Hothouse Gas Spikes to Extreme 409.3 Parts Per Million on April 10 — Record Rate of Atmospheric CO2 Increase Likely for 2016

11

April, 2016

Simply

put, a rapid atmospheric accumulation of greenhouse gasses is swiftly

pushing the Earth well outside of any climate context that human

beings are used to. The influence of an extreme El Nino on the world

ocean system’s ability to take down a massive human carbon emission

together with signs of what appears to be a significantly smaller but

growing emission from global carbon stores looks to be setting the

world up for another record jump in atmospheric CO2 levels during

2016.

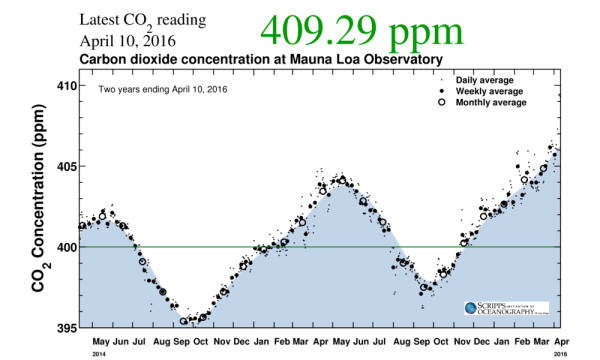

(See

the little dot well above the blue trend line on the upper right hand

portion of the above graph? That mark’s no accident. It represents

daily atmospheric CO2 readings of around 409.3 parts per million CO2

at the Mauna Loa Observatory on April 10 of 2016. It’s an insanely

high reading. But over the next two months we may see daily values

continue to peak in this range or hit even higher levels. Image

source: The

Keeling Curve.)

Already,

as we near the annual peak during late April through early May, major

CO2 spikes are starting to show up. On

Sunday, April 10 the Mauna Loa Observatory recorded a daily CO2

reading in the extraordinary range of 409.3 parts per million.

These readings follow March monthly averages near 405 parts per

million and precede an annual monthly peak in May that’s likely to

hit above 407 parts per million and may strike as high as 409 parts

per million. These are levels about 135 to 235 parts per million

above the average interglacial to ice age range for CO2 levels during

the relatively stable climate period of the last 2 million years.

In

other words — atmospheric CO2 levels continue to climb into

unprecedented ranges. Levels that are increasingly out-of-context

scary. For

we haven’t seen readings of this heat trapping gas hit so high in

any time during at least the past 15 million years.

2016

Could See Atmospheric CO2 Increase by 3.1 to 5.1 Parts Per Million

Above 2015

During

a ‘normal’ year, if this period of reckless human fossil fuel

burning can be rationally compared to anything ‘normal,’ we’d

expect CO2 levels to rise by around 2 parts per million. Such a jump

in the 2015 to 2016 period would result in monthly averages peaking

around 406 parts per million by May. However, with a record El Nino

and other influences producing large areas of abnormally warm sea

surfaces, the world ocean’s ability to draw down both the massive

human emission and the apparently much smaller, but seemingly

growing, global carbon feedback has been hampered.

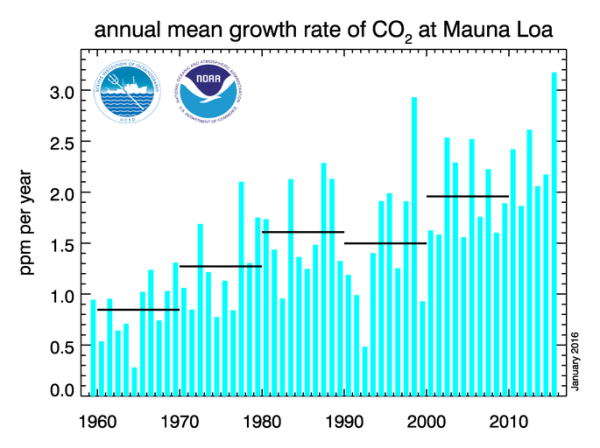

(Annual

mean CO2 growth rate for 2016 is likely to hit even higher than

records seen during 2015 due to the influence of a record El Nino on

the world ocean system’s ability to draw down excess atmospheric

carbon and due to the fact that global CO2 emission remain near

record high levels set in 2014. Image source: NOAA

ESRL.)

In

1998, during a then record El Nino and at a time when global carbon

emissions from human sources were significantly lower than they are

today and during a period when the global carbon stores appeared to

be mostly dormant, atmospheric CO2 levels rose by a then record 2.9

parts per million. During 2015, as a record El Nino ramped up and as

the global carbon stores continued their ominous rumbling, annual

average increases hit a new high of 3.05 parts per million. But with

the strongest El Nino impacts hampering ocean carbon draw-down

extending on into the current year, it appears that 2016 average

rates of atmospheric CO2 increase are likely to be even higher. Due

to this, hopefully temporary, reduction in the ocean’s ability to

take in atmospheric carbon, we’re likely to see May 2016 CO2 levels

at Mauna Loa hit a range of 3.1 to 5.1 parts per million (407 to 409

ppm in total) above previous record high levels of around 403.9 parts

per million for the same month during 2015.

The

Last Time CO2 Values Were So High Was During the Middle Miocene —

15 Million Years in the Earth’s Deep Past

By

any yardstick, these are extreme annual rates of atmospheric CO2

increase. Rates

that are likely at least an order of magnitude faster than during the

last hothouse extinction — the PETM — 55 million years ago.

Just a few years ago, the scientific bodies of the world voiced

serious concern about atmospheric CO2 levels equaling those seen

during the Pliocene period — a geological epoch 3-5 million years

ago when Earth temperatures were 2-3 C warmer than they are today and

atmospheric CO2 levels ranged between 390 and 405 parts per million.

But in just a brief interval, we’ve blown past that potential

paleoclimate context and into another, more difficult, much warmer,

world. A period further back into the great long ago when human

civilization as it is today couldn’t have been imagined and a

species called homo sapiens had millions of years yet to even begin

to exist.

(For

the week ending April 10, it appears that atmospheric CO2 levels have

already averaged above 407 parts per million. Over the next two

months, global atmospheric levels will reach new record highs likely

in the range of 407 to 409 parts per million in the monthly values

representing an extreme jump in readings of this key heat trapping

gas. Image source:NOAA

ESRL.)

For

it’s been about 15 million years since we’ve seen atmospheric

values of this critical greenhouse gas hit levels so high.

Back then, the Earth was about 3-5 degrees Celsius hotter than the

19th Century and oceans were about 120 to 190 feet higher.

Maintaining current greenhouse gas levels in this range for any

extended will risk reverting to climate states similar to those of

the Middle Miocene past — or potentially warmer if global carbon

stores laid down during the period of the last 15 million years of

cooling are again released into the Earth’s ocean and atmosphere.

At

current annual rates of atmospheric CO2 increase, it will take

between 20 and 50 years to exceed the Miocene and Ogliocene range of

405 to 520 parts per million CO2. At that point, we would be hitting

CO2 levels high enough to wipe out most or all of the glacial ice on

Earth. That’s basically what happens if we keep burning fossil

fuels as we are now for another few decades.

In

any case, it’s worth noting that 2016’s potential annual

atmospheric CO2 increase of between 3.1 and 5.1 parts per million is

extraordinarily bad. Something we shouldn’t be doing to the Earth’s

climate system. There really is no other way to say it. Such rates of

hothouse gas increases are absolutely terrible.

Links:

Hat

Tip to June

Hat

Tip to Kevin Jones

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.