You can bet your bottom dollar that the Guardian, while it points the finger at Vladimir Putin won't say a word about the Chocolate King - the corrupt war criminal

UKRAINE:

THE PRESIDENT’S OFFSHORE TAX PLAN

CCRP,

3

April, 2016

When

Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko ran for the top office in 2014,

he promised voters he would sell Roshen, Ukraine’s largest candy

business, so he could devote his full attention to running the

country.

“If

I get elected, I will wipe the slate clean and sell the Roshen

concern. As President of Ukraine I plan and commit to focus

exclusively on welfare of the nation,” Poroshenko told the German

newspaper Bild less than two months before the election.

Instead,

actions by his financial advisers and Poroshenko himself, who is

worth an estimated US$ 858 million, make it appear that the candy

magnate was more concerned about his own welfare than his country’s

– going so far as to arguably violate the law twice, misrepresent

information and deprive his country of badly needed tax dollars

during a time of war.

Poroshenko

did this by setting up an offshore holding company to move his

business to the British Virgin Islands (BVI), a notorious offshore

jurisdiction often used to hide ownership and evade taxes.

His

financial advisers say it was done through BVI to make Roshen more

attractive to potential international buyers, but it also means

Poroshenko may save millions of dollars in Ukrainian taxes.

In

one of several ironic twists in this story, the news about the

president’s offshore comes as the Ukrainian government is actively

fighting the use of offshores, which one organization says are

costing Ukraine US$ 11.6 billion a year in lost revenues.

The

Panama Papers

One

of the biggest leaks in journalistic history reveals the secretive

offshore companies used to hide wealth, evade taxes and commit fraud

by the world's dictators, business tycoons and criminals.

MORE

INFO

Details

about the Roshen deal can be found in the Panama Papers, documents

obtained from a Panama-based offshore services provider called

Mossack Fonseca. The documents were received by the German newspaper

Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared by the International Consortium of

Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) with the Organized Crime and

Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

And

in a more painful irony, the Panama Papers reveal that Poroshenko was

apparently scrambling to protect his substantial financial assets in

the BVI at a time when the conflict between Russia and Ukraine had

reached its fiercest.

The Law

Poroshenko’s

action might be illegal on two counts: he started a new company while

president and he did not report the company on his disclosure

statements.

According

to documents from Mossack Fonseca, on Aug. 4, 2014, George Ioannou,

then a senior associate of the law firm Dr. K. Chrysostomides &

Co LLC, sent an email to the Mossack Fonseca’s incorporation

department asking to register a new company for “a person involved

in politics.”

“The

company will be the holding company for his business … and will

have nothing to do with his political activities,” Ioannou wrote,

inquiring whether the registration agent would accept the job.

Seventeen

days later, a new company with Ukrainian origins was submitted to the

local registry of the British Virgin Islands.

href="https://www.occrp.org/en/panamapapers/ukraine-poroshenko-offshore/#"

data-toggle="modal" data-target="#lightbox"

style="box-sizing: border-box; color: rgb(148, 28, 30);

text-decoration: none; cursor: pointer; background-color:

transparent;"

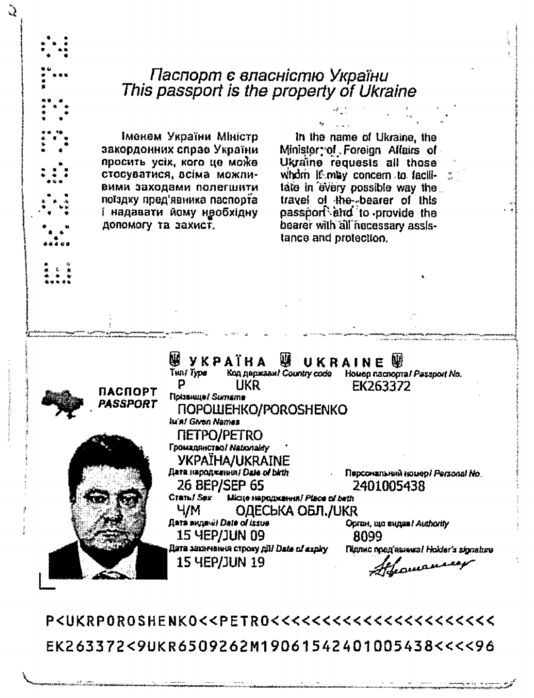

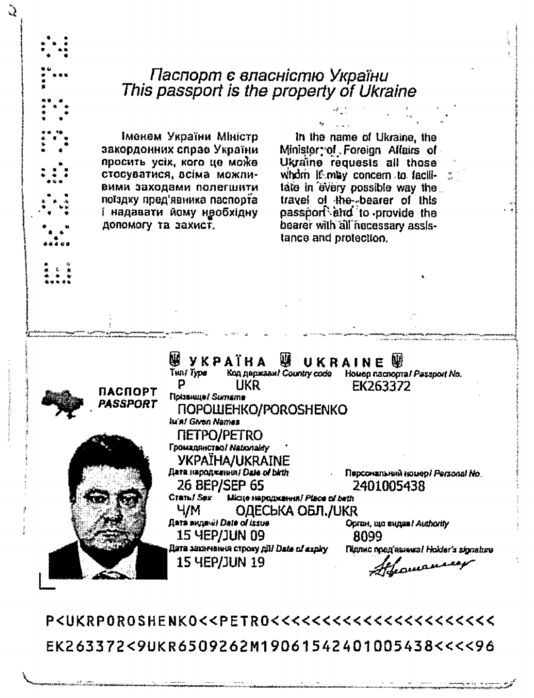

A scan of Petro Poroshenko's passport from Mossack Fonseca's internal files.

Called

Prime Asset Partners Ltd., a name similar to that of Poroshenko’s

Ukrainian holding company, it was located in the Akara Building in

Tortola, an address used by thousands of offshore companies from

around the world. The sole shareholder of the company was Poroshenko

with an address in Kyiv. A copy of his passport confirmed that the

beneficial owner was indeed the Ukrainian president.

Mossack

Fonseca records specify that Prime Asset Partners would serve as the

holding company for the Ukrainian and Cyprus companies of Roshen

confectionary corporation, with “proceeds from the business trade”

of the corporation being its source

of funds.

Oleksii

Khmara, executive director of Transparency International Ukraine,

told OCCRP that this is a big problem, calling it a conflict of

interest and apparent violation of both the constitution, which bans

the president from business activities, and the corruption laws,

which ban all public officials from conducting private business.

“If

a new business is created (after the election) and a public official

is listed as the beneficiary, that means he’s actively engaged in

business,” says Khmara. “This is a violation of the law, no

matter what the conditions (under which it’s registered) or the

jurisdiction used.”

The

president also failed to report the newly registered BVI company and

additional companies in his 2014 asset disclosure statements, a

second possible violation of the law. The information is also missing

on the 2015 asset forms. The Kyiv-based financial service group ICU

(the president’s financial advisers) disclosed

there were two more companies:

one in Cyprus called CEE Confectionery Investments Ltd., registered

in September 2014; and a second, registered in the Netherlands in

December 2014, called Roshen Europe B.V. The BVI holding company

holds the Cyprus company which in turn holds the Dutch company.

Meanwhile,

the president’s income

declaration for

that year gives no mention of either foreign income, or investment in

the statutory funds of foreign companies.

According

to an email from Makar Paseniuk, managing director of ICU, this is

because “shares in (BVI) Prime Asset Partners Limited have no par

value, and the declaration for 2014 required only shares having a par

value to be included.”

href="https://www.occrp.org/en/panamapapers/ukraine-poroshenko-offshore/#"

data-toggle="modal" data-target="#lightbox"

style="box-sizing: border-box; color: rgb(148, 28, 30);

text-decoration: none; cursor: pointer; background-color:

transparent;"

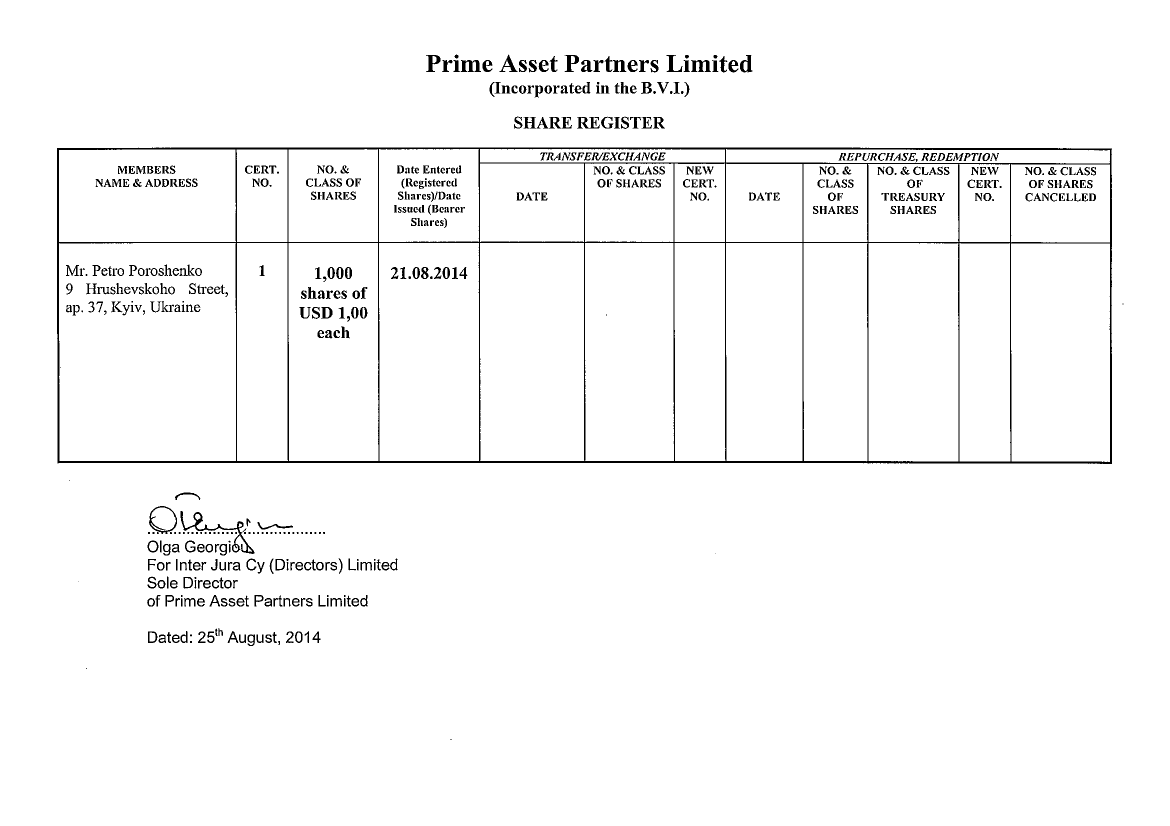

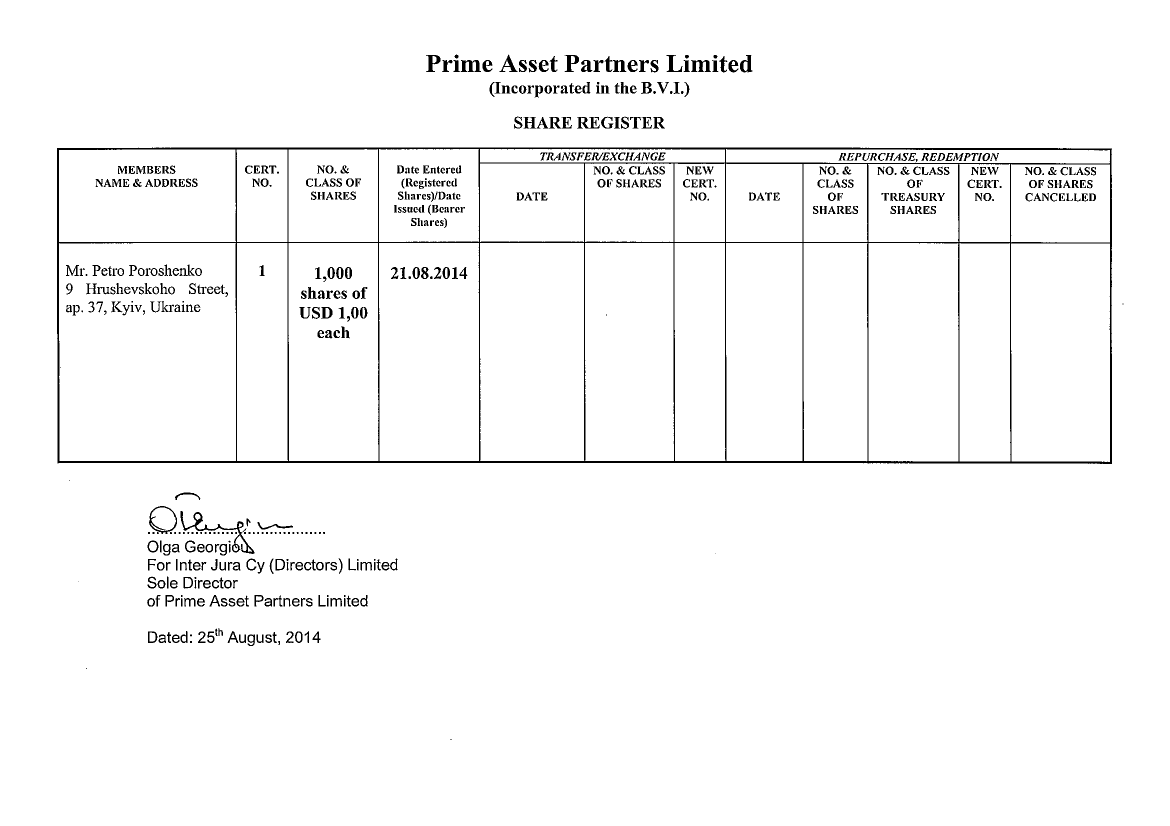

Share

Register for Prime Asset Partners Limited.

But

the documents obtained by OCCRP show that starting from the

registration date of Aug. 21, 2014, Prime Asset Partners Ltd.’s

shares indeed had a total value of US$ 1,000 and listed Poroshenko as

the sole shareholder. Its Cyprus subsidiary CEE Confectionary has

shares with the total value of €2,000,

while the Dutch Roshen Europe has

the statutory capital of US$85.

While the amounts are small, they still must be reported, experts

say. When Poroshenko’s advisers were asked about the discrepancy,

the advisers

told an OCCRP reporter that his information was inaccurate.

Had

the new president listed new foreign assets in his declarations at

such a critical time in Ukraine’s war with separatists, it might

have raised difficult questions for him.

Yevhen

Cherniak, an analyst with Transparency International Ukraine, looked

at information provided by OCCRP on the BVI, Cyprus and the

Netherlands’ companies established by Poroshenko and pointed out

that the president’s 2014 income declaration doesn’t say “a

single word about foreign companies” in the section disclosing

company shares.

Cherniak

said that the failure to disclose shares held by Poroshenko in the

BVI Prime Asset Partners Limited constitutes a “blatant”

violation of an administrative code article “Violation of Financial

Control Requirements,” which deals with the submission of false

information in income declarations by public officials, as provided

under the anticorruption law. He added that Poroshenko was only

liable for the violation for one year and that year passed on March

30 of this year, so he can’t be fined for 2014.

As

for the subsidiary companies in Cyprus and Netherlands, Cherniak

explained that the old anticorruption law, which was in place last

year, is vague about the term “beneficiary ownership.”

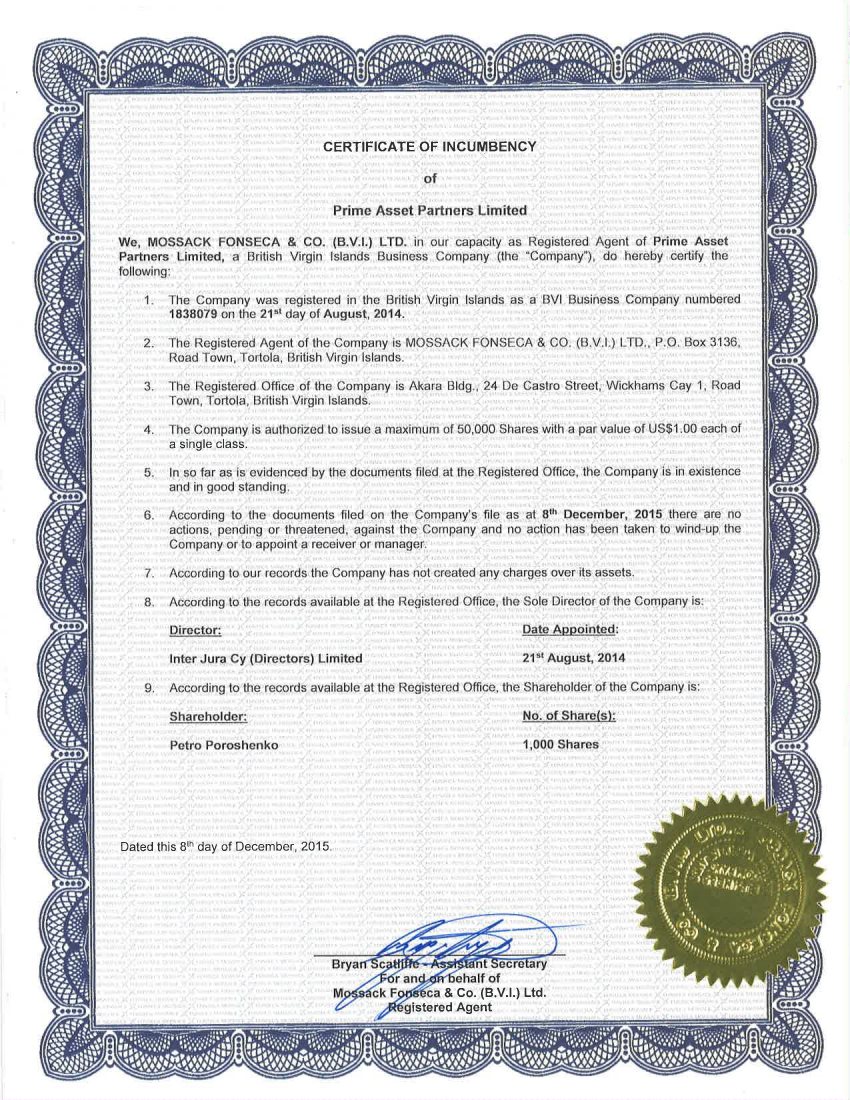

Certificate

from Mossack Fonseca asserting Poroshenko's ownership as of December

8, 2015.

The

president’s 2015

declaration published on April 1, 2016,

which was filed according to the old law, likewise makes no mention

of his BVI company, or foreign income from selling its shares.

According to the Panama Papers, he continued to be a direct

shareholder holding $1,000 worth of shares in the BVI Prime Asset

Partners Ltd as of December 8, 2015. No further changes to the

shareholding structure were recorded throughout the rest of 2015.

Poroshenko’s

adviser Paseniuk said in a March 22, 2016 response to OCCRP that when

the new law is enforced, “all companies beneficially owned by the

client will be properly declared.”

A Changing Story

Poroshenko

and his advisers have told an evolving story. His campaign-trail

promise to sell his company was soon dropped in favor of a plan to

create an independent trust to operate the company.

During

a news conference in Kyiv last January, Poroshenko said that in 2016

all his Roshen shares had been put in a blind trust managed by a

“respectable first-league foreign bank” which will “own,

control and manage the assets.” Even earlier, he made the same

claim in an interview with Deutsche Welle in November of 2015, saying

the trust was a done deal.

Those

statements now appear premature.

A

new story emerged when OCCRP was referred by the president’s office

to his financial advisers. Paseniuk’s response on behalf of the

president mentioned difficulties with the sale of Roshen corporation,

citing investors’ caution amid “the volatile geopolitical and

economic environment.” As a result, the offshore structure was

created to sell the president’s business and “improve

attractiveness of the Roshen group.”

Paseniuk

also told OCCRP that the trust was still a work in progress. “The

stake in Roshen will be transferred into a trust after all legal

formalities are completed,” he said.

He

said the BVI company has already set up subsidiaries in Cyprus and

the Netherlands, though none of them “holds any assets at the

moment.”

Regarding

the use of offshores, Paseniuk said “As a matter of practice,

Ukrainian businesses commonly use similar structures.”

On

March 21, a day before Paseniuk’s letter arrived, Ukraine’s

National Bank, and the country’s fiscal and anti-monopoly agencies

announced they had agreed to work jointly towards “de-offshorization”

of Ukrainian business.

According

to Global Financial Integrity, a Washington-based tax-haven watchdog,

between 2004 and 2013 Ukraine lost an average of US$ 11.6 billion a

year, due to illicit financial flows. In 2013, this equaled to nearly

a quarter of the country’s budget.

Why BVI?

OCCRP

spoke to legal and tax experts who said setting up a holding company

offshore – whether for trust purposes or sale – comes with a huge

tax advantage.

Daniel

Bilak, managing partner of the Kyiv office of the international law

firm CMS Cameron McKenna, did not discuss the specifics of

Poroshenko’s case but said saving on taxes is a key reason for

moving assets offshore and setting up a trust.

“Such

jurisdictions as the British Virgin Islands, Panama, and Malta are in

general considered offshores, because they have very flexible laws

for managing assets and company registration, while keeping maximum

confidentiality and minimal taxation,” Bilak says. “And this way

I’m allowed to limit paying taxes.”

Yaroslav

Lomakin, managing partner of the Honest&Bright consulting group

which operates in London, Moscow and Kyiv, calls setting up a

BVI-registered holding company the simplest and cheapest way to

protect assets, albeit “bad for image and reputation.”

“In

general, there is a presumption that trusts are created for better

protection of assets and lowering of tax obligations,” Lomakin

says. “The corporate income tax both for BVI and trusts is

approaching zero. While the most interesting and multi-level

(options) begin when it comes to profit distribution.”

But

just because politicians can sometimes create offshore trusts, should

they?

Andreas

Knobel, an expert with the Tax Justice Network, says

the potential problems with politicians and offshore holdings or

trusts can only be resolved by transparency. Any politician with a

trust shall “disclose the existence of a trust, the laws under

which it was created (to check if an abusive regime was chosen), and

… all trust assets to find out what companies, stocks are held

there.”

Knobel

adds that while in general incorporating a company in a tax haven may

be based on valid reasons such as lowering the tax rate or benefiting

from laxer laws, many will use them for tax avoidance, tax evasion or

corruption.

“It

would be interesting to inquire the reasons for establishing those

companies,” Knobel says. “Was it a tax reason? Secrecy? Why not

hold everything from Ukraine?”

The Kettle

Poroshenko

registered his companies during one of Ukraine’s darkest periods.

At

the end of July and early August of 2014, Ukrainians worried and

watched as Poroshenko called up reservists and warned of an invasion

by Russian troops. TV casualty reports were a daily reminder of the

war’s costs.

To

bolster the nation’s confidence, on July 26 Poroshenko invited the

media to a National Guard base to film him in camouflage fatigues

atop a new armored vehicle boldly firing its machine guns. His

commanders were deep in planning a bold counter-offensive designed to

reclaim parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts from separatists.

But

during those dark days, Poroshenko was also busy setting up his

offshore companies halfway around the world. On Aug. 4, 2014,

Poroshenko’s advisers started the registration procedures in the

BVI.

Also

in August, the Ukrainian general staff moved to recover territory

lost to separatists and ordered four volunteer battalions to enter

Ilovaisk, a key railway hub 40 kilometers from Donetsk.

The

plan was to cut a Russian supply line for the Donetsk-based

separatists. The command, however, failed to act on reports that a

force of 3,500 professional Russian troops had moved into the region.

On

August 21, 27 Ukrainian soldiers fell in what would become known as

the “Ilovaisk Kettle,” victims of intense Russian rocket

bombardments.

That

was the same day Poroshenko’s BVI holding company was officially

registered.

Within

a week, the Ukrainian battalions were encircled and their commanders

seemed unable to act for a number of critical days.

Khmara

says the president’s moral obligation should have been to put it on

hold.

“He

could’ve at least said ‘Boys, girls, don’t deal with this now –

we have more important issues to take care of,’” he said. “So

his silent consent… his inactivity at the time, contributed to this

moral crime.”

The

few weeks of fighting in the Kettle would lead to more deaths than in

any other battle – nearly 20 percent of the soldiers killed during

the war.

In

his response to OCCRP’s questions, Paseniuk said the transactions

were planned and agreed long before the military developments in

Ukraine and that the two events were unrelated.

On

September 1, 2014, Poroshenko announced Russia has openly attacked

Ukraine. On the same day he provided

Mossack Fonseca with a copy of his utility bill to

prove his home address.

Putin's cellist friend

Putin's cellist friend

Sergey

Roldugin leads a double life.

In

his public life, he’s a recognized master musician, a Russian

People’s Artist and professor. His other incarnation is as a

lifelong friend of Russian President Vladimir Putin. The

ramifications of that life, until today, have been hidden from the

world behind trusts and offshore companies that moved around billions

of dollars, funneled “donations” from Russia’s richest

businessmen into palaces and investments and controlled the

activities of strategic Russian enterprises.

In

a way, Roldugin has not been lying. He doesn’t have millions. He

has billions

Well, The Guardian mentioned Petro Poroshenko, but with explanatory first sentence :-)

ReplyDeletehttp://www.theguardian.com/news/2016/apr/04/panama-papers-ukraine-petro-poroshenko-secret-offshore-firm-russia

best,

Alex