With Temperatures Hitting 1.2 C Hotter than Pre-Industrial, Drought Now Spans the Globe

30

November, 2016

Jeff

Goodell, an

American author and editor at Rolling Stone,

is noted for saying this: “once we deliberately start messing with

the climate, we could inadvertantly shift rainfall patterns (climate

models have shown that the Amazon is particularly vulnerable) causing

collapse of ecosystems, drought, famine and more.”

We

are in the process of testing that theory. In the case of drought,

which used to just be a regional affair but has now gone global,

Goodell appears to have been right on the money.

****

According

to a recent report by the World Meteorological Organization,

the Earth is on track to hit 1.2 degrees Celsius hotter than

pre-industrial temperatures during 2016. From sea-level rise, to

melting polar ice, to extreme weather, to increasing numbers of

displaced persons, this temperature jump is producing steadily

worsening impacts. Among the more vivid of these is the current

extent of global drought.

The

Four-Year Global Drought

During

El Nino years, drought conditions tend to expand through various

regions as ocean surfaces heat up. From 2015 to 2016, the world

experienced a powerful El Nino. However, despite the noted influence

of this warming of surface waters in the Equatorial Pacific, widely

expansive global drought extends back through 2013 and farther.

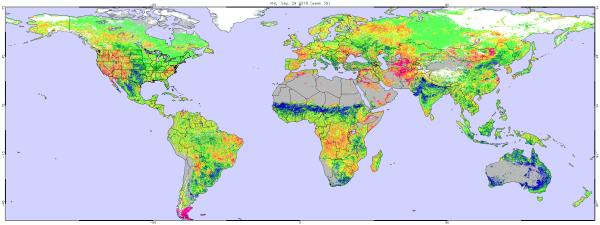

(The

Global Drought Monitor finds that dry conditions have been prevalent

over much of the globe throughout the past four years. For some

regions, like the Colorado River area, drought has already extended

for more than a decade. Image source: SPEI

Global Drought Monitor.)

In

the above image, we see soil moisture deficits over the past 48

months. What we find is that large sections of pretty much every

major continent are undergoing at least a four-year drought. Drought

conditions were predicted by climate models to intensify in the

middle latitudes as the world heated up. It appears that this is

already the case, but the Equatorial zone and the higher latitudes

are also experiencing widespread drought. If there is a detectable

pattern in present conditions, it is that few regions have avoided

drying. Drought is so wide-ranging as to be practically global in its

extent.

Widespread

Severe Impacts

These

drought conditions have noted impacts.

In

California alone, more

than 102 million trees have died due

to rising temperatures and a drought that has lasted since 2010. Of

those, 62 million have perished just this year. Drought’s

relationship to tree mortality is pretty simple — the longer

drought lasts, the more trees perish as water stores in roots are

used up. California has, so far, lost 2.5 percent of its live trees

due to what is now the

worst tree mortality event in the state’s history.

(It’s

not just California. Numerous regions around the world show plants

undergoing life-threatening levels of stress. In the above map,

vegetative health is shown to be moderately stressed [yellow] to

severely stressed [pink] over broad regions of the world. Image

source:Global

Drought Information System.)

The

California drought is just an aspect of a larger drought that

encompasses much of the North American West.

For the Colorado River area, this includes a 16-year-long drought

that has pushed Lake Mead to its lowest

levels ever recorded.

With rationing of the river’s water supplies looming if a

miraculous break in the drought doesn’t suddenly appear, states are

scrambling to figure out how to manage a worsening scarcity.

Meanwhile, reports indicate that cities

like Phoenix will require executive action on the part of the

President to ensure water supplies to millions of residents over

the coming years, should conditions fail to improve.

Further

east, drought has flickered on and off in the central and southern

U.S.In

the southeast, a

flash drought has

recently helped to spur an unseasonable spate of wildfires over the

Smoky Mountain region. Yesterday, at Gaitlinburg, TN, raging flames

fed by winds ahead of a cold front forced 14,000 people to evacuate,

damaged or destroyed 100 homes, and took three lives.

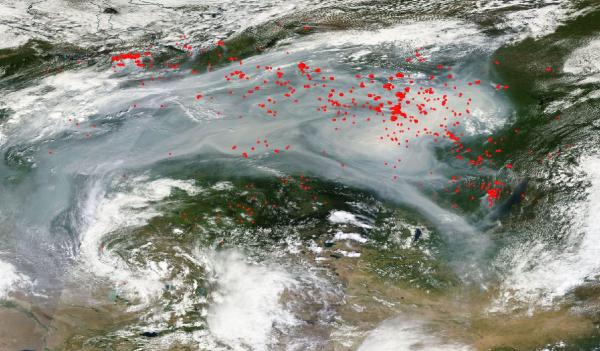

(Siberian

wildfires burning on July 23, 2016 occur in the context of severe

drought. Image source: LANCE

MODIS.)

In

the upper northern latitudes, the primary upshot of drought has also

been wildfires.

Wildfires are often fanned by heat and drought in heavily forested

regions that see reduced soil moisture levels. Thawing permafrost and

reduced snow cover levels exacerbate the situation by further

reducing moisture storage in dry regions and by adding peat-like

fuels for fires.

From

Alaska to Canada to Siberia, this has increasingly been the case.

Last year, Alaska

experienced one of its worst wildfire seasons on record.

This year, both

heat and drought contributed to the severe fires raging around the

Fort McMurray region in Canada.

And over recent years, wildfires running through a tremendously dry

Siberia have been so extreme that

satellites orbiting one million miles away could detect the smoke

plumes.

Drought

and wildfires in or near the Arctic justifiably seem odd, but when

one considers the fact that many climate models had predicted that

the higher northern latitudes would be one of the few major regions

to experience increases in precipitation, that oddity turns ominous.

If the present trend toward widespread Arctic drought is

representative, then warming presents a drought issue from Equator to

Pole.

A

dwindling Lake Baikal — which feeds on water flowing in from rain

and snow in Central Siberia — bears grim testament to an expanding

drought over central and northern Russia. Lake

Baikal, the world’s deepest and oldest lake, is threatened by

climate change-related drying of the lands that drain into

it. In

2015, water levels in Baikal hit record-low levels,

and over the past few years, fires

raging around the lake have increasingly endangered local communities

and wildlife.

To

the south and west, the

Gansu province of China was placed under a level 4 drought alert this

past summer. There,

large swaths of crops were lost; half a billion dollars in damages

mounted. The Chinese government rushed aid to 6.2 million affected

residents, trucking potable water into regions rendered bereft of

local supplies.

(Lakes

and river beds dried up across India earlier this year as the monsoon

was delayed for the third year in a row. Image source: India

Water Portal.)

India

this year experienced similar, but far more widespread, water

shortages. In April, 330

million people within India experienced water stress.

Water resupply trains wound through the countryside, delivering

bottles of potable liquid to residents who’d lost access. A return

of India’s monsoon provided some relief, but drought in India and

Tibet’s highlands remains in place as glaciers shrink in the

warming air.

Africa

has recently seen various food crises crop up as wildfires raged

through its equatorial forests. Stresses

to humans, plants, and animals due to dryness, water and food

shortage, and fires have been notably severe. Earlier

this year, 36

million people across Africa faced hunger due to drought-related

impacts.

Nearer term, South Africa has been forced

to cull hippo and buffalo herds as

a multi-year drought continues there.

Shifting

north into Europe, we also find widespread and expanding drought

conditions. This situation

is not unexpected for Southern Europe, where global climate models

show incursions of desert climates from across the Mediterranean. But

as with northern Russia and North America, Northern Europe is also

experiencing drought. These droughts across Europe helped to

spark severe wildfires in Portugal and Spain in

the summer, as corn

yields for the region are predicted to fall.

(During

November, drought spurred wildfires that erupted along the Amazon

Rainforest’s boundary zone in Peru. Image source: LANCE

MODIS.)

Finally

finding our way back into the Americas, we see widespread drought

conditions covering much of Brazil and Columbia, winding down the

Andes Mountains through Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina. In

sections of the increasingly clear-cut and fire-stricken Amazon

Rainforest and running on into northeastern Brazil, drought

conditions have now lasted for five years.

There, half of the region’s cities face water rationing and more

than 20 million people are currently confronted with water stress.

From September to November 2015, more

than 100,000 acres of drought-stricken Amazonian rainforest has

burned in Peru.

Meanwhile, Bolivia

has seen its second-largest lake dry up and critical water-supplying

glaciers melt as hundreds of thousands of people fall under water rationing.

Impacts

to Food

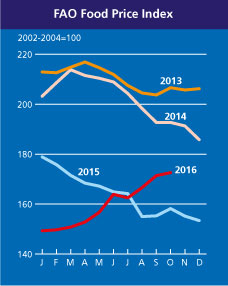

Ongoing

drought and extreme weather have created local impacts to food

supplies in various regions. However, these impacts have not yet

seriously affected global food markets. Drought in Brazil and

India, for example, has significantly impacted sugar production,

which in turn is pushing global food prices higher. Cereal production

is a bit off which is also resulting in higher prices, though not the

big jumps we see in sugar. But a Food and Agricultural Organization

(FAO) Index for October of 2016 (173 approx) at 9 percent higher than

last year’s measure for this time of year is still quite a ways off

the 229 peak value during 2011 that helped to set off so much unrest

around the globe.

(Rising

food prices during 2016 in the face of relatively low energy prices

and significant climate-related challenges to farmers is some cause

for concern. Image source: FAO.)

That

said, with energy prices falling into comparatively low ranges,

relatively high (and rising) food prices are some cause for concern.

Traditionally, falling energy prices also push food prices lower as

production costs drop, but it appears that these gains by farmers are

being offset by various environmental and climate impacts.

Furthermore, though very widespread, drought appears to have thus far

avoided large grain-producing regions like the central U.S., and

central and east Asia. So the global food picture, if not entirely

rosy, isn’t as bad as it could be.

Conditions

in Context — Increasing Evaporation, Melting Glaciers, Less Snow

Cover, Shifting Climate Zones

With

the world now likely to hit 1.5 C above pre-industrial temperatures

over the next 15 to 20 years, overall drought conditions will

likely worsen. Higher rates of evaporation are a primary

feature of warming, meaning more rain must fall just to keep pace. In

addition, loss of glacial ice in various mountain ranges and loss of

snow cover in drier Arctic and near-Arctic environments will further

reduce river levels and soil moisture. Increasing prevalence of

extreme rainfall events versus steady rainfall events will further

stress the vegetation that aids in soil moisture capture. Finally,

changes to atmospheric circulation due to polar amplification will

combine with a poleward movement of climate zones to generally

confuse traditional growing seasons. As a result, everything that

relies on steady water supplies and predictable weather patterns will

face challenges as the world shifts into a state of more obvious

climate change.

Links:

Hat

tip to ClimateHawk1

Hat

tip to June

Hat

tip to Ryan

Hat

tip to Griffon

Hat

tip to Suzanne

Hat

tip to Cate

Hat

tip to Colorado Bob

Hat

tip to Greg

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.