Summer

El Nino on The Way; Long Range Models Are Still Freaking Out

15

May, 2015

Well,

it’s official. According

to NOAA’s May 14 update,

we are now looking at a 90 percent chance that El Nino conditions

prevail through Northern Hemisphere Summer and a greater than 80

percent chance El Nino will last throughout all of 2015:

(Climate

Prediction Center’s ENSO probability forecast shows 90 percent

chance of El Nino through June, July and August and a greater than 80

percent chance that El Nino continues on through to the end of this

year. Image source: CPC/IRI.)

What

this means, especially when we add in likely record warm global

atmospheric temperatures (due to an excessive burning of fossil fuels

by human beings) throughout the El Nino event period, is some rather

odd, and probably extreme summer weather.

For

the US, it means an increasing likelihood of heavy precipitation

events from the southern plains states through the desert southwest.

Storm track intensification through the Pacific to North America

means that extreme rainfall events are a distinct possibility for

states like Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado, Arizona, Nevada, and New

Mexico. California may even see some abnormal summer rainfall, taking

a bit of the edge off the current drought.

Moving

southward, we find drier conditions for equatorial South America and

warmer than normal conditions for much of Brazil and Chile. Northern

Hemisphere Summer El Nino also enhances the risk of drought

throughout Australia, Southeast Asia, and India. In particular, India

is vulnerable to monsoonal disruption due to emergence of El Nino

during summer time. Enhanced precipitation near the date line also

can spur increased cyclone development for the Western Pacific.

(A

geographic representation of major prevailing summer El Nino

teleconnections. Image source: Berkley.)

These

sets of atmospheric changes are what we could generally expect from a

typical El Nino emerging throughout Northern Hemisphere summer. But

we’re not really dealing with normal conditions. We’re dealing

with global temperatures in the range of +0.8 degrees C above 20th

Century averages and + 1 C above 1880s averages. As such, we should

probably look to the margins for potential added impact.

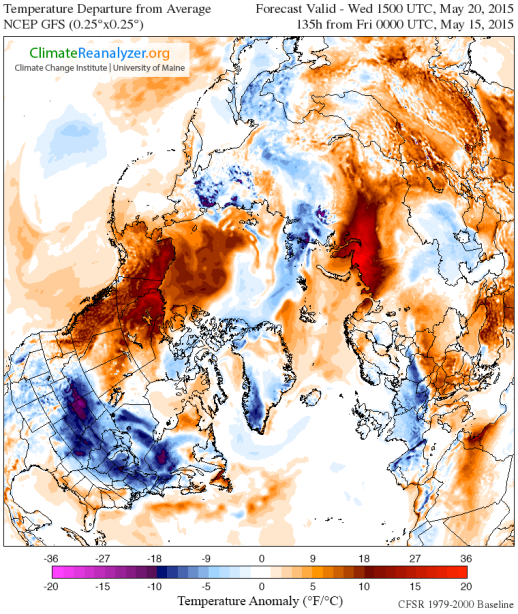

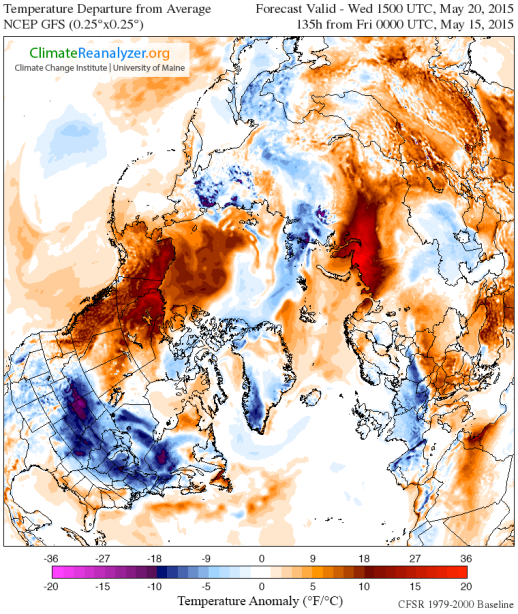

Two

areas in particular come to mind when considering such outliers. The

first region is a zone from Ukraine through to Western Russia. Under

added human heat forcing and conditions prevalent during summer El

Ninos, this region shows an increased likelihood of drought and

heatwave. A vulnerability that became particularly apparent during

the El Nino of 2009-2010. Drought conditions are somewhat widespread

for that region already this year. In addition, atmospheric high

pressure development in this vulnerable area would now, with the

enhanced surface warming due to human heat forcing, telegraph into

the Arctic through a vulnerable zone near Yamal and the Kara and

Laptev Seas. This would particularly enhance snow melt, permafrost

thaw, and sea ice melt throughout this region. So with El Nino now a

summertime certainty, this broader area certainly bears watching.

(El

Nino teleconnection to warming in Northwestern North America through

to the Arctic Ocean and in regions of Central, Western and Northern

Asia are possible this summer. Above is a GFS model forecast

temperature anomaly summary provided by The University of

Maine’s Climate

Reanalyzer.)

The

second region to look out for is the zone ranging from Northwest

Canada through Alaska and on into the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas.

Summer El Ninos tend to enhance warming for this region. When adding

in an already persistent heating throughout 2015 winter and spring,

the area will fall under greatly heightened risk of severe wildfires

and extreme and early snow and sea ice melt. Early extreme wildfires

in British Columbia combined with rapid sea ice recession already

ongoing through the Beaufort and Chukchi may well be indications that

such a trend has already asserted.

Some

Long Range Models Are Still Freaking Out Over a Potential Monster El

Nino Later This Year

Moving

beyond summer, we find a wide range of model consensus estimates

showing strong El Nino by fall and winter of this year. NINO 3.4

departures from an average of global model ensembles compiled

by Weather Underground hit

a value of +1.7 C by September. A level just below the so-called

Super El Nino Threshold of +1.8 C.

NOAA

CFSv2 ensembles have continued to ramp higher. Weighted seasonal

means have now spiked to +2.75 C for the key NINO 3.4 region with

unweighted ensembles hitting +3 C for October, November and December.

Weighted monthly means have spiked to +3 C anomaly for November while

unweighted anomaly values for the same month have proceeded off the

charts to an implied +3.5 C:

(Some

El Nino forecast models, like the one above, are really freaking out

about the potential for a monster event by the end of this year. This

NOAA model is basically off the charts. Image source: NOAA’s

Climate Prediction Center.)

Should

these predicted values emerge, they will literally blow the 1998-1999

Super El Nino out of the water. A monster event to shatter all

records.

It’s

likely that the currently extreme subsurface temperatures due to a

very strong warm Kelvin Wave as well as continued powerful west wind

back-bursts have kicked these models into freak out mode. And it’s

certainly an issue worth keeping an eye on.

But

it’s also worthwhile to consider that global deep ocean and

atmospheric dynamics will push to cool equatorial Pacific waters

during September, which would tend to tamp down warming extremes. A

factor that many models, which measure the shallow water zone

primarily, tend to miss.

“What

happens after this Kelvin wave response is all over the place. This

El Niño is being fought by the annual cycle, which tries to make

SSTs cold by Sept-Oct. That tendency keeps the warmest waters

back near the International Date Line and cuts off the Bjerknes

feedback. If the SSTs develop to be big enough to overcome the

annual cycle tendencies, then the Bjerknes feedback can kick in.”

For

reference, Bjerknes feedback involves storm formation and subsequent

west wind backbursts east of the Date Line and on toward South

America. A feedback that tends to trap and channel ocean surface heat

into the relevant El Nino zones and generally enhance warm sea

surface temperature anomalies:

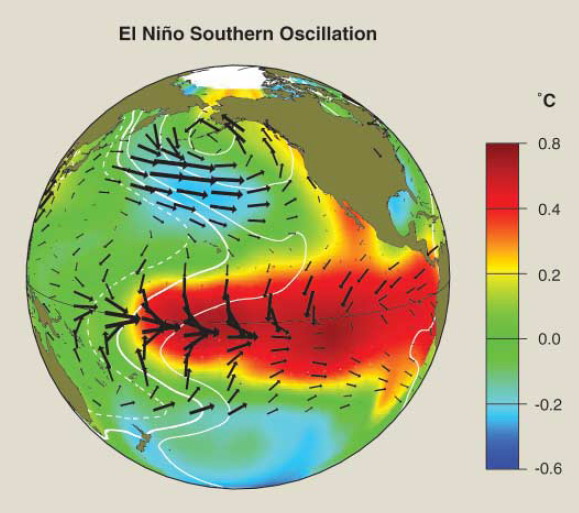

(Graphic

illustration of Bjerknes feedback showing sea surface temperature

anomalies in the color measure and direction of wind flow indicated

by black lines. It’s feature influenced by a general shoving of the

Walker Cell eastward [implied but not shown]. Image source: ENSO

as an Integrating Concept of Earth Science.)

So,

at this point, we have a lock on a weak to moderate El Nino event

continuing through this summer. After that time, an unprecedentedly

warm Kelvin Wave will do battle with a seasonal tendency for cooling

in the Eastern Equatorial Pacific. And if it wins out, we may see

something never before recorded in the whole of the Earth Sciences —

which would be very bad news for rates of global surface temperature

increase this year, along with a huge number of other issues.

If

not, we likely have a mid ocean El Nino through Fall and Autumn. And

that may be bad news for a California desperately in need of drought

relief.

Links:

A

Rare Mid-Year El Niño Event Is Strengthening

By:

Bob Henson

14

May, 2015

The

robust El Niño event anticipated for more than a year is finally

coming to fruition, according to the latest observations and

forecasts. NOAA's latest monthly

analysis,

issued on Thursday morning, continues the El Niño Advisory already

in effect and calls for a 90% chance of El Niño conditions

persisting through the summer, with a greater-than-80% chance they

will continue through the end of 2015. These are the highest

probabilities yet for the current event, and a sign of increased

forecaster confidence--despite the fact that we're in northern

spring, the very time when El Niño outlooks are most uncertain.

Figure

1. A schematic showing the processes involved in El Niño. The trade

winds shown by the arrow are weaker at this point than during La Niña

or neutral conditions; at certain times and at some locations, they

may even reverse, blowing from west to east. For a full explanation

of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, including additional graphics,

see the website published by the Australian

Bureau of Meteorology.

Image credit: BOM.

Forecasters

and computer models alike have been confounded by this event. In a

classic El Niño, the ocean and atmosphere are synchronized in a

mutually reinforcing pattern that pushes warm sea-surface

temperatures (SSTs) and thunderstorm activity along the equator

eastward for thousands of miles, from Indonesia toward South America

(see Figure 1). Sometimes the atmosphere doesn't respond to a "kick"

from the ocean, and an embryonic El Niño fails to develop. This was

the case last spring, when a powerful oceanic Kelvin wave (a broad,

shallow, slow-moving impulse) pushed warm water east across the

Pacific tropics. Keying off this wave, many of the global models used

in El Niño prediction called for a moderate or even strong El Niño

by the fall of 2014. However, the normal east-to-west trade winds

never reversed, which helped torpedo the needed ocean-atmosphere

synchrony. The ocean tried again last fall with another Kelvin wave,

but again the atmosphere failed to respond, and the SST warming

disappeared after a few weeks.

Figure

2. Recent weekly departures from normal across the four tropical

Pacific regions (top map) that are regularly monitored for signs of

El Niño and La Niña. Image credit: NOAA

Climate Prediction Center.

This

time, things appear to be different: SSTs have warmed for the last

several months, and more recently, trade winds have weakened. As of

Monday, the weekly-averaged SSTs over the four regions monitored for

El Niño were all at least 1.0°C above average (see Figure 2,

right). If the values

for all four regions

can sustain this feat throughout the next month, it'll be the first

time this has happened since November 1997, during the strongest El

Niño event of the 20th century. Just as significant, the

persistently warmer-than-normal SSTs over the western tropical

Pacific have now cooled, which helps support the reversal of trade

winds so critical to El Niño. The current SST map now resembles a

more textbook-like El Niño signature (see Figure 3, below), and

there is every indication that the ocean-atmosphere coupling will now

continue to grow.

An

event out of season

As

far as the eastern tropical Pacific goes, it's beginning to look a

lot like Christmas. El Niño--"the Christ child" in

Spanish--gets its name from its tendency to bring above-average SSTs

to the coasts of Peru and Ecuador around Christmastime. The

climatology of the eastern Pacific tends to support El Niño and La

Niña development during the northern autumn, maximum strength in the

winter, and decay in the spring. The current event is thus bucking

climatology as it continues into northern spring. The three-month

departure from average in the Niño3.4 region reached the El Niño

threshold of +0.5°C in Oct-Nov-Jan 2014-15, and it's hovered in the

weak range (+0.5 to +1.0°C] ever since, with a value of +0.6°C for

Feb-Mar-Apr 2015. Only 12 of the 65 prior years in the historical

database of El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events

have seen a value of at least +0.5°C during the Feb-Mar-Apr period.

Water temperatures in the Niño3.4 region are normally

at their warmest in May,

so the current warm anomaly is leading to especially toasty SSTs of

around 29°C (84°F). If this El Niño event does intensify, as

models strongly suggest it will (see below), it'll be one for the

record books. There are no analogs in the database for a weak event

in northern winter that becomes a stronger event by summer.

Persisting into northern fall will also greatly raise the odds of

this becoming a rare two-year event. In every case since

at least 1950

when El Niño conditions were present by Jul-Aug-Sep, the event

continued into the start of the next calendar year. Two-year El Niños

are more unusual than two-year La Niñas, but they do happen, as in

1968-1970 and 1986-1988. See the new

climate.gov blog

by Emily Becker for more on the unusual timing of this event.

Figure

3. Departures from normal for sea-surface temperatures as measured on

May 13, 2015. The warmer-than-average belt across the central and

eastern tropical Pacific is characteristic of El Niño. Image credit:

tropicaltidbits.com.

Northern

spring is an especially difficult time to predict El Niño evolution.

Computer-model skill at predicting ENSO is at its lowest then, in

part because of reduced east-west gradients in SSTs across the

tropical Pacific, but also due to factors that have yet to be fully

understood. "The Spring Barrier is the climate forecaster’s

equivalent of mayhem," says Michelle L'Heureux in an excellent

climate.gov discussion

of what forecasters often call the "spring predictability

barrier." Skill does begin to improve for forecasts produced in

May, according to L'Heureux, so we can begin placing more trust in

the 2015-16 El Niño predictions from this point onward--although

L'Heureux notes that even model runs produced in August still miss

about a quarter of the winter variability in ENSO.

How

strong will it get?

This

week's Niño3.4 SST anomaly of +1.0°C is at the threshold of a

moderate-strength event. Another 0.5°C would push the event into the

strong range, which was last observed in late 2009 and early 2010.

Klaus Wolter (NOAA Earth Systems Laboratory) has devised a

Multivariate

ENSO Index

(MEI) that uses multiple indicators to diagnose El Niño and La Niña.

Last year's event briefly nudged into Wolter's "strong"

category (defined as the top 10% of events) before subsiding. The MEI

is now again at the threshold of "strong," and a

statistical model recently run by Wolter finds a 44% chance that

strong conditions will be in place during Aug-Sep 2015, the time of

year when this statistical model is most accurate. "We have had

some pretty unusual (non-persistent) behavior of the ENSO-system in

the last four years that was anticipated better than by flipping a

coin, especially last year, but certainly not perfectly," said

Wolter in an email update.

Figure

4. Projected values of the Niño3.4 departure from average by

September, based on ensemble averages from a variety of global

ocean-atmosphere models (listed along left-hand side). The La Niña

and El Niño thresholds indicated by the shading on this graphic are

0.8°C, the values used in Australia. The comparable threshold used

by NOAA is 0.5°C, because U.S. impacts can occur with smaller

departures from average. Image credit: Australia

Bureau of Meteorology.

The

dynamical models run at various centers around the world to predict

ENSO are now unanimous in keeping El Niño going into northern

autumn. The values shown in Figure 4 (above) are ensemble averages

for each model, which means they smooth out the range of outcomes

depicted by multiple runs of the same model. (Each run has slight

differences in its starting point, to account for features too small

to be observed and the natural variations that result). Within each

ensemble, there's a wide range of outcomes projected by autumn 2015,

from a borderline El Niño to much more extreme values. Figure 5

(below) includes both the ensemble average and the individual members

for the seven models in the North

American Multi-Model Ensemble.

A number of individual model runs push the Niño3.4 index well above

+2.5°C over the next few months, and the entire NMME average is

around +2.2°C for November and December. By comparison, the highest

three-month departure observed in the entire 65-year NOAA database is

+2.4°C (Nov-Dec-Jan 1997-98).

Now

is a very good time to keep in mind that global models tend to

hyperventilate a bit when it comes to strong ENSO events. "This

is because the El Niño events are too shallow in the models,"

says Kevin Trenberth (National Center for Atmospheric Research).

"They don't have as much ocean heat content engaged, so there is

more of a surface signal." As for the stark variation among

individual model runs, it may be due to the spring predictability

barrier, as well as the result of another very powerful Kelvin wave

and a strong westerly wind burst now traversing the Pacific. Models

can easily predict a strengthening of El Niño conditions over the

next several months as these features continue eastward, but it's

tougher for the models to discern exactly what will happen after the

Kelvin wave reaches South America. Trenberth points to the

ocean-atmosphere coupling known as the Bjerknes feedback mechanism:

"What happens after this Kelvin wave response is all over the

place. This El Niño is being fought by the annual cycle, which tries

to make SSTs cold by Sept-Oct. That tendency keeps the warmest

waters back near the International Date Line and cuts off the

Bjerknes feedback. If the SSTs develop to be big enough to

overcome the annual cycle tendencies, then the Bjerknes feedback can

kick in."

Figure

5. Projected evolution of Niño3.4 temperatures from members of the

North American Mutli-Model Ensemble (members listed at top left).

Dashed lines denote individual model runs; solid lines denote

ensemble averages for each model. Image credit: NOAA

Climate Prediction Center.

What

can we expect this summer?

Because

it's quite rare to have intensifying El Niño conditions at this time

of year, it's difficult to glean a confident signal from past events

on how El Niño might affect U.S. summer weather. The global effects

of El Niño arise from a shifting of showers and thunderstorms into

the central and eastern tropical Pacific, which causes a

reverberating sequence of atmospheric waves that tend to enhance

precipitation in some areas and reduce it in others. In midlatitudes,

these relationships, called teleconnections, are usually strongest in

the winter hemisphere; for example, Australia often falls into

drought when El Niño is developing in Jun-Jul-Aug (see Figure 6). If

a strong El Niño does develop and persists into northern winter, the

likely U.S. impacts would be more clear-cut, including

wetter-than-average conditions across the southern half of the

country, from California through Texas to Florida. This month could

be seen as a sneak preview of sorts, with soggy conditions prevalent

across the central and southern Plains and two unusually-wet-for-May

systems reaching southern California, one last weekend and another

now on its way. There is some hope for drought relief in the Golden

State, given that the odds of an wetter-than-normal California rise

sharply for the strongest El Niño events, but by no means would a

wet winter be guaranteed. The strong El Niño of 1987-88 (which

happened to be the second year of a two-year event) produced a

drier-than-average winter from California to Washington.

Busy

day on the blog!

Bob

Henson

Figure

6. Global ENSO teleconnections (seasonal tendencies linked to El Niño

and La Niña) for northern summer (June - August). Image credit:

NOAA.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.