Rates of Hothouse Gas Accumulation Continue to Spike as the Amazon Rainforest Bleeds Carbon

18

November, 2016

Back

in June, atmospheric

carbon monitors indicated that the Amazon Rainforest was leeching out

more carbon dioxide than it was taking in.

This is kind of a big deal — because the vast expanse of trees and

vegetation in the Amazon represents a gift nature has given to us.

For all that lush vegetation draws in a considerable amount of carbon

dioxide and stores it in leaves, wood, bark and soil. And this

draw-down, in its turn, considerably reduces the overall rate of

atmospheric carbon accumulation coming from human fossil fuel

burning.

Over

the years and decades, this great service has saved the world from an

even more rapid warming than

it is presently experiencing.

But not even the great forests could stand for long against the

unprecedented plume of carbon coming from human fossil fuel industry.

For the great belching of heat-trapping gas by all the world’s

engines, furnaces, and fires is equal to about 4

or 5 of the Siberian flood basalts that

triggered the worst hothouse extinction event in Earth’s deep

history.

And

so the world has warmed very rapidly regardless of the mighty effort

on the part of forests like the Amazon. And that very heat is now

harming the trees and damaging the earth to which they are wed. For

when soils warm, the carbon they take in is leached out. And along

with the heat comes fires that can, in a matter of minutes, reduce

trees to ash and return the captured heat-trapping carbon to the

world’s airs.

Atmospheric

CO2 Accumulation Increasing Despite Plateau in Human Carbon Emissions

Now

such a destructive process appears to be well under way. And it seems

that an apparent blow-back of greenhouse gasses from one of the

world’s largest carbon sinks is presently ongoing even as rates of

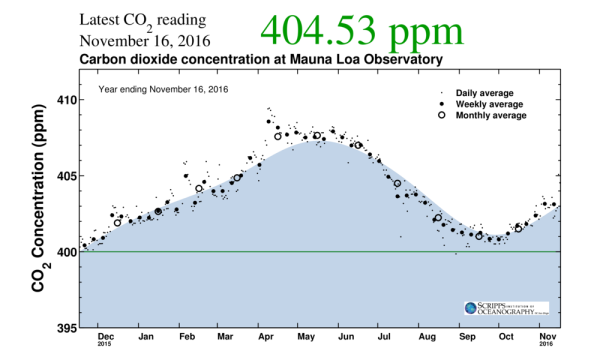

atmospheric carbon dioxide accumulation are spiking. For in

2016,the

world is now on track to see a record annual rate of atmospheric CO2

increase in the range of 3.2 to 3.55 parts per million.

(During

2015, atmospheric CO2 increased by a record annual rate of 3.05 ppm.

This happened during the build-up of one of the strongest El Ninos on

record. But as a weak La Nina settled in during late 2016 and

equatorial Pacific Ocean waters cooled, annual rates of carbon

dioxide accumulation is again on track to hit a new record high.

During mid-November, daily CO2 readings hit above 405 parts per

million. An indication that rates of accumulation had not at all

backed off from present record highs. Image source: The

Keeling Curve.)

This

rapid build-up is occurring despite a shift to La Nina — in which

somewhat cooler ocean surfaces tend to take in more atmospheric

carbon — and despite a

pause in the rate of carbon emissions increase from fossil fuel

related industry around the world.

The

Amazon as Surface Carbon Emissions Hot Spot

Large

equatorial forests like the Amazon are now producing hothouse gasses

rather than taking them in. In the

Copernicus Observatory’s surface

CO2 measure, we

find areas over the Amazon Rainforest where concentrations range

between 500 and 800 parts per million —

or up to nearly double the present average global atmospheric

concentration.

(Very

high surface CO2 concentrations over the Amazon Rainforest and West

Africa are an indication that key global carbon sinks aren’t

functioning. Instead, at least for the period of June through

November of 2016, they appear to be emitting very high volumes of

stored carbon back into the atmosphere. Image source: The

Copernicus Observatory.)

Desertifying

and drying forested regions of West Africa also show rather high

localized surface CO2 spikes. And both areas are among those

displaying highest

total column atmospheric CO2 concentrations.

According to NASA thermal monitoring, wildfires

are also quite extensive in these zones.

Meanwhile, the

global drought monitor indicates

that both the Amazon and West Africa have experienced exceptional

drought, not only for the most recent year, but over the past 4 years

through October of 2016. And it’s the combined drying and

burning that is likely pumping all that carbon out of soils and

forests.

Carbon

Sink Transitioning to Source

During

both 2005 and 2010, scientific

studies found that the Amazon briefly lost its ability to act as a

carbon sink.

Now, it appears that another period of a loss of functioning of the

‘world’s lungs’ has occurred. But in this case, the Amazon, and

parts of West Africa, appear to be consistently emitting carbon

dioxide rather than taking it in.

It

has long been a concern among climate scientists that human carbon

emissions at the rate of nearly 50 billion tons of CO2 equivalent

gasses each year would eventually harm the world’s forests, oceans,

lands, glaciers and permafrost zones’ ability to take in that

unprecedented carbon spike. And here we have at least some indication

that this has happened, at least during 2016 and hopefully not

extending over a longer period.

Links:

Hat

tip to Umbrios

Hat

tip to Andy in San Diego

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.