Firstly, what is happening right now, real time.

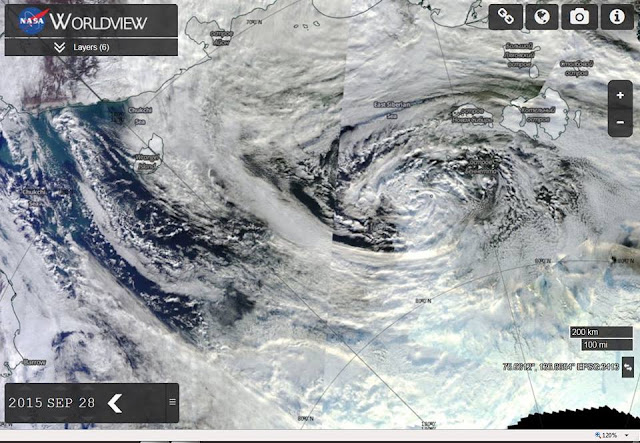

East Siberian Sea Storm 09 28 2015.

East Siberian Sea Storm 09 28 2015.

There

are about 5 to 6 billion tons of methane in the atmosphere now. Dr.

Malcolm Light calculates that about 25 billion tons of methane in the

atmosphere could raise the global average temperature 5 degrees C.

Dr. Natalia Shakova from the International Arctic Research Center

estimates that 50 billion tons of free methane is available to come

up at any time in the East Siberian Ocean. Storms churning up the

water in the East Siberian Ocean make me very concerned.

---Harold Hensel

And the latest research.

This can bring warm water both up to the surface and it can also bring warm water down to the seabed. Additionally, there are further feedbacks and there can be interaction between feedbacks, all of which can make things worse. An example is feedback#3, there is a danger that, as the sea ice declines, currents are weakened that currently cool the bottom of the sea, where huge amounts of methane can be present in the form of free gas or hydrates in sediments. The big danger is that warm water will melt ice in cracks in sediments and conduits that lead to hydrates. All this has been described for years at the Arctic-news Blog, e.g. in posts such as at http://arctic-news.blogspot.com/.../arctic-sea-ice-loss...

Comment

from Sam Carana

The

article says that "scientists are worried that this warm, salty

puddle might get stirred upwards". More worying is that it could

reach sediments at the Arctic Ocean seafloor. For many years, there

have been warnings that more open water enables stronger winds,

resulting in more mixing of the vertical water column. See feedback#4

at the feedbacks page

at http://arctic-news.blogspot.com/p/feedbacks.html

This can bring warm water both up to the surface and it can also bring warm water down to the seabed. Additionally, there are further feedbacks and there can be interaction between feedbacks, all of which can make things worse. An example is feedback#3, there is a danger that, as the sea ice declines, currents are weakened that currently cool the bottom of the sea, where huge amounts of methane can be present in the form of free gas or hydrates in sediments. The big danger is that warm water will melt ice in cracks in sediments and conduits that lead to hydrates. All this has been described for years at the Arctic-news Blog, e.g. in posts such as at http://arctic-news.blogspot.com/.../arctic-sea-ice-loss...

Voyage

traces stirred-up Arctic heat

Oceanographers have gathered fresh evidence that turbulence in the Arctic Ocean, driven by the wind, is stirring up heat from the depths

28 September, 2015

As

dwindling ice exposes more water to the wind, this turbulence could

close a vicious circle, accelerating the melt.

The

research team has measured heat rising from below that matches what

is arriving from the autumn sun.

They

spoke to the BBC by satellite phone as their month-long voyage headed

back into port.

Although

their findings are preliminary, the "ArcticMix" team has

been taken aback by what they've seen in the raw data.

"The

strength of heat coming up from below the surface has been as strong

as the heat coming down from the Sun," said the mission's chief

scientist, Jennifer MacKinnon, of the Scripps Institution of

Oceanography at the University of California San Diego.

"Admittedly,

the days are getting short here, and so the sunlight is not

incredibly strong at this latitude. But still, that very rarely

happens; that's kind of blown us all away."

The

source of that deep heat is a layer of warm water that is saltier -

and therefore denser - than water at the surface.

The

source of that deep heat is a layer of warm water that is saltier -

and therefore denser - than water at the surface.

"There's

a reservoir of heat in the Arctic Ocean, well beneath the surface,

that historically - when there's been a lot of ice - has been fairly

quiescent," Dr MacKinnon explained. "It's just been sitting

as a warm, salty puddle beneath the surface."

Now

that shrinking sea ice is exposing more water to the air, scientists

are worried that this warm, salty puddle might get stirred upwards.

And,

indeed, Dr MacKinnon's team has detected heat being brought to the

surface by surprisingly strong eddies - which they studied in detail

using a gadget that looks like "a torpedo with a record-player

needle at the front".

Matthew

Alford, the project's chief investigator, explained how this

"microstructure profiler" - developed in the University of

Washington's Applied Physics Laboratory - works when it is dropped

into the sea.

"When

it encounters very, very small currents of turbulence, the needle

just gets deflected slightly - exactly as it would if it was

travelling over a record," said Dr Alford, also from the Scripps

Institution.

"[These

tools] are allowing us to get a clearer view of not only the 3D

structure of these eddies, but also really directly measuring the

heat flux out of the top of these eddies, and into the bottom of the

ice."

Some

of these currents were bringing water as warm as 6C to depths

shallower than 50m; these are even more dramatic disturbances than

the team had expected.

"The

strength of [these currents] has been incredible," Dr MacKinnon

said. "We now need to disentangle what the contribution of that

process is to the multi-year, inexorable decline of the sea ice."

The

expedition reached its conclusion on Saturday, when the US National

Science Foundation's research vessel the Sikuliaq returned to port in

Alaska.

Among

the team's other toys were a "Swims" (shallow water

integrated mapping system) which could be trailed behind the boat to

take continuous measurements of temperature, depth and conductivity,

and a "bow chain" to probe the water in front of the boat.

"We're

interested in the structures of the ocean, not in the ocean after we

just rammed through it with a huge 261ft (80m) ship," explained

Dr Alford. "So the idea is to dangle sensors in front of it, and

have them sample the unperturbed ocean. That's been showing us some

very nice structures in the upper 20m or so of the ocean."

They

also deployed a stationary mooring: a heavy weight chained to a

float, with an automated profiler that crawled up and down the chain

collecting data until the team came back to pick it up.

"It

was exactly where we left it, which was amazing," Dr Alford

said. "Sometimes these things go drifting or get dragged by

fishing boats… This was a very boring recovery of our mooring and

that's the way we like it."

The

researchers encountered walruses, puffins and a lone polar bear

during their weeks at sea. Dr MacKinnon said the wildlife count was

lower than usual. "It's actually been super-quiet up here."

Quiet

- but fierce. "It's been chilly. There's been a number of nights

when people have been out working on deck, when it's snowing, it's

windy, and it's maybe -5C on board."

Dr

Julienne Stroeve, an arctic expert at the US National Snow and Ice

Data Centre, said the new results were valuable and interesting.

"I

think it is quite important to understand this type of mixing of

warmer ocean waters at depth with the sea ice," she told the

BBC.

It

will be crucial, Dr Stroeve added, to quantify exactly how much heat

is reaching the ice and how much melting it has caused.

"In

2007 more than 3m of bottom melt was recorded by [an] ice mass

balance buoy in the region, which was primarily attributed to earlier

development of open water that allowed for warming of the ocean mixed

layer. But perhaps some of this is also a result of ocean mixing."

Read more about the ArcticMix voyage HERE

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.