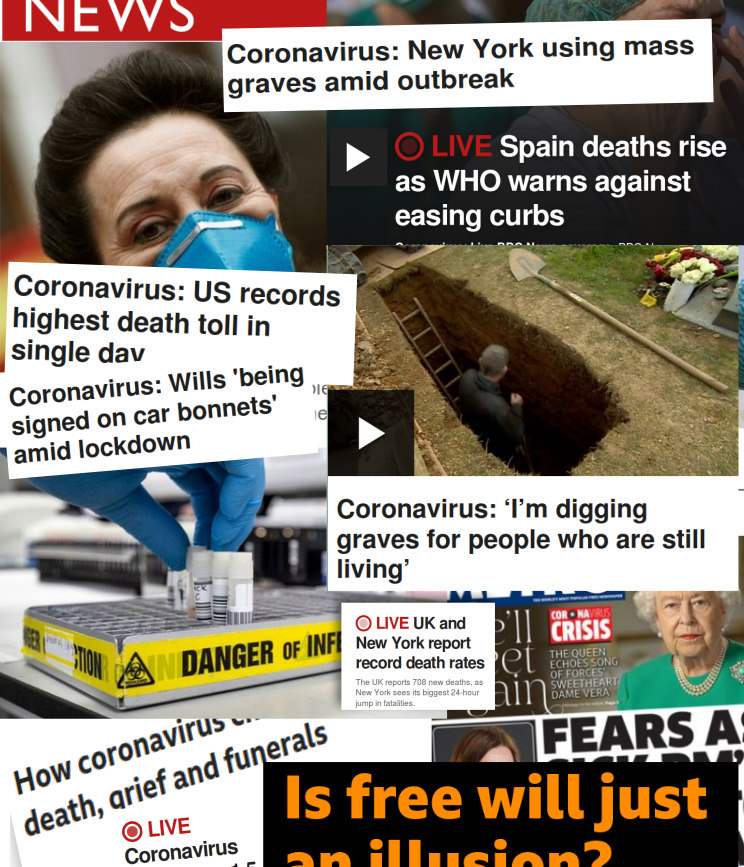

In hindsight, this explains the tone of government sponsored social media and physical billboard advertising campaigns that started appearing around April.

SPI-B recommendations to increase personal threat and use hard-hitting emotional messaging are on display with eerie imagery coupled with taglines such as:

- “Anyone can get it. Anyone can spread it.“

- “Don’t put your friends and family in danger.“

- “Stay home for your family. Don’t put their lives in danger.“

- “If you go out, you can spread it. People will die.“

The article compared hysterical BBC news headline from the first week of April 2020 with those from 2018, when mortality rates were peaking due to a bad flu season. It found no references to flu or excess mortality on the BBC home page during the 2018 peak. InProportion2 asked, “Do the headlines reflect the gravity of the situations in an equivalent way – or is additional fear being stirred up in 2020?“

Persuasion through shame and approval: Covidiots and heroes

SPI-B psychologists knew that fear on its own would not persuade everyone. Messaging needed to be tailored to take into account different ‘motivational levers.’

Some people will be more persuaded by appeals to play by the rules, some by duty to the community, and some to personal risk.

It therefore suggested using both social approval and disapproval, with compulsion (legislation) as a backup:

- Option 6: Use and promote social approval for desired behaviours

- Option 7: Consider enacting legislation to compel required behaviours

- Option 8: Consider use of social disapproval for failure to comply

We can see the obvious approval-disapproval dialectic with the ‘Heroes and Covidiots’ narrative that soon began to surface in the news. The term ‘Covidiot’ appeared around March with The Economist’s 1843 Magazine describing covidiots in this way:

Even in a pandemic, many of us are prone to judge others and find them wanting: the term “covidiot” describes any and every person behaving stupidly or irresponsibly as the epidemic spreads. Sometime in early March the word was born, and, almost as fast as the virus spread, so did instances of covidiotic behaviour.

Although it’s not clear how the term came about, it was quickly adopted in UK mainstream and social media. At the same time, we began seeing praise for heroes who ‘did the right thing’ by complying with the government measures.

The METRO article below shows all three options in play:

- Social approval: “These local heroes have been doing amazing things…”

- Social disapproval: “Lake District closed…because covidiots won’t stay away…”

- Compulsion: “Matt Hancock threatens to close beaches…”

An incentivised media

These psychological techniques would have been impossible to deploy on the public without a compliant media. How did the government convince the media to go along with the plan?

Increased UK government media spending

Digiday, a media and marketing industry publication, reported in April that the government is becoming UK news publishers’ most important client. In the 20 April 2020 article for Digiday, Lara O’Reilly wrote:

…the government is spending more than usual, judging by their bookings. The publishers also pointed out that the lack of activity from other advertisers in the current market means the government campaigns will have an outweighed share of voice compared with normal times.

During that period, the British public started seeing coverage across media outlets with the unified “In this together” messaging. O’Reilly pointed out that the campaign was worth £35 million over a three month period.

Last week, the government and newspaper industry launched a three-month advertising partnership dubbed “All in, all together.” The campaign — worth approximately £35 million ($44 million) for the full course, according to sources — kicked off on Apr. 17, with all the U.K.’s national and regional daily news brands running near-identical cover wraps and homepage takeovers, which carried the copy, “Stay at home for the NHS, your family, your neighbours, your nation the world and life itself.”

So, we ask again: how did the government convince the media to go along with the plan? The answer is simple and obvious: with lots of money.

Psychological techniques to change behaviour

We can see that the UK Government has a public document outlining psychological techniques to change the behaviour of the population. We see a unified mass-media campaign that falls in line with these techniques. We then see a dramatic shift in public perception and behaviour.

What else can we call this but ‘brainwashing’?

Despite the open nature of what has transpired, it seems to have gained little coverage in the media. This is of no surprise since it was clearly complicit in spreading fear in the public.

Download the document

The document is freely downloadable on the gov.uk website in a page titled, “Research and analysis – Options for increasing adherence to social distancing measures, 22 March 2020“.

We encourage you to read the document, compare it with your observations about how the government and media has acted, then make up your own mind.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.