There's

some really intense melting in the Arctic right now

14

June, 2019

Records

are falling at the top of the world.

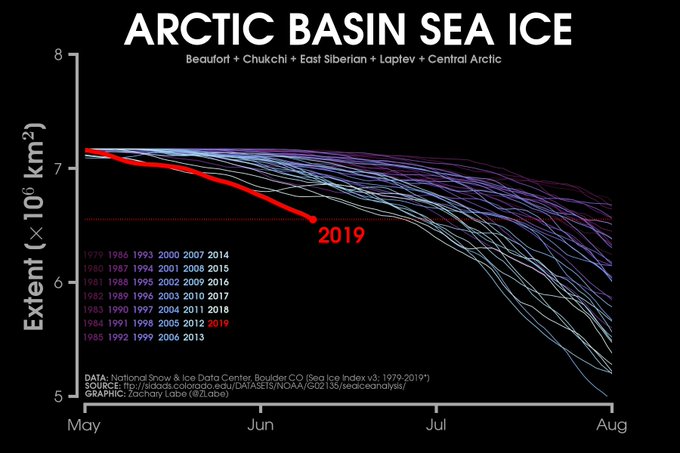

The

Arctic summer has a long way to go, but already sea ice levels over

great swathes of the sprawling Arctic ocean are at historic lows (in

the 40-year-long satellite record) for this time of year. The most

striking declines are in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas, located above

Alaska.

The

melt is exceptional, but right in line with accelerating melting

trends occurring as the

Arctic warms.

"Every

year we smash a record that we’re shocked at," said Jeremy

Mathis, a longtime Arctic researcher and a current board director at

the National Academies of Sciences.

By

the end of May, Arctic sea ice overall was vastly diminished, running

some 436,000

square miles below average. Now, the downward trend continues,

with the lowest

sea ice on record for mid-June.

We

should get used to these Arctic records, emphasized Mathis. "The

extraordinary change is a given," he said. "The Arctic is

superseding any projection we had for how quickly sea ice was going

to go away."

The

climate regime in the Arctic has changed sharply over the last few

decades. The Arctic was once blanketed with older, thicker ice. But

now the ice

is younger, thinner, and easily melted.

"This

is due to the long-term warming of the Arctic," said Zack Labe,

a climate scientist and PhD candidate at the University of

California, Irvine. "Air temperatures are now rising at more

than twice the rate of the global mean temperature — a phenomenon

known as 'Arctic Amplification'."

This

warm air means thinner and less hardy ice that's more susceptible to

melt during the summer, noted Labe.

And

with warmer air temperatures comes warmer oceans. The Arctic suffers

from a vicious feedback loop, wherein the bright, reflective ice

melts, and then more of the dark ocean absorbs sunlight. This drives

even more melting.

And

the oceans in large parts of the Arctic are indeed warmer than usual,

said Lars Kaleschke, a sea ice researcher at the Alfred Wegener

Institute for Polar and Marine Research. Kaleschke, who has been

watching the recent melting with "great interest," noted

that the waters in the Pacific Arctic and parts of the inner Arctic

are warmer than average. The ice is thinner there, too.

"In

consequence, the thinner ice now retreats much faster than usual,"

said Kaleschke.

For

the many of us viewing the melting Arctic on

satellite images from thousands of miles away, the rate of

change in the high north can be difficult to grasp. But not for

scientists like Mathis, who have traveled through these icy oceans.

"I’m

losing the ability to communicate the magnitude [of change],"

said Mathis. "I’m running out of adjectives to describe the

scope of change we’re seeing."

Though

the longer term melting trends are unmistakable, in the shorter term,

like this summer, Labe noted that cooler weather patterns can still

swoop in and potentially chill the region. Although ice is now at

record lows in many places — and overall is currently at the lowest

point in the satellite record — this year might not necessarily end

up breaking the all-time record low, set in 2012 at summer's end.

Regardless,

the big picture is clear. "The 12 lowest extents in the

satellite record have occurred in the last 12 years," the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noted

in 2018.

This

means a melting Arctic that's opening

up for more shipping and a militarization of the region from

the likes of Russia and China, explained Mathis. There's strong

evidence that a warmer Arctic also perturbs

global weather patterns and stokes weather extremes

thousands of miles away, in heavily populated areas.

IMAGE: NATIONAL SNOW AND ICE DATA CENTER

The

difference today, compared to the last hundreds of thousands of

years, comes down to the heat-trapping gas carbon dioxide saturating

the atmosphere, noted Mathis. Atmospheric carbon dioxide

concentrations are now accelerating at geologically

and historically unprecedented rates.

Even

if global civilization is able to slash

carbon emissions and curb temperatures at levels that would

avoid the worst

consequences of climate change, the exceptionally warmed Arctic

will still feel the heat.

"Regardless

of any mitigating efforts, the Arctic is going to be a fundamentally

different place," said Mathis.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.