IN

LAW, IF MAY CAN’T PASS #QUEENSSPEECH, #CORBYN AUTOMATICALLY BECOMES

PM

12

June, 2017

The

Tories announced today that Theresa May’s ‘Queen’s Speech’

programme for government has been postponed from its expected date of

19 June – clearly because they have so far been unable to reach

agreement with the Democratic Unionists (DUP), who are queasy about

the prospect of going into an unpopular government against the clear

wish of many British people.

Even

the possibility of a Tory-DUP deal has raised tensions and fears in

Northern Ireland, with experts asserting that the collaboration

between the two parties puts

the ‘Good Friday Agreement’ at serious risk,

threatening the fragile peace process.

In

spite of this, the Tories persist in pursuing such a deal for their

own narrow gain,

They

have attempted to justify this tactic by claiming it’s ‘for the

good of the country’ and that Britain would be destabilised,

with no

clear path of transition to a Labour government when

the parliamentary arithmetic means Labour could not achieve –

without the very unlikely and problematic support of the DUP – a

Commons majority.

This

is a lie.

In

the run-up to the 2015 election, which all the pollsters and pundits

incorrectly expected to result in a ‘hung Parliament’, an expert

in constitutional law looked

at the legal precedent and convention surrounding the possibility

that then-incumbent PM David Cameron would fail to get his Queen’s

Speech through a Commons vote.

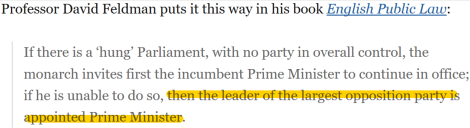

And

he not only concluded that the leader of the next-largest party

would automatically become

Prime Minister, but pointed out no fewer than four occasions

within the last century when exactly that happened.

In

a 2015 article on

the law site Head

of Legal,

Carl Gardiner looked in detail at constitutional law, how it applied

in those four examples and how it would apply to a hung Parliament in

2015. For the detailed legal analysis, read the full article – but

his examples and key conclusions are:

1924:

then-leader Ramsay MacDonald was immediately invited by the king to

form a minority Labour government when the Tories – the largest

single party – could not pass its King’s Speech. MacDonald

did not have

to seek a coalition or demonstrate a functional majority

1929:

MacDonald was again invited

to be PM, even though Labour had won only 287 of the then-615

parliamentary seats, after Tory PM Baldwin resigned upon being unable

to command a Commons majority. Again, MacDonald did not have to

demonstrate a functioning majority

1974:

Harold Wilson was invited by the queen to form a government after

Edward Heath’s attempts to agree a coalition with the Liberals

failed. He immediately formed a minority government in spite of

stating firmly that he would not seek nor enter any coalition

2010:

Then-PM Gordon Brown resigned immediately it became clear that he

could not command a Commons majority, even though David Cameron had

not yet agreed a coalition with the LibDems’ Nick Clegg. The

coalition gave Cameron a functioning majority – but before

the deal with the LibDems was finalised,

he was summoned to the Palace ‘as a matter of course’.

He

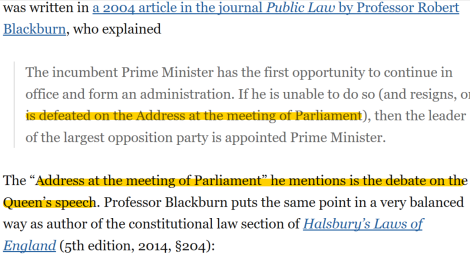

concludes his discussion of the course of events:

and

then goes on to make clear that the crucial test for whether there is

a ‘hung Parliament with no party in overall control is the ability

to pass a Queen’s Speech:

No

wonder that Theresa May has postponed the Queen’s Speech and is

desperately trying – in spite of the clear risk to the safety

of the people of Northern Ireland – to secure the backing of a

demanding DUP that sees no need to compromise on its demands.

If

she cannot get her Queen’s Speech through Parliament at the first

attempt – constitutional law makes Jeremy Corbyn the Prime Minister

by default, without the need for him to do the same.

Jeremy

Corbyn could be forming his own government within weeks – and

without another election

The

only stable and certain thing we have to look forward to is that the

instability and uncertainty we are now experiencing will be permanent

12

June, 2017

Imagine

there was a turkey farm where they were not just being asked to vote

for Christmas, but where the turkeys had organised themselves into

various groups and each group had different ideas about who’d do

better out of Christmas than the other lot; and where they could

actually try to move the date of Christmas; and where the rules about

voting for or against Christmas were almost impossible to understand

in any case.

That’s

more or less where the UK is now: a dysfunctional version of the

Bernard Matthews estate – stuffed.

The

question “When will the next election be?” ought to be easy to

answer. It is not. The answer should be “not before 5 May 2022”.

Beyond that – in terms of the formal legal position – it is

extremely difficult to be, in the buzzword of the moment, “certain”.

It is likely to be before 5 May 2022.

In

the old days an election could be called pretty much when the prime

minister wanted to or, more rarely, a government lost a vote of

confidence. That’s how we got Margaret Thatcher, for example. When

the Labour government led by James Callaghan lost a vote of

confidence on 28 March 1979, that was that. The election was on.

Now,

partly because of some systematic abuse of the power by prime

ministers engineering pre-election booms, we have the Fixed-term

Parliaments Act. This was passed in 2011 by the Coalition Government

at the insistence of the Liberal Democrats, and was supposed to

weaken prime ministerial privileges by transferring the power to call

an election to the House of Commons as a whole. Under this law, an

early election (before 5 May 2022) can only be held if one (not both)

of these conditions is met:

General

election 2017: Irish PM warns May about deal with the DUP

A)

If a motion for an early general election is agreed either by at

least two-thirds of the whole House (including vacant seats), ie 434

Members out of 650, or without division (ie so unanimous is the House

that it can show its opinion with a deafening chorus of “yes” to

the Speaker, so that a formal vote would be unnecessary, a nod to old

fashioned conventions).

Or,

B) If a motion of no confidence is passed and no alternative

government is confirmed by the Commons within 14 days by means of a

confidence motion.

When

Theresa May made her dramatic announcement in the street outside

Number 10 on 18 April, it was technically not legally binding,

despite the sensation it caused, because it didn’t follow the 2011

Act’s procedures. That was, if you recall, why there was all that

talk about whether Jeremy Corbyn would agree to it – because only

with Labour votes could the Commons have the two-thirds majority

required by law. (It would have been possible for her to propose no

confidence in her own government, but that would have been too

bizarre for her). Had Corbyn said no to an early election then May

wouldn’t have had her bid for a new mandate (if only she’d known

what was to follow).

But

Corbyn had to agree to an election as the political damage of running

away from one, and being seen as cowardly, would be too great.

(Shrewdly, the SNP opted to abstain.) Ironically, some commented at

that time that Corbyn should have refused to facilitate the 2017

election because it would have smashed the Labour Party for ever and

made May invincible. That recent episode also persuaded some that the

Fixed-term Parliaments Act was irrelevant; maybe that’s true under

a majority government – but it comes into its own viciously when

there’s a minority administration, as we are about to discover.

So

now what would need to happen to trigger an early election?

The

immediate option is for the Prime Minister to pull the rug on her own

“certain” pact with the DUP at a time of her choosing –

provided all of her MPs and all 10 DUP MPs vote solidly in a vote of

no confidence in their own government (more irony, right there).

Bizarre, but possible.

That

would just be the first step, though. There would then be a period of

two weeks in which Corbyn could seek to form a government of his own.

Say

he managed to pull off a similar pact to May’s, but instead with

the Liberal Democrats, the Green MP Caroline Lucas, the Scottish

Nationalists and Plaid Cymru. There is also the possibility, merely

theoretical of course, that the DUP could switch sides (but as they

despise Corbyn’s past links to Sinn Fein, in this particular

instance they almost certainly won’t). Corbyn would even then not

command a full majority, and the Conservatives might want to bring

him down straight away with the vote of no confidence required within

14 days.

The

other crucial factor in such a vote of confidence is how many MPs

would abstain from voting. Corbyn would still need some votes from

other parties to bridge the 60-seat gap between himself and the

Tories (that is if the Tories did intend to vote against him). A

Corbyn government’s survival relies on the DUP abstaining, which it

probably would not – but they could threaten it now, to maximise

leverage over the Tories. That, in turn, might be unacceptable to the

other parties and the mainland British voters.

The

point here is that votes of no confidence have only to be a simple

majority of the votes cast. Corbyn would only need 50 per cent plus

one of the votes, not a fixed barrier of 50 per cent plus one of the

number of MPs (unlike the two-thirds rule for an early dissolution).

Even so, he’d definitely need minority support if the Conservatives

were against him.

Even

if such events occurred, he might only be Prime Minister for a short

time – the 2011 Act isn’t clear on whether May would resign

straight away. Still, the logic is that Corbyn would need to face the

Commons as Prime Minister in order to debate the motion of confidence

in Her Majesty’s government – because that would have to be the

current government and could only be the one led by Corbyn, seeing as

they'd already passed the motion about May. If he lost, he would be

prime minister during the election campaign, because the Queen’s

government must continue and there cannot be a vacancy. He would have

to stop himself attacking the record “of this government”,

because it is technically his own. The irony.

Jeremy

Corbyn says there may be another election later this year

Another

scenario is that the DUP become disillusioned with May and opt out

early, and then vote against her government in a vote of no

confidence with every other opposition MP. That would bring her down,

and usher in a Corbyn-led government, at least for the short period

before it too faces a vote of no confidence (and assuming it loses,

which it might not), within a fortnight. Again it probably rests on

the DUP abstaining, which makes them kingmakers once again.

So,

either way, after May lost her vote, Corbyn could conceivably form a

completely go-it-alone minority administration and put forward

measures that were timid enough to pass without a vote of no

confidence being tabled, or he could brazen it out. This is what he

and McDonnell are floating. In such a situation the power of the

smaller parties becomes hugely magnified.

Given

all that, the Labour and Conservative parties could decide to

conspire, as last April, to pass a motion calling for an early poll,

just to end the chaos. They’d have to agree to forget the tussle

about who gets to be prime minister going into the election and not

bother with a series of votes of confidence. Unless they compromised

on Tim Farron being “acting” prime minister for a fortnight; this

is how odd it gets.

The

difficult thing is that, if it is in the party political interest of

one major party go for an election – because they have a commanding

poll lead – then it is not necessarily in the interests of the

other party, who would want to avoid it like hell (though Corbyn was

game enough to go for it a few weeks ago). So the two-thirds rule

couldn’t work.

Nor,

in the alternate case of a motion of no confidence, is it necessarily

something the Lib Dems or, say, the SNP would welcome if they felt

they would lose more ground by having an early poll. For the SNP, it

might mean falling below half the Scottish seats in the Commons – a

psychological barrier they clearly fear.

So

all the way through the Brexit talks we could be left with permanent

chaos.

That,

in a way, was the point and the design of the Fixed-term Parliaments

Act. It was aimed at cementing the Lib Dems and the Conservatives in

a tight coalition government for a full five-year programme, and to

minimise the risk that one or other of them would peel off (or an

internal faction pull the administration down). The whole idea was to

make an early election so difficult to achieve it just wouldn’t

happen. You might think that the Fixed-term Parliaments Act was a

mistake and a thing “of its time”, and the best thing would be to

abolish it: but that would require a majority in the Commons, so

could amount to much the same thing.

Yes,

the Tories and the DUP could ask Parliament to abolish the Act now,

but that would also mean breaching Section 7 of the Act, which

requires the prime minister to make arrangements between June and

November 2020 for a committee to carry out a review of the operation

of the Act. Not binding on the following parliament, that, but

something of a brake on a hasty abolition of the Act. The House of

Lords (who didn’t like it much in the first place) would also need

to be agree, though it is surely primarily a Commons matter.

Abolition

of the 2011 Act was in the Conservative manifesto this time round,

but the DUP was silent on this issue. Whether it is subject to the

Salisbury Convention that states a “winning” party manifesto

cannot be blocked is debatable. No doubt someone would try and send

it off to judicial review, ironically including to the European

Court. You could argue, for example, that the effect of abolition at

that moment would be to extend the life of a parliament, contrary to

the Parliament Act (the 1911 not the 2011 one). It could get messy.

The

other thing to remember is that, under the 2011 Act and previous

conventions, a government can lose all manner of important votes –

on the Budget, say, or Trident, or Brexit, or the Queen’s Speech –

but still not be thrown out if it returns to the Commons and then

wins a vote of no confidence (which, by the way, only counts if it is

couched in the special wording in the 2011 Act – “That this House

has no confidence in Her Majesty’s Government”. If this motion is

carried, there is a 14 calendar day period in which to form a new

Government, confirmed in office by a resolution as follows: “That

this House has confidence in Her Majesty’s Government”. So if the

Commons just wanted to blow off steam in a big protest they could

pass a motion saying, for example, “That this House has no

confidence in the policies of Her Majesty’s Government” or “This

House has no confidence in the Prime Minister”, and nothing

electoral need happen). In the 1990s, John Major’s government lost

loads of votes but he just kept going for a full five year term; it

wasn’t much fun for anyone

All

of that is just the constitutional rules. Then there’s the

politics.

We

now have an unworkable situation where the Conservatives’ unspoken

but settled public policy is that May will not lead their party into

the next general election, whenever it occurs. Therefore they need to

organise a leadership election (or the coronation of a successor) in

advance of that. Given that the party polls its MPs in exhaustive

ballots and then reaches out to the membership across the country

over months, that is not a rapid process. In the meantime, the

opposition parties are in effect given notice that an election is

coming (McDonnell even claims that Labour knew there’d be an

election early precisely because May ruled it out last November). In

such circumstances party calculation and game-playing become

amplified, and not necessarily will they deliver strong and stable

administration.

To

get a new Tory leader without a bloody battle requires an old one to

quit, preferably quietly. Would May oblige? Would she insist on being

a candidate once again (as Corbyn did in similar circumstances)? It’s

likely she’d not resist, but then again she has a reputation for

being “bloody difficult”.

It

is a complete shambles and will be for the foreseeable future. It

might also drag the Queen into controversy if we find, for example,

that the only way of breaking the deadlock would be to revive the

Royal Prerogative, explicitly ended in the 2011 Act. Or if she

invited Corbyn to form a government when it was plain he’d lose a

subsequent vote of no confidence, because the wording of the Act is

imperfect. Her courts might have to decide on Her decisions about Her

government. That really would be a crisis. In any event, it would not

be strong and stable governance of Her realm.

The

only stable and certain thing we have to look forward to is that the

instability and uncertainty will be permanent. The most terrifying

thing is if there was another election and it gave us another hung

parliament. This is quite possible, given that there are relatively

few swing seats to fight over these days, a modern psephological

accident.

The

big factors that have moved elections in recent years – the

collapse of the Lib Dems in 2015 (which gave David Cameron his

majority); the rise and fall of the SNP which helped Cameron and then

Corbyn in 2015 and 2017; and the rise in youth participation, which

boosted Corbyn – must surely be subject to the law of diminishing

returns. A boundary review might tilt things towards the

Conservatives, but not for a while (until 2020 at the earliest). So

the next election is likely to be tight and, if held in the next year

or two, not so very different to the last one. It’s also one which,

given the economic crash that is on its way, especially with Brexit,

no politician in their right mind should actually want to win: why

not let the other lot get the blame? But the Fixed-term Parliaments

Act doesn’t say anything about that, either.

The

conclusion? If countries get the politicians they deserve, you wonder

what the British people have done to have this kind of karma visited

upon them.

Labour

deputy leader Tom Watson has asked Prime Minister Theresa May whether

media mogul Rupert Murdoch had anything to do with the appointment of

Brexit-backstabber Michael Gove in Sunday’s post-election cabinet

reshuffle.

Gove

returned to the front benches as environment secretary, despite

having a very public falling out with May less than a year ago.

Pundits suggest it is a clear sign of just how precarious the PM’s

position has become.

The

influential Leave campaigner was publicly humiliated during last

year’s Conservative leadership race, when he was eliminated in the

second round, falling behind May and the newly minted Leader of the

House, Andrea Leadsom.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.