Robert Parry goes into the story of the Magnitsky Act and how the authorities in the West do not want the truth to be known

This is an example of MAJOR censorship in the West. I have looked for this film on-line

It has been truly DISAPPEARED for all intents and purposes.

I did find a version of the film dubbed in Russian (below). Aoart from that you can watch the film by going to the FOLLOWING LINK

A

Blacklisted Film and the New Cold War

Special

Report: As Congress still swoons over the anti-Kremlin Magnitsky

narrative, Western political and media leaders refuse to let their

people view a documentary that debunks the fable, reports Robert

Parry

Robert

Parry

2

August, 2017

Why

is the U.S. mainstream media so frightened of a documentary that

debunks the beloved story of how “lawyer” Sergei Magnitsky

uncovered massive Russian government corruption and died as a result?

If the documentary is as flawed as its critics claim, why won’t

they let it be shown to the American public, then lay out its

supposed errors, and use it as a case study of how such fakery works?

Instead

we – in the land of the free, home of the brave – are protected

from seeing this documentary produced by filmmaker Andrei Nekrasov

who was known as a fierce critic of Russian President Vladimir Putin

but who in this instance found the West’s widely accepted Magnitsky

storyline to be a fraud.

Instead,

last week, Senate Judiciary Committee members sat in rapt attention

as hedge-fund operator William Browder wowed them with a reprise of

his Magnitsky tale and suggested that people who have challenged the

narrative and those who dared air the documentary one time at

Washington’s Newseum last year should be prosecuted for violating

the Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA).

It

appears that Official Washington’s anti-Russia hysteria has reached

such proportions that old-time notions about hearing both sides of a

story or testing out truth in the marketplace of ideas must be cast

aside. The new political/media paradigm is to shield the American

people from information that contradicts the prevailing narratives,

all the better to get them to line up behind Those Who Know Best.

Nekrasov’s

powerful deconstruction of the Magnitsky myth – and the film’s

subsequent blacklisting throughout the “free world” – recall

other instances in which the West’s propaganda lines don’t stand

up to scrutiny, so censorship and ad hominem attacks become the

weapons of choice to defend “perception

management”

narratives in geopolitical hot spots such as Iraq (2002-03), Libya

(2011), Syria (2011 to the present), and Ukraine (2013 to the

present).

But

the Magnitsky myth has a special place as the seminal fabrication of

the dangerous New Cold War between the nuclear-armed West and

nuclear-armed Russia.

In

the United States, Russia-bashing in The New York Times and other

“liberal media” also has merged with the visceral hatred of

President Trump, causing all normal journalistic standards to be

jettisoned.

A

Call for Prosecutions

Browder,

the American-born co-founder of Hermitage Capital Management who is

now a British citizen, raised the stakes even more when

he testified that

the people involved in arranging a one-time showing of Nekrasov’s

documentary, “The Magnitsky Act: Behind the Scenes,” at the

Newseum should be held accountable under FARA, which has penalties

ranging up to five years in prison.

Browder

testified: “As part of [Russian lawyer Natalie] Veselnitskaya’s

lobbying, a former Wall Street Journal reporter, Chris Cooper of the

Potomac Group, was hired to organize the Washington, D.C.-based

premiere of a fake documentary about Sergei Magnitsky and myself.

This was one the best examples of Putin’s propaganda.

“They

hired Howard Schweitzer of Cozzen O’Connor Public Strategies and

former Congressman Ronald Dellums to lobby members of Congress on

Capitol Hill to repeal the Magnitsky Act and to remove Sergei’s

name from the Global Magnitsky bill. On June 13, 2016, they funded a

major event at the Newseum to show their fake documentary, inviting

representatives of Congress and the State Department to attend.

“While

they were conducting these operations in Washington, D.C., at no time

did they indicate that they were acting on behalf of Russian

government interests, nor did they file disclosures under the Foreign

Agent Registration Act. United States law is very explicit that those

acting on behalf of foreign governments and their interests must

register under FARA so that there is transparency about their

interests and their motives.

“Since

none of these people registered, my firm wrote to the Department of

Justice in July 2016 and presented the facts. I hope that my story

will help you understand the methods of Russian operatives in

Washington and how they use U.S. enablers to achieve major foreign

policy goals without disclosing those interests.”

Browder’s

Version

While

he loosely accused a number of Americans of felonies, Browder

continued to claim that Magnitsky was a crusading “lawyer” who

uncovered a $230 million tax-fraud scheme carried out ostensibly by

Browder’s companies but, which, according to Browder’s account,

was really engineered by corrupt Russian police officers who then

arrested Magnitsky and later were responsible for his death in a

Russian jail.

Browder’s

narrative has received a credulous hearing by Western politicians and

media already inclined to think the worst of Putin’s Russia and

willing to treat Browder’s claims as true without serious

examination. However, beyond the self-serving nature of Browder’s

tale, there are many holes in the story, including whether Magnitsky

was really a principled lawyer or instead a complicit accountant.

According

to Browder’s own biographical

description of

Magnitsky, he received his education at the Plekhanov Institute in

Moscow, a reference to Plekhanov Russian University of Economics, a

school for finance and business, not a law school.

Nevertheless,

the West’s mainstream media – relying on the word of Browder –

has accepted Magnitsky’s standing as a “lawyer,” which

apparently fits better in the narrative of Magnitsky as a crusading

corruption fighter rather than a potential co-conspirator with

Browder in a complex fraud, as the Russian government has alleged.

Magnitsky’s

mother also has described her son as an accountant, although telling

Nekrasov in the documentary “he wasn’t just an accountant; he was

interested in lots of things.” In the film, the “lawyer” claim

is also disputed by a female co-worker who knew Magnitsky well. “He

wasn’t a lawyer,” she said.

In

other words, on this high-profile claim repeated by Browder again and

again, it appears that presenting Magnitsky as a “lawyer” is a

convenient falsehood that buttresses the Magnitsky myth, which

Browder constructed after Magnitsky’s death from heart failure

while in pre-trial detention.

But

the Magnitsky myth took off in 2012 when Browder sold his tale to

neocon Senators Ben Cardin, D-Maryland, and John McCain, R-Arizona,

who threw their political weight behind a bipartisan drive in

Congress leading to the passage of the Magnitsky sanctions act, the

opening shot in the New Cold War.

A

Planned Docudrama

Browder’s

dramatic story also attracted the attention of Russian filmmaker

Andrei Nekrasov, a well-known critic of Putin from previous films.

Nekrasov set out to produce a docudrama that would share Browder’s

good-vs.-evil narrative to a wider public.

Nekrasov

devotes the first half hour of the film to allowing Browder to give

his Magnitsky account illustrated by scenes from Nekrasov’s planned

docudrama. In other words, the viewer gets to see a highly

sympathetic portrayal of Browder and Magnitsky as supposedly corrupt

Russian authorities bring charges of tax fraud against them.

However,

Nekrasov’s documentary

project takes an unexpected turn when

his research turns up numerous contradictions to Browder’s

storyline, which begins to look more and more like a corporate cover

story. For instance, Magnitsky’s mother blames the negligence of

prison doctors for her son’s death rather than a beating by prison

guards as Browder had pitched to Western audiences.

Nekrasov

also discovered that a woman who had worked in Browder’s company

blew the whistle before Magnitsky talked to police and that

Magnitsky’s original interview with authorities was as a suspect,

not a whistleblower. Also contradicting Browder’s claims, Nekrasov

notes that Magnitsky doesn’t even mention the names of the police

officers in a key statement to authorities.

When

one of the Browder-accused police officers, Pavel Karpov, filed a

libel suit against Browder in London, the case was dismissed on

technical grounds because Karpov had no reputation in Great Britain

to slander. But the judge seemed sympathetic to the substance of

Karpov’s complaint.

Browder

claimed vindication before adding an ironic protest given his

successful campaign to prevent Americans and Europeans from seeing

Nekrasov’s documentary

.

“These

people tried to shut us up; they tried to stifle our freedom of

expression,” Browder complained. “[Karpov] had the audacity to

come here and sue us, paying high-priced libel lawyers to come and

terrorize us in the U.K.”

The

‘Kremlin Stooge’ Slur

A

pro-Browder account published

at the Daily Beast on July 25 – attacking Nekrasov and his

documentary – is entitled “How an Anti-Putin Filmmaker Became a

Kremlin Stooge,” a common slur used in the West to discredit and

silence anyone who dares question today’s Russia-hating groupthink.

Russian

police officer Pavel Karpov (right) meets the actor who portrays him

in the docudrama portions of “The Magnitsky Act: Behind the

Scenes.”

The

article by Katie Zavadski accuses Nekrasov of being in the tank for

the Kremlin and declares that “The movie is so flattering to the

Russian narrative that Pavel Karpov — one of the police officers

accused of being responsible for Magnitsky’s death — plays

himself.”

But

that’s not true. In fact, there is a scene in the documentary in

which Nekrasov invites the actor who plays Karpov in the docudrama

segment to sit in on an interview with the real Karpov. There’s

even a clumsy moment when the actor and police officer bump into a

microphone as they shake hands, but Zavadski’s falsehood would not

be apparent unless you had somehow gotten access to the documentary,

which has been effectively banned in the West.

In

the documentary, Karpov, the police officer, accuses Browder of lying

about him and specifically contests the claim that he (Karpov) used

his supposedly ill-gotten gains to buy an expensive apartment in

Moscow. Karpov came to the interview with documents showing that the

flat was pre-paid in 2004-05, well before the alleged hijacking of

Browder’s firms.

Karpov

added wistfully that he had to sell the apartment to pay for his

failed legal challenge in London, which he said he undertook in an

effort to clear his name. “Honor costs a lot sometimes,” the

police officer said.

Karpov

also explained that the investigations of Browder’s tax fraud

started well before the Magnitsky controversy, with an examination of

a Browder company in 2004.

“Once

we opened the investigation, a campaign in defense of an investor

started,” Karpov said. “Having made billions here, Browder forgot

to tell how he did it. So it suits him to pose as a victim. …

Browder and company are lying blatantly and constantly.”

However,

since virtually no one in the West has seen this interview, you can’t

make your own judgment as to whether Karpov is credible or not.

A

Painful Recognition

Yet,

in reviewing the case documents and noting Browder’s inaccurate

claims about the chronology, Nekrasov finds his own doubts growing.

He discovers that European officials simply accepted Browder’s

translations of Russian documents, rather than checking them

independently. A similar lack of skepticism prevailed in the United

States.

In

other words, a kind of trans-Atlantic groupthink took hold with clear

political benefits for those who went along and almost no one willing

to risk the accusation of being a “Kremlin stooge” by showing

doubt.

As

the documentary proceeds, Browder starts avoiding Nekrasov and his

more pointed questions. Finally, Nekrasov hesitantly confronts the

hedge-fund executive at a party for Browder’s book, Red

Notice,

about the Magnitsky case.

The

easygoing Browder of the early part of the documentary — as he lays

out his seamless narrative without challenge — is gone; instead, a

defensive and angry Browder appears.

“It’s

bullshit,” Browder says when told that his presentations of the

documents are false.

But

Nekrasov continues to find more contradictions and discrepancies. He

discovers evidence that Browder’s web site eliminated an earlier

chronology that showed that in April 2008, a 70-year-old woman named

Rimma Starova, who had served as a figurehead executive for Browder’s

companies, reported the theft of state funds.

Nekrasov

then shows how Browder’s narrative was changed to introduce

Magnitsky as the whistleblower months later, although he was then

described as an “analyst,” not yet a “lawyer.”

As

Browder’s story continues to unravel, the evidence suggests that

Magnitsky was an accountant implicated in manipulating the books, not

a crusading lawyer risking everything for the truth.

A

Heated Confrontation

In

the documentary, Nekrasov struggles with what to do next, given

Browder’s financial and political clout. Finally securing another

interview, Nekrasov confronts Browder with the core contradictions of

his story. Incensed, the hedge-fund executive rises up and threatens

the filmmaker.

Financier

William Browder (right) with Magnitsky’s widow and son, along with

European parliamentarians.

“I’d

be very careful going out and trying to do a whole sort of thing

about Sergei [Magnitsky] not being the whistleblower, it won’t do

well for your credibility on this show,” Browder said. “This is

sort of the subtle FSB version,” suggesting that Nekrasov was just

fronting for the Russian intelligence service.

In

the pro-Browder account published

at the Daily Beast on July 25, Browder described how he put down

Nekrasov by telling him, “it sounds like you’re part of the FSB.

… Those are FSB questions.”

But

that phrasing is not what he actually says in the documentary,

raising further questions about whether the Daily Beast reporter

actually watched the film or simply accepted Browder’s account of

it. (I posed that question to the Daily Beast’s Katie Zavadski

by email, but have not gotten a reply.)

The

documentary also includes devastating scenes from depositions of a

sullen and uncooperative Browder and a U.S. government investigator,

who acknowledges relying on Browder’s narrative and documents in a

related case against Russian businesses.

In

an April 15, 2015 deposition of Browder, he, in turn, describes

relying on reports from journalists to “connect the dots,”

including the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project

(OCCRP), which is funded by the U.S. government and financial

speculator George Soros. Browder said the reporters “worked with

our team.”

While

taking money from the U.S. Agency for International Development and

Soros, the OCCRP also targeted Ukraine’s elected President Viktor

Yanukovych with accusations of corruption prior to the Feb. 22, 2014

coup that ousted Yanukovych, an overthrow that was supported by the

U.S. State Department and escalated the New Cold War with Russia.

OCCRP

played a key role, too, in the so-called Panama Papers, purloined

documents from a Panamanian law firm that were used to develop attack

lines against Russian President Vladimir Putin although his name

never appeared in the documents.

After

examining the money-movement charts published by OCCRP about the

Magnitsky case, Nekrasov notes that the figures don’t add up and

wonders how journalists could “peddle these wooly maths.” He also

observed that OCCRP’s Panama Papers linkage of Magnitsky’s $230

million fraud and payments to an ally of Putin made no sense because

the dates of the Panama Papers transactions preceded the dates of the

alleged Magnitsky fraud.

The

Power of Myth

Nekrasov

suggests that the power of Browder’s convoluted story rested, in

part, on a Hollywood perception of Moscow as a place where evil

Russians lurk around every corner and any allegation against

“corrupt” officials is believed. The Magnitsky tale “was like a

film script about Russia written for the Western audience,”

Nekrasov says.

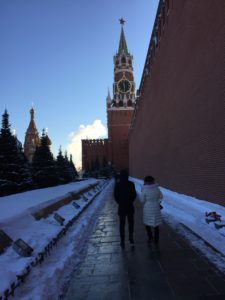

Red

Square in Moscow with a winter festival to the left and the Kremlin

to the right. (Photo by Robert Parry)

But

the Browder’s narrative also served a strong geopolitical interest

to demonize Russia at the dawn of the New Cold War.

In

the documentary’s conclusion, Nekrasov sums up what he had

discovered: “A murdered hero as an alibi for living suspects.” He

then ponders the danger to democracy: “So do we allow graft and

greed to hide behind a political sermon? Will democracy survive if

human rights — its moral high ground — is used to protect selfish

interests?”

But

Americans and Europeans are being spared the discomfort of having to

answer that question or to question their representatives about the

failure to skeptically examine this case that has pushed the planet

on a course toward a possible nuclear war.

Instead,

the mainstream Western media has hurled insults at Nekrasov even as

his documentary is blocked from any significant public viewing.

Despite

Browder’s professed concern about the London libel case that he

claimed was an attempt “to stifle our freedom of expression,” he

has sicced his lawyers on anyone who might be thinking about showing

Nekrasov’s documentary to the public.

The

documentary was set for a premiere at the European Parliament in

Brussels in April 2016, but at the last moment – faced with

Browder’s legal threats – the parliamentarians pulled the plug.

Nekrasov encountered similar resistance in the United States. There

were hopes to show the documentary to members of Congress but the

offer was rebuffed. Instead a room was rented at the Newseum near

Capitol Hill.

Browder’s

lawyers then tried to strong arm the Newseum, but its officials

responded that they were only renting out a room and that they had

allowed other controversial presentations in the past.

“We’re

not going to allow them not to show the film,” said Scott Williams,

the Newseum’s chief operating officer. “We often have people

renting for events that other people would love not to have happen.”

In

an article about the controversy in June 2016, The New York

Times added that

“A screening at the Newseum is especially controversial because it

could attract lawmakers or their aides.”

One-Time

Showing

So,

Nekrasov’s documentary got a one-time showing with a follow-up

discussion moderated by journalist Seymour Hersh. However, except for

that audience, the public of the United States and Europe has been

essentially shielded from the documentary’s discoveries, all the

better for the Magnitsky myth to retain its power as a seminal

propaganda moment of the New Cold War.

After

the Newseum presentation, a

Washington Post editorial branded

Nekrasov’s documentary Russian “agit-prop” and sought to

discredit Nekrasov without addressing his many documented examples of

Browder’s misrepresenting both big and small facts in the case.

Instead,

the Post accused Nekrasov of using “facts highly selectively” and

insinuated that he was merely a pawn in the Kremlin’s “campaign

to discredit Mr. Browder and the Magnitsky Act.”

Like

the recent Daily Beast story, which falsely claimed that Nekrasov let

the Russian police officer Karpov play himself, the Post

misrepresented the structure of the film by noting that it mixed

fictional scenes with real-life interviews and action, a point that

was technically true but willfully misleading because the fictional

scenes were from Nekrasov’s original idea for a docudrama that he

shows as part of explaining his evolution from a believer in

Browder’s self-exculpatory story to a skeptic.

But

the Post’s deception – like the Daily Beast’s falsehood – is

something that almost no American would realize because almost no one

has gotten to see the ilm.

The

Post’s editorial gloated: “The film won’t grab a wide audience,

but it offers yet another example of the Kremlin’s increasingly

sophisticated efforts to spread its illiberal values and mind-set

abroad. In the European Parliament and on French and German

television networks, showings were put off recently after questions

were raised about the accuracy of the film, including by Magnitsky’s

family.

“We

don’t worry that Mr. Nekrasov’s film was screened here, in

an open society. But it is important that such slick spin be fully

exposed for its twisted story and sly deceptions.”

The

Post’s arrogant editorial had the feel of something you might

read in a totalitarian society where

the public only hears about dissent when the Official Organs of the

State denounce some almost unknown person for saying something that

almost no one heard.

It

is also unlikely that Americans and Europeans will get a chance to

view this blacklisted documentary in the future. In an email

exchange, the film’s Norwegian producer Torstein Grude told me that

“We have been unsuccessful in releasing the film to TV so far.

ZDF/Arte [a major European network] pulled it from transmission a few

days before it was supposed to be aired and the other broadcasters

seem scared as a result. Netflix has declined to take it. …

“The

film has no other release at the moment. Distributors are scared by

Browder’s legal threats. All involved financiers, distributors,

producers received thick stacks of legal documents (300+ pages)

threatening lawsuits should the film be released.” [Grude sent me a

special password so I could view the documentary on Vimeo.]

The

blackout continues even though the Magnitsky issue and Nekrasov’s

documentary have become elements in the recent controversy over a

meeting between a Russian lawyer and Donald Trump Jr. [See

Consortiumnews.com’s “How

Russia-gate Met the Magnitsky Myth.”]

So

much for the West’s vaunted belief in freedom of expression and the

democratic goal of encouraging freewheeling debates about issues of

great public importance. And, so much for the Post’s empty rhetoric

about our “open society.”

Investigative

reporter Robert Parry broke many of the Iran-Contra stories for The

Associated Press and Newsweek in the 1980s. You can buy his latest

book, America’s

Stolen Narrative, either

in print

here or

as an e-book (from Amazon andbarnesandnoble.com).

Russian Film Director censored by EU: Western media are misrepresenting Magnitsky - Browder case

Here is a version of the documentary dubbed in Russian

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.