There is a possibility that the series of intense Pacific cyclones we are experiencing at the moment will give momentum to the El Nino.

I

am watching Tropical Cyclone Pam as I type this and I believe that

more intense the El Nino the more extreme the weather and forcing

will be. Expect the worst from this very bad news that we have been

dreading but expecting.

--- Kevin Hester

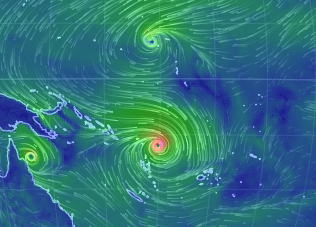

‘Twin’ Cyclones Could Jolt Weak El Nino

Weather

geeks have been fixated

this week on

an unusual meteorological phenomenon over the Pacific Ocean: Two

tropical cyclones are spinning directly across the equator from each

other.

13

March, 2015

But

these “twin” cyclones aren’t just a satellite spectacle, they

could give a jolt to the El Niño that was officially declared by

U.S. forecasters last week after months of sitting on the fence. This

El Niño is a weak one, expected to have little impact on weather in

the U.S. The two storms that could provide a boost, however, are

Cyclone Pam, churning over the South Pacific at about 14 degrees

south latitude, threatening the islands of Vanuatu and Fiji with

strong, damaging winds and storm surge, and Tropical Depression 3 (or

Bavi), spinning over the northern Pacific near 10 degrees north

latitude heading towards Guam.

Together,

the cyclones and El Niño illustrate the interplay between short-term

weather and longer-term climate cycles, in this case potentially

reinforcing each other. It is unclear, though, whether the cyclones

caused a westerly wind burst ramping up the El Niño, or if it was

the El Niño pattern that spawned the cyclones.

El

Niño is a climate condition marked by unusually warm ocean waters in

parts of the tropical Pacific, but it has impacts on weather all over

the globe. By influencing atmospheric circulation, a strong El Niño

can bring unsusually wet weather to the southern portions of the U.S.

in the winter months, as well as drought to places like Australia and

Brazil. It also tends to tamp down hurricane formation in the

Atlantic Ocean, while amping up storms in parts of the Pacific. The

weather connections are less strong in spring, but if this El Niño

strengthens enough over the spring and summer, it could have

ramifications next winter.

Where

the two cyclones come in is the winds associated with an El Niño.

Normally, the tropical Pacific features a pool of warm water in the

west and cooler temperatures to the east, where cold waters well up

from deep off the coast of South America. The prevailing easterly

trade winds keep this temperature pattern in place. When an El Niño

occurs, the winds slacken and can even reverse to blow from the west.

That sends the warm waters spilling eastward, the hallmark of an El

Niño. (When a La Niña occurs, the easterlies grow stronger and

intensify the east-west temperature contrast.)

Bavi,

because it is in the Northern Hemisphere, rotates counterclockwise,

while Pam, rotates clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. In the

portions of the storms nearest the equator, the winds in both storms

are from the west.

“We

have an impressive westerly wind burst on the equator right now,”

Michelle L’Heureux, an El Niño forecaster with the National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said.

“The

winds are certainly tied in with these twin cyclones straddling the

equator.”

Those

westerly winds could help push the warm waters on the western side of

the basin further east and strengthen what is right now only a very

weak El Niño.

The

El Niño forecasters expected the increase in westerly winds

according to their models and it is “something we like to see when

we're saying an El Niño is in place and forecasted to continue,”

L’Heureux said.

What’s

hard to determine is whether the cyclones created the wind burst or

the other way around, as westerlies are also conducive to cyclone

formation in that area. Both could also be linked to a climate

pattern called the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO), which features

alternating areas of enhanced and suppressed rainfall that move from

west to east across the globe. When enhanced rainfall is over the

western Pacific, it tends to whip up the westerlies that can feed

cyclones and the El Niño. And this round of MJO could be

record-breaking.

But

it’s hard to predict how big an impact this push of winds will have

on the El Niño.

“How

much this westerly wind burst will energize El Niño is the big

question mark,” L’Heureux said.

Forecasters

are wary of a repeat of last year when a relatively strong MJO and a

very strong surge of warm waters, called a Kelvin wave, had some

predicting a repeat of the monster El Niño of 1997-1998. Then the

event fizzled.

“It's

still March, [and] as we know from last year, Kelvin waves are not a

slam-dunk predictor of [El Niño],” L’Heureux noted.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.