Not Even the Briefest of Pauses for Human-Forced Global Warming — Oceans During 2017 Were the Hottest on Record

26

January, 2018

Where

does most of the heat trapped by human fossil fuel and other

greenhouse gas emissions ultimately end up? Given our fixation

on global surface temperatures, many people would say ‘the

atmosphere.’ But this answer is incorrect. The vast majority ends

up in the world ocean.

The

world ocean system is the largest heat sink on our planet’s

surface. This is due to the fact that liquid water contained in the

oceans both has a far greater mass and overall heat

capacity than

the atmosphere. Just a fraction — less than 1/30th of the heat

trapped by human-emitted greenhouse gasses ends up in the atmosphere.

Similar portions end up getting soaked in by the land and by melting

glaciers. The rest, about

90 percent,

finds its way into the oceans.

The

ocean is thus the best, most reliable global thermometer available.

For good reason, most scientists wait for readings from this big, wet

thermostat to get an idea where global temperatures are headed and

how fast. And what some of the world’s top ocean researchers found

this week was that during 2017 the

top 6,000 feet of the world’s oceans experienced their hottest year

ever recorded.

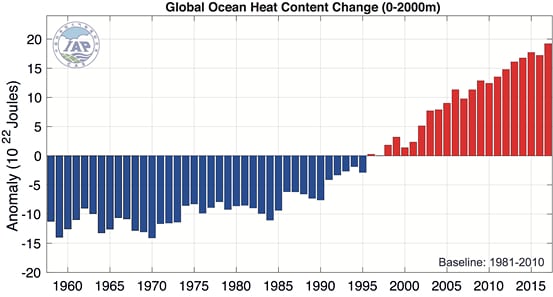

(Ocean

heat content change since 1958. Illustration: Cheng and Zhu

(2018), Advances

in Atmospheric Sciences.)

Not

only was 2017 the hottest ocean year on record, the heat gain from

the previous hottest ocean year (2015) was quite considerable. In

all 15,100,000,000,000,000,000,000

Joules of heat energy were added by the world ocean from 2015 to

2017.

By comparison, 4,184,000,000 Joules were produced by the Hiroshima

bomb. The world ocean is now taking in a similar amount of heat every

3-5 seconds.

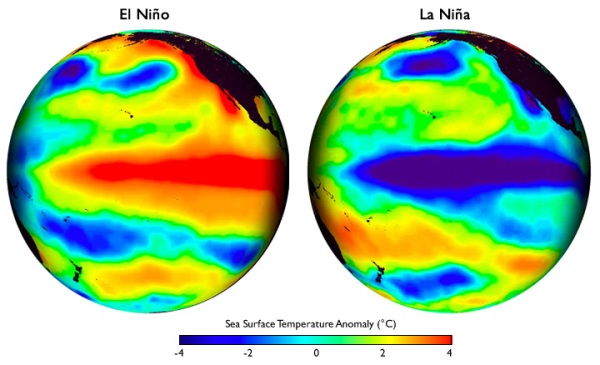

In

the atmosphere, we tend to focus on El Nino years as the hot ones in

an ongoing upward trend.

This is because warm surface waters spreading across the Equatorial

Pacific belch a bit of that huge volume of stored ocean heat back

into the atmosphere. But during La Nina years, cooler surface waters

across wide regions of the Equator swallow up more of the atmospheric

heat. It is during these years that oceans tend to warm the most

swiftly even as atmospheric warming tends to take a break. 2017 saw a

weak La Nina and a comparatively strong rate of related ocean heat

gain. And though atmospheric

temperatures were ‘only’ the second hottest ever recorded

according to NASA,

ocean temperatures tracked further into uncharted territory.

(During

El Nino years [left], the global oceans transfer a portion of their

vast store of warmth to the atmosphere. During La Nina years [right]

the oceans draw in more of the atmosphere’s heat. Image

source: Climate.gov.)

It’s

worth noting that ocean heat gain is presently both quite rapid and

rather steady. All

of the past five years were each one of the five hottest ocean years

ever recorded.

Global temperature gain thus hasn’t slowed. And though atmospheric

temperature gain has accelerated during recent years, the ocean

measure hints that overall heat gain per year has been pretty steady

since the mid 1990s. At least for the top 6,000 feet of the world’s

surface waters (though other measures provide some hints at

acceleration [see image at top of this post]). An observation that

would seem to reinforce the present decadal rate of temperature

increase in the range of 0.15 to 0.20 C every ten years or about 30

to 50 times faster than the warming that ended the last ice age.

To

be clear, the primary driver of what is a very rapid warming in the

geological context is human fossil fuel burning and related carbon

emissions in the range of 11 billion tons per year. Halting fossil

fuel burning is therefore critical to slowing down and ultimately

stopping the present rate of warming and dangerous related

atmospheric and ocean carbon addition.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.