Half a World Away From Harvey, Global Warming Fueled Deluges Now Impact 42 Million People

Rising sea surface temperatures in South Asia led to more moisture in the atmosphere, providing this year’s monsoon with its ammunition for torrential rainfall. — The Pacific Standard

While flooding is common in the region, climate change has spurred dramatic weather patterns, greatly exacerbating the damage. As sea temperatures warm, moisture increases, a dynamic also at play in the record-setting rainfall in Texas. — Think Progress

******

30 August, 2017

With Harvey delivering its own hammer blow of worst-ever-seen rainfall to Texas, 42 million people are now impacted by record flooding half a world away. The one thing that links these two disparate disasters? Climate Change.

A Worsening Flood Disaster in South Asia

As Harvey was setting its sights on the Texas Coast this time last week, another major rainfall disaster was already ongoing. Thousands of miles away, South Asia was experiencing historic flooding that seven days ago had impacted 24 million people.

At the time, two tropical weather systems were developing over a very warm Pacific. They were angling in toward a considerably pumped up monsoonal moisture flow. And they appeared bound and determined to unleash yet more misery on an already suffering region.

As of Monday, the remnants of tropical cyclone Hato had entered the monsoonal flow and was unleashing its heavy rains upon Nepal. The most recent in a long chain of systems that just keeps looping more storms in over the region to disgorge they water loads on submerged lands.

By Wednesday, the number of people suffering from flooding in India, Bangladesh and Nepal had jumped by 18 million in just one week to more than 42 million. With 32 million impacted in India, 8.6 million in Bangladesh, and 1.7 million in Nepal. More tragically, 1,200 people have perished due to both landslides and floods as thousands of square miles have been submerged and whole regions have been crippled with roads, bridges, and airports washing out. Adding to this harsh toll are an estimated 3.5 million homes that have been damaged or destroyed in Bangladesh alone.

Worst impacts are likely to focus on Bangladesh which is down-stream of flooded regions in Nepal and India. As of last week, 1/3 of this low-lying country had been submerged by rising water. With intense rains persisting during recent days, this coverage is likely to have expanded.

Hundreds of thousands of people have now funneled into the country’s growing disaster shelters. A massive international aid effort is underway as food and water supplies are cut off and fears of disease are growing. The international Red Cross and Red Crescent and other relief agencies have deployed over 2,000 medical teams to the region. Meanwhile, calls for increased assistance are growing.

Warmer Oceans Fuel Tropical Climate Extremes

As with Harvey, this year’s South Asia floods have been fueled by much warmer than normal ocean surface temperatures. These warmer than normal ocean surfaces are evaporating copious amounts of moisture into the tropical atmosphere. This moisture, in turn, is intensifying the monsoonal rains.

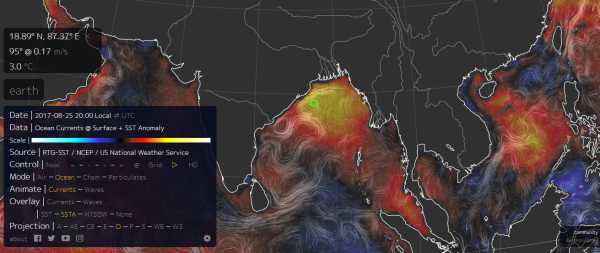

(Very warm ocean surface temperatures related to global warming are contributing to catastrophic South Asian flooding in which 42 million people are now impacted. Image source: Earth Nullschool.)

In the Bay of Bengal, ocean surfaces have recently hit about 3 C above the three decade average. But ocean waters have been warming now for more than a Century following the initiation of widespread fossil fuel burning. So even the present baseline is above 20th Century temperature norms. At this point, such high levels of ocean heat are clearly having an impact on tropical weather.

In an interview with CNN, Reaz Ahmed, the director-general of Bangladesh’s Department of Disaster Management noted last week that:

“This is not normal. Floods this year were bigger and more intense than the previous years.”

Further exacerbating the situation is that fact that glaciers are melting and temperatures are rising in the Himalayas. This increases water flow into rivers during monsoon season even as glacial melt flow into rivers is reduced during the dry season. It’s kind of a flood-drought whammy in which the dry season is growing hotter and drier for places like India, but the wet season is conversely getting pushed toward worsening flood extremes.

Links:

Hat tip to Colorado Bob

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.