Climate Change Has Left Bolivia Crippled by Drought

“Bolivians

have to be prepared for the worst.”

— President

Evo Morales.

*****

23

November, 2016

Like

many countries, Bolivia relies on its glaciers and large lakes to

supply water during the lean, dry times. But as Bolivia has heated

with the rest of the world, those key stores of frozen and liquid

water have dwindled and dried up. Warming has turned the country’s

second largest lake into a parched bed of hardening soil. This heat

has made the country’s largest lake a shadow of its former expanse

and depth. It has forced Bolivia’s glaciers into a full retreat up

the tips of its northern mountains — reducing

the key Chacaltaya glacier to naught.

Multiple reservoirs are now bone-dry. And, for hundreds of thousands

of people, the only source of drinking water is from trucked-in

shipments.

Drought

Emergency Declared for Bolivia

After

decades of worsening drought and following a strong 2014-2016 El

Nino, Bolivia has declared a state of emergency. 125,000

families are under severe water rationing —

receiving supplies only once every three days. The water allocation

for these families is only enough for drinking. No more. Hundreds of

thousands beyond this hardest hit group also suffer from some form of

water curtailment. Schools have been closed. Businesses shut

down.60,000

cattle have perished. 149 million dollars in damages have racked

up. And

across the country, protests have broken out.

The

city of La Paz, which is the seat of Bolivia’s government and home

to about 800,000 people (circa 2001) has seen its

three reservoirs almost completely dry up.

The primary water reservior — Ajuan Kota — is

at just 1 percent capacity.

Two smaller reserviors stand

at just 8 percent.

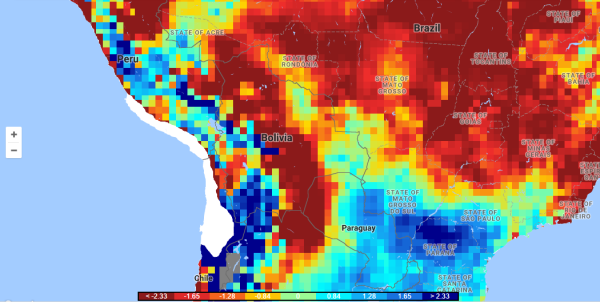

(Over

the past year, drought in Bolivia has become extreme — sparking

declarations of emergency and resulting in water rationing. It is the

most recent severe dry period of many to affect the state over the

past few decades. President

Morales has stated that climate change is the cause.

And the science, in large part, agrees with him. Image source: The

Global Drought Monitor.)

In

nearby El Alto, a city of 650,000 people (circa 2001), residents

are also suffering from water shortages. The

lack there has spurred unrest — with water officials briefly being

held hostage by desperate citizens.

As

emergency relief tankers wind through the streets and neighborhoods

of La Paz and El Alto, the government has established an emergency

water cabinet. Plans to build a more resilient system have been laid.

And foreign governments and companies have been asked for assistance.

But Bolivia’s larger problem stems from droughts that have been

made worse and worse by climate change. And it’s unclear whether

new infrastructure to manage water can deal with a situation that

increasingly removes the water altogether.

Dried

out Lakes, Dwindling Glaciers

Over

the years, worsening factors related to climate change have made

Bolivia vulnerable to any dry period that may come along. The added

effect of warming is that more rain has to fall to make up for the

resulting increased rate of evaporation. Meanwhile, glacial retreat

means that less

water melts and flows into streams and lakes during these hot, dry

periods.

In the end, this combined water loss creates a situation of drought

prevalence for the state. And when a dry period is set off by other

climate features — as happened with the strong El Nino that

occurred during 2014 to 2016 — droughts in Bolivia become

considerably more intense.

Ever

since the late 1980s, Bolivia

has been struggling through abnormal dry periods related to human

caused climate change.

Over time, these dry periods inflicted increasing water stress on the

state. And despite numerous efforts on the part of Bolivia, the

drought impacts have continued to worsen.

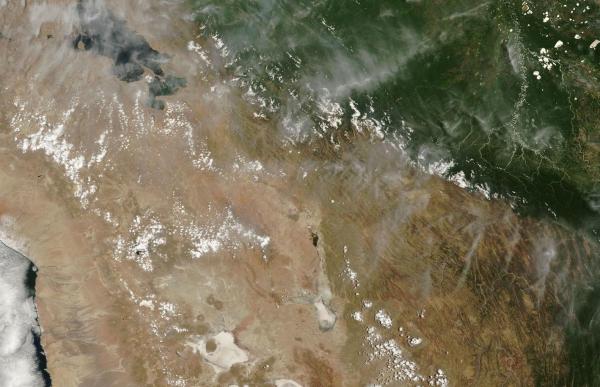

(In

this NASA satellite

shot of northern Bolivia taken on November 6, 2016, we find very thin

mountain snow and ice cover in upper center, a lake Titicaca that is

both now very low and filled with sand bars at upper left, and a

completely dried up lake Poopo at bottom-center. Bolivia relies on

these three sources of water. One is gone, and two more have been

greatly diminished. Scientists have found that global warming is

melting Bolivia’s glaciers and has increased evaporation rates by

as much as 200 percent near its key lakes. Image source: LANCE

MODIS.)

By

1994, added heat and loss of glaciers resulted in the country’s

second largest lake — Poopo — drying up. The lake recovered

somewhat in the late 1990s. But by early 2016, a lake that once

measured 90 x 32 kilometers at its widest points had again been

reduced to little more than a cracked bed littered with abandoned

fishing hulls. Scientists

researching the region found that the rate of evaporation in the area

of lake Poopo had been increased by 200 percent by global warming.

Bolivia’s

largest lake — Titicaca — is also under threat. From 2003 to

2010, the

lake is reported to have lost 500 square miles of surface water area.

During 2015 and 2016 drought near Titicaca intensified. In an act of

desperation, the government of Bolivia allocated

half a billion dollars to save the lake.

But despite this move, the massive reservoir has continued to shrink.

Now, the southern section of the lake is almost completely cut off by

a sand bar from the north.

In

the Andean mountains bordering Bolivia, temperatures

have been increasing by 0.6 degrees Celsius each decade.

This warming has forced the country’s glaciers into full retreat.

In one example, the Chacaltaya glacier, which

provided 30 percent of La Paz’s water supply,

had disappeared entirely by 2009. But the losses to glaciers overall

have been widespread and considerable — not just isolated to

Chacaltaya.

Intense

Drought Flares, With More to Come

By

December, rains are expected to return and provide some relief for

Bolivia. El Nino has faded and 2017 shouldn’t be as dry as 2015 or

2016. However, like many regions around the world, the Bolivian

highlands are in a multi-year period of drought. And the over-riding

factor causing these droughts is not the periodic El Nino, but the

longer-term trend of warming that is melting Bolivia’s glaciers and

increasing rates of evaporation across its lakes.

In

context, the current drought emergency has taken place as global

temperatures hit near 1.2 degrees Celsius hotter than 1880s averages.

Current and expected future burning of fossil fuels will continue to

warm the Earth and add worsening drought stress to places like

Bolivia. So this particular emergency water shortage is likely to be

just one of many to come. And only an intense effort to reduce fossil

fuel emissions can substantially slake the worsening situation for

Bolivia and for numerous other drought-affected regions around the

world.

Links:

Hat

tip to Colorado Bob

Hat

tip to ClimateHawk1

- Blazes have burnt 12,000 hectares, including five protected natural areas

- Endangered species under threat from fires that ‘took us by surprise’

Peru

has declared a state of emergency in seven districts in the north of

the country where forest fires have killed two, injured four and

burnt nearly 12,000 hectares (30,000 acres) of land, including five

protected natural areas.

Wildfires

have spread to 11 regions across the country, according to Peru’s

civil defence institute, in what scientists say may be the worst

drought in more than a decade.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.