More evidence of infrastructure coming under strain because of the extreme flooding that is not going away

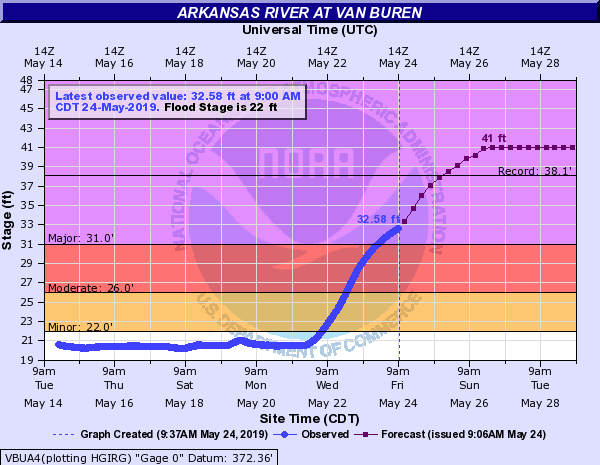

Biggest flood on record is coming this weekend to Fort Smith/Van Buren AR on the Arkansas River--projected to be nearly 3 feet above the previous record crest (Apr 16, 1945) water.weather.gov/ahps2/hydrogra…

Record-breaking floods inundate parts of central US

Accuweather,

24

May, 2019

Evacuations

are underway as flooding is

impacting areas across Oklahoma, Kansas, Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois

and parts of Nebraska and Iowa.

The

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is warning Arkansans about the

possibility of historic flooding along the Arkansas River.

Dardanelle, Arkansas, has been one of the more recent cities to face

the floodwaters, the Arkansas River at this point reaching nearly 36

feet at 3 p.m. CDT on Saturday. Evacuations are also underway in Fort

Smith, Arkansas. Gov. Asa Hutchinson declared a state of emergency on

Friday.

Officials

in Tulsa, Oklahoma are also urging

some residents to prepare to evacuate and move to higher

ground as the expected rain will threaten already stressed levees.

On

Friday afternoon, water began flowed over the emergency spillway at

Elk City Lake, reported in a tweet.

Greenwood county authorities have called for the evacuation of

residents who live below the Fall River Dam according to a local

news source.

Three fatalities have been reported as a result of the flooding. One driver attempted to cross a flooded roadway in Perkins, Oklahoma, and two other bodies were found in a submerged vehicle near the Mississippi River in Missouri.

According

to AccuWeather Meteorologist Kristina Pydynowski, there are rainfall

estimates of over 8 inches in the last seven days across northeastern

Oklahoma, southwestern Missouri and southeastern Kansas.

"So

far this month, 10 inches of rain has soaked Tulsa, Oklahoma. The

city averages nearly 6 inches for the entire month," Pydynowski

said.

On Wednesday, two barges became loose during flooding on the Arkansas River. The town of Webbers Falls called for its 600 residents to evacuate.

"One

can only guess what this Arkansas River flood crest would be like

without the many flood-control dams and lakes upstream to hold back

at least some runoff," Andrews said.

The

Army Corps of Engineers continues to release 250,000

cubic feet of water per second from Keystone Dam into the

Arkansas River and this level is expected to hold steady into

Wednesday, May 29. Previously, the level was supposed to lessen on

Sunday, May 26, but this changed Saturday morning as

announced by Tulsa, Oklahoma Mayor G.T. Bynum.

Due

to the additional release at Keystone Dam, flood water is steadily

rising and residents and businesses along the Arkansas River need to

heed all warnings and take precautions.

The

excessive flow comes as water from flood control lakes in Oklahoma

and Kansas is released into the Arkansas River.

"One

can only guess what this Arkansas River flood crest would be like

without the many flood-control dams and lakes upstream to hold back

at least some runoff," Andrews said.

The

Army Corps of Engineers continues to release 250,000

cubic feet of

water per second from Keystone Dam into the Arkansas River and this

level is expected to hold steady into Wednesday, May 29. Previously,

the level was supposed to lessen on Sunday, May 26, but this changed

Saturday morning as

announced by

Tulsa, Oklahoma Mayor G.T. Bynum.

Due

to the additional release at Keystone Dam, flood water is steadily

rising and residents and businesses along the Arkansas River need to

heed all warnings and take precautions.

The

flood gauge near Ponca City, Oklahoma, on the Arkansas River crested

at 22.26 feet on Friday, breaking the 1993 record of 20.11 ft.

All

residents should stay out of the water, adhere to traffic diversions,

and maintain a close watch on children. The Tulsa Police Department

has already had to remove people from the areas along the Arkansas

River.

Bynum reminded

parents not to let their children run around or play in

floodwaters, as it could put both them and first responders at risk.

And this...

Mississippi Floodway May Be Opened for Third Time in History

A major barrier that keeps the Mississippi River in its current path may be opened for just the third time in its history, potentially flooding a large part of rural Louisiana.

Concern is growing that heavy rains will cause the Mississippi to flood over the top of the Morganza Floodway -- a long dam-like structure that is designed to divert 600,000 cubic feet per second of water to take pressure off the river. To prevent that, the Army Corps of Engineers may be forced to open the gates of the barrier.

The river has been high or flooding since last October, engorged by huge rainfalls that have slowed crop planting in the Great Plains and the upper Midwest. The Mississippi between New Orleans and Baton Rouge is lined with energy infrastructure including refineries, and the swell has caused shipping delays in the waterway, a main route for grain, chemicals, coal and oil.

There’s a risk that the river will flood over the Morganza by about June 5, which would render it useless, said Ricky Boyett, a spokesman for the Army Corps of Engineers. To avoid that, its 125 gates will have to start opening by June 2 at the latest, he said.

“The decision to open Morganza Spillway has not been made yet,” said Jean Kelly, a spokeswoman for the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality. The state’s governor, John Bel Edwards, is scheduled to hold a press conference this afternoon, according to local media.

Evacuations underway in parts of Greenwood Co. due to water release

KWCH,

24 May, 2019

GREENWOOD COUNTY, Kan. (KWCH) Evacuations are underway in parts of Greenwood County as record levels of water are being released out of Fall River Reservoir.

Greenwood County Emergency Management are urging residents to stay away from Fall River and the City of Fall River, south of the Fall River dam. They say the dam is releasing 36,000 cubic feet of water per second.

"Record levels of water are being released out of Fall River Reservoir that will cause widespread flooding, the Greenwood County Sheriff's Office said.

The county is currently conducting assessments and identifying significant damages that need emergency repairs. They are estimating it will take months to repair roads.

Officials say search and rescue operations are underway for people in the area. A shelter is set up in Eureka at Jefferson Street Baptist Church, 300 S. Jefferson Street.

America's Achilles' Heel: the Mississippi River's Old River Control Structure

May 10, 2019, 7:03 AM EDT

| Above: Aerial view of the four structures of the Mississippi River Old River Control Structure, looking downstream to the south. Water flows from the Mississippi River through the four structures, to the Atchafalaya River (right). Image credit: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. |

10 May, 2019

America

has an Achilles' heel. It lies on a quiet, unpopulated stretch of the

Mississippi River in Louisiana, 45 miles upstream from Baton Rouge.

Rising up from the flat, wooded west flood plain of the Mississippi

River are four massive concrete and steel structures that would make

a pharaoh envious: the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ greatest work,

the two billion-dollar Old River Control Structure (ORCS). The ORCS

saw its second highest flood on record in March 2019, and flood

levels have risen again this week to their fifth highest level on

record. While the structure is built to handle the unusual stress

this year's floods have subjected it to, there is reason for concern

for its long-term survival, since failure of the Old RIver Control

Structure would be a catastrophe with global impact.

This

first part of a 3-part series will study the history and importance

of this critical structure, and how it almost failed in 1973. Part

II, scheduled to run on Monday, is titled, Escalating Flood

Heights Puts Mississippi River’s Old River Control Structure at

Increasing Threat of Failure. Part III is titled, If

the Old River Control Structure Fails: A Catastrophe With

Global Impact, and will run later next week.

|

| Figure 1. Louisiana as seen by the MODIS instrument on March 21, 2019, showing the location of the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers, plus the Old River Control Structure, which diverts 30% of the flow of the Mississippi into the Atchafalaya. Floods of the two rivers were creating large sediment plumes in the Gulf of Mexico. Image credit NASA. |

Chaining the Mississippi to its current channel

This

marvel of modern civil engineering has, for fifty-five years, done

what many thought impossible—impose man's will on the Mississippi

River. Mark Twain, who captained a Mississippi river boat for many

years, wrote in his book Life

on the Mississippi,

"ten thousand river commissions, with the mines of the world at

their back, cannot tame that lawless stream, cannot curb it or define

it, cannot say to it 'Go here,' or Go there, and make it obey; cannot

save a shore which it has sentenced; cannot bar its path with an

obstruction which it will not tear down, dance over, and laugh at."

The great river wants to carve a new path to the Gulf of Mexico; only

the Old River Control Structure keeps it at bay.

Failure

of the Old River Control Structure and the resulting jump of the

Mississippi to a new path to the Gulf would be a severe blow to

America's economy, robbing New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and the critical

industrial corridor between them of the fresh water needed to live

and do business. Since a huge portion of our imports and exports ship

along the Mississippi River, a closure would cost $295 million per

day, said

Gary LaGrange, executive

director of the Port of New Orleans, during the great flood of 2011.

An extended closure of the Lower Mississippi to shipping might cost

tens of billions. Since barges on the Mississippi carry 60% of U.S.

grain to market, a long closure of the river to barge traffic could

cause a significant spike in global food prices, potentially

resulting in political upheaval like the “Arab Spring” unrest in

2011, and the specter of famine in vulnerable food-insecure nations

of the Third World.

|

| Figure 2. Two views of the Mississippi River. Left: the meander paths of the Mississippi over time, as published in "Geological Investigation of the Alluvial Valley of the Lower Mississippi River" (Harold N. Fisk, 1944, available online). Right: The Army Corps of Engineers' view of Mississippi River, with peak flow rates in cubic feet per second for a maximum 1-in-500-year "Project Flood”. The Corps has straightened the river’s path by cutting off meander bends, and has built multiple flood control structures capable of diverting a portion of the river's flow. |

A shorter and steeper path to the Gulf

The

mighty Mississippi River keeps on rollin' along its final 300 miles

to the Gulf of Mexico south of New Orleans—but unwillingly. There

is a more attractive way to the Gulf—150 miles shorter, and more

than twice as steep. This path lies down the Atchafalaya River, which

connects to the Mississippi at a point 45 miles north-northwest of

Baton Rouge, 300 river miles from where the river empties into the

Gulf of Mexico southeast of New Orleans.

Each

year, the path down the Atchafalaya grows more inviting. As the

massive amounts of sediment the Mississippi carries—scoured from

fully 41% of the continental U.S. land area, plus a portion of

southern Canada—reach the Gulf of Mexico, the river's path grows

longer. This forces it to dump large amounts of sediment hundreds of

miles upstream, in order to build its bed higher and maintain the

flow rates needed to flush such huge amounts of sediment to the sea.

Thus, the difference in elevation between the bed of the Mississippi

and the Atchafalaya—currently about 17 - 19 feet at typical flow

rates of the rivers—grows ever steeper, and the path to the Gulf

down the Atchafalaya more appealing.

The

two highest floods on record at the Old River Control Structure

occurred in 2011 and 2019, and the 2018 flood ranked as the fourth

highest on record. Floods like these further increase the slope, as

flood waters scour out the bed of the Atchafalaya. Without the Old

River Control Structure, the Mississippi River would have carved a

new path to the Gulf in the 1970s, leaving Baton Rouge and New

Orleans stranded on a salt water estuary, bereft of their main source

of fresh water to supply their people and industry.

History of Old River

The

Mississippi River has been carving a path to the ocean since time

immemorial, always seeking the shortest and steepest route possible.

Approximately once every 1000 years, the river jumps out of its banks

and carves a new path to the sea. The Mississippi has been flowing

along its current course past New Orleans since about 1000 A.D., but

beginning in the 1800s, the Mississippi began slowly shifting more

and more of its flow down the Atchafalaya River, along the path it

used to take to the Gulf about 3000 years ago.

This

diversion accelerated in 1831, when steamboat captain Henry Miller

Shreve used his steam-powered snag boat Heliopolis to

dredge a new channel for the Mississippi River. Shreve cut off a huge

meander bend which shortened navigation of the Mississippi River by

18 miles and shifted the main channel 6 miles to the east. The two

arms of the old severed meander created what is now called Old River,

which connects the Mississippi to the Atchafalaya. The clearing of an

ancient 40-mile-long log jam on the Atchafalaya in the 1840s, to

allow navigation on the river for the first time, further increased

the flow of water coming down the river from the Mississippi.

|

| Figure 3. October 20, 1937: German-Swiss-US mathematical physicist Albert Einstein (1879 - 1955) (left) being greeted by his son Hans Albert on arrival at New York. In the 1950s, the younger Einstein helped with the design of the Old River Control Structure. Image credit: Keystone/Getty Images. |

Building the Old River Control Structure

By

the early 1950s, the Atchafalaya had captured over 20% of the

Mississippi River’s flow, and the Army Corps of Engineers grew

concerned that the Mississippi might change course as early as 1968.

One of the experts that they called in to help study the problem was

one of the world’s leading authorities on river sediment transport:

UC-Berkeley hydraulic engineer Dr. Hans Albert Einstein, son of the

famous Albert Einstein. With Hans Albert Einstein’s help, the Corps

drew up the design for the Old River Control Structure, and

construction began in the late 1950s. The structure resembled a dam

with gates to control the amount of water escaping from the

Mississippi to the Atchafalaya. This "Low Sill Structure",

completed in 1963, consisted of a 566-foot-long dam with 11 gates,

each 44 feet wide, that could be raised or lowered to control the

amount of flow leaving the Mississippi. A companion "Overbank

Structure" was built on dry land next to the Low Sill Structure,

in order to control extreme water flows during major floods. The

total cost of the two structures: about $560 million (2019 dollars).

|

| Figure 4. In 1987, after the newly-built Auxiliary Structure began operating, the Army Corps drained the channel to the Low Sill Structure and repaired some of the damages incurred in the 1973 flood. Above, we see the outflow side of the structure. The Low Sill Structure was designed to withstand a 37-foot difference in water levels (“head”) between the higher Mississippi River and the lower Atchafalaya River. Due to permanent damages to the structure during the 1973 flood, engineers determined that a safe differential in water surfaces on either side of the structure should be no more than 22 feet. Image credit: USACE. |

The flood of 1973: Old River Control Structure almost fails

For

the first ten years after completion of the Old River Control

Structure, no major floods tested it, leading the Army Corps to

declare, "We

harnessed it, straightened it, regularized it, shackled it." But

the structure underwent a severe battering during the flood of 1973,

one that left it permanently damaged. During the fall and winter of

1972, exceptionally heavy rains fell throughout the Tennessee and

Lower Mississippi Valley, saturating the soil and raising the level

of the river. Then in early March, prodigious rains hit the

watersheds of the Missouri and Upper Mississippi, and the Corps knew

they might be facing a Project Flood—the maximum flood

theoretically possible. The situation worsened in April, when an

usually heavy snowpack in the Rockies melted suddenly, sending a

massive pulse of flood waters down the Missouri and Arkansas rivers.

When more heavy rains hit the Mississippi Valley in late March, the

Mississippi River rose to dangerously high levels, forcing the

opening of the Bonnet Carré Spillway for the first time in 23 years.

During

this period, the Low Sill Structure was operated at more than 50

percent of a Project Flood flow—half a million cubic feet per

second. The Army Corps began preparations to open the nearby Morganza

Floodway to take pressure off of the Old River Control Structure, and

promised to give five days of warning before opening the floodway.

But as it turned out, it would have to be opened with very little

warning.

|

| Figure 5. The Old River Control Structure’s Low Sill Structure as seen in April 1973. Turbulence from a major flood caused the 67-foot long southern wing wall on the intake channel leading to the Mississippi River to collapse on April 14, and a large eddy can be seen where the wall used to be. The eddy helped scour out a football field-sized hole up to 50 feet deep that undermined 7 of the structure’s 11 gates and nearly caused its failure. A ramp leading to the eddy was built, and an emergency stone replacement dike was built. Image credit: USACE. |

James

Barnett Jr.’s fantastically detailed 2017 book Beyond

Control: The Mississippi River's New Channel to the Gulf of

Mexico tells the story of how on April 14, 1973,

the Old River Control Structure foreman walked out on the Low Sill

Structure for an inspection, and witnessed the collapse of a

67-foot-long wall along the south side of the intake channel, facing

the Mississippi.

The six Niagara Falls' worth of water pouring

through the channel pulverized the wall’s fragments and rammed them

through the structure. A giant whirlpool replaced the missing wall

and began attacking the structure, scouring away at the 90-foot deep

steel pilings that supported it. The foreman reported that you could

drive out onto the highway that crossed the structure, open your car

door, and the vibration from the water hammering through the

structure would close the door for you.

A

camera was lowered down a hole drilled down through the center of the

structure. The camera showed fish where there should have been solid

earth. The river had begun scouring out a football field-sized hole

over 50 feet deep underneath seven of the low sill's eleven gate

bays. The scour hole came within 150 feet of a second, even-larger

scour hole which had developed on the downstream side of the gates.

Had the two scour holes merged, the entire structure would have been

undermined and failed.

The

head of the Army Corps’ flood fight efforts, Major General Charles

C. Noble, gave the order to open the Morganza Floodway two days later

to relieve pressure on the Low Sill Structure. The governor of

Louisiana telephoned and asked if he had the authority to order that

the Morganza Floodway not be opened. General Noble told him no. When

complaints arose that he was not giving the promised five days'

notice, he replied that the river didn't give him five days' notice.

The

Corps brought in construction barges that continuously dumped

boulders into the scour holes to keep Low Sill Structure from

collapsing. In the end, the Low Sill Structure was saved but was

permanently damaged, and can now only handle 60% of the flow it once

could. So, the Corps was forced to build two new structures to

stabilize the situation: the Auxiliary Structure (cost: $480 million

2019 dollars) and the Sidney A. Murray Junior Hydroelectric Plant,

costing $1 billion (2019 dollars). We now have a much safer situation

than in 1973—but as we will see in Part II, ever-higher flood

crests are threatening to put an end to this reprieve.

Related works

Beyond

Control: The Mississippi River's New Channel to the Gulf of Mexico,

James Barnett Jr.’s detailed 2017 book.

John McPhee's 1987 essay, The Control of Nature.

Divine providence: the 2011 flood in the Mississippi River and Tributaries Project, by Army Corps historian Charles Camillo.

John McPhee's 1987 essay, The Control of Nature.

Divine providence: the 2011 flood in the Mississippi River and Tributaries Project, by Army Corps historian Charles Camillo.

https://www.wunderground.com/cat6/If-Old-River-Control-Structure-Fails-Catastrophe-Global-Impact?cm_ven=cat6-widget&fbclid=IwAR3rvZ827lPNI6sabkQxMl2RWGeLe6VRv0lZtAfHI1T-gS2X-yGO1OlNShc

Finally, here is the latest report from Oroville

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.