The problem is the same in New Zealand. The sole difference is that no one here will acknowledge it, still less write about it.

***

A

comment from Godlike Productions

“To all

the stupid people that think the US is a net exporter of oil please

read

The

US is the largest producer, but your reserves are not really that

impressive. The US still Imports over 7 million barrels a day. You

are not a net exporter and you only export your shale oil because you

do not have one processing facility that can frack light crude. Do

you have any idea what will happen to your economy in 5 days if Iran

point half their missiles at Qutar, Saudi Arabia and UAE oil

facilities?

Iran

has the ability to destroy your way of life for a long time, so

before you beat your war drums once again, you better understand the

pain you will feel because this time it will be very different. If

you really understand prophecy Babylon (they will get drunk on her

wine) is in actual fact Saudi Arabia and not the USA. Oils the wine

you are drinking, so stop puffing up your chests.

Great

pain and suffering is coming your way.”

Attack on Saudi oil facility could cause nightmare situation for Australia

For decades federal politicians have ignored appeals to preserve Australia’s strategic oil reserve. Now we have just three weeks of fuel in the tank.

16

September, 2019

Australia’s

worst nightmare is unfolding in the Middle East. Decades of neglect

have left us with just three weeks of fuel in the tank. Now, with

attacks on Saudi oil production, rationing is a genuine threat.

Last

month, the International Crisis Group issued a stark warning: “A

single attack by rocket, drone or limpet mine could set off a

military escalation between the US and Iran … that could prove

impossible to contain.”

This

weekend, just such an attack took place.

Both

the White House and Riyadh are refusing to rule out retaliation.

It’s

a scenario that leaves Australia out on a limb.

Despite

repeated warnings, successive governments have ignored international

commitments to maintain a strategic stockpile of oil. Such reserves

were designed to help see the country through an economic hiccup, an

international incident or severe natural disaster.

Now,

we’re facing just such a crisis.

Just

one missile attack has choked up to 7 per cent of the world’s oil

production. And analysts are already talking of price-spikes of up to

$US10 per barrel.

While

Saudi Arabia believes it can get one-third of lost production back

online this week, the threat to supplies seems suddenly very real.

What

if an all-out shooting war erupts?

ENERGY SECURITY

Australia’s

federal politicians are quick to cry “energy security” when it

comes to base-load electricity and coal-fired power plants. But in

regards to maintaining a sensible strategic fuel-oil reserve, not so

much.

In

recent decades, the nation’s neglected oil refineries have been

closed and tank farms sold off. In their place rise real estate

developments and light industrial parks.

Everything

seems fine, so long as the stream of supertankers keeps flowing into

our ports.

But

a flaring of tensions between the US and Iran earlier this year put

that into doubt.

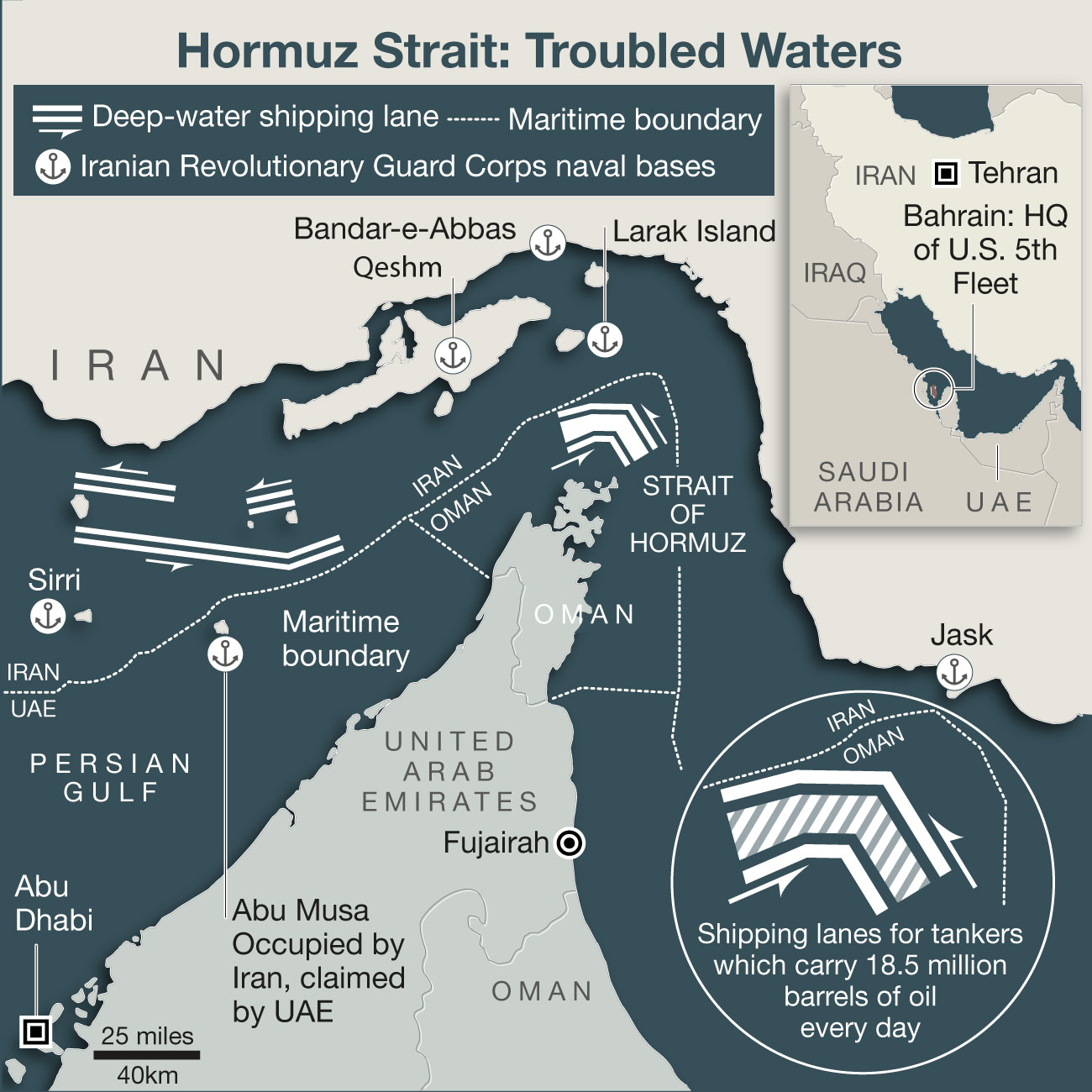

“Fifteen

to 16 per cent of crude oil and 25 to 30 per cent of refined oil

destined for Australia transits through the Strait of Hormuz. So it’s

a potential threat to our economy,” Prime Minister Scott Morrison

admitted last month.

Defence Minister Reynolds followed up by declaring: “So we’re doing everything that we can to be a good government and to be prudent, to make sure that we get a continuity of supply.”

And

that meant approaching the United States, cap in hand.

“We’ve

decided to begin negotiations with the United States to ensure that

we have a strategic reserve in place for circumstances that could

emerge, for scenarios that are unfavourable to Australia. This is a

sensible, low-cost way of going about this,” Mr Taylor said.

So,

in return for promises for a share of the US strategic crude hoard,

if the need arises, Australia committed a naval frigate and a

surveillance aircraft to the Persian Gulf.

That

crude will not be kept on Australian soil. Its supply relies on the

availability of commercial tankers to ship it here, as Australia has

long since sold off all of its own. And it is dependent upon the

world of US President Donald Trump.

And his mood towards nations relying on the US for oil security has been … testy.

Australia’s supply of oil relies heavily on its relationship with the US. Picture: Mick Tsikas/AAPSource:AAP

“So

why are we protecting the shipping lanes for other countries (many

years) for zero compensation,” Mr Trump tweeted in June. “All of

these countries should be protecting their own ships on what has

always been … a dangerous journey. We don’t even need to be there

in that the US has just become (by far) the largest producer of

Energy anywhere in the world!”

Now,

Australia is facing the most significant disruption in oil flows

since the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq in 1990. Then, like now, some

four to five million barrels of oil per day was taken out of the

system.

Australian

Strategic Policy Institute analyst Dr Malcolm Davis warns: “The

reality is that we’re woefully underprepared for a disruption to

fuel supplies.”

CONFIDENCE

CRISIS

The

attack on Saudi Arabia’s vital oil infrastructure has turned off

the taps for about 5.7 million barrels worth of daily production.

That’s

about half the nation’s total production, or between 5 and 7 per

cent of worldwide output.

Saudi officials insist they can restore the flow of crude in coming days: but not through the damaged oil facilities. Instead, they’ll open up their inventories and ramp-up production elsewhere.

Satellite image shows thick black smoke rising from Saudi Aramco's Abqaiq oil processing facility in Buqyaq, Saudi Arabia. Picture: Planet Labs Inc via APSource:AP

But

Saudi Oil production company Aramco now says cruise missiles — not

drones — hit 15 structures at its Abqaiq and Khurais facilities.

Abqaiq

is the world’s biggest crude-stabilisation facility, refining some

seven million barrels a day. Khurais produces about 1.5 million

barrels of crude a day.

“It

is definitely worse than what we expected in the early hours after

the attack, but we are making sure that the market won’t experience

any shortages until we’re fully back online,” one Saudi official

told media.

But the unspoken fear remains: what of its other facilities, also likely well within reach of a missile attack?

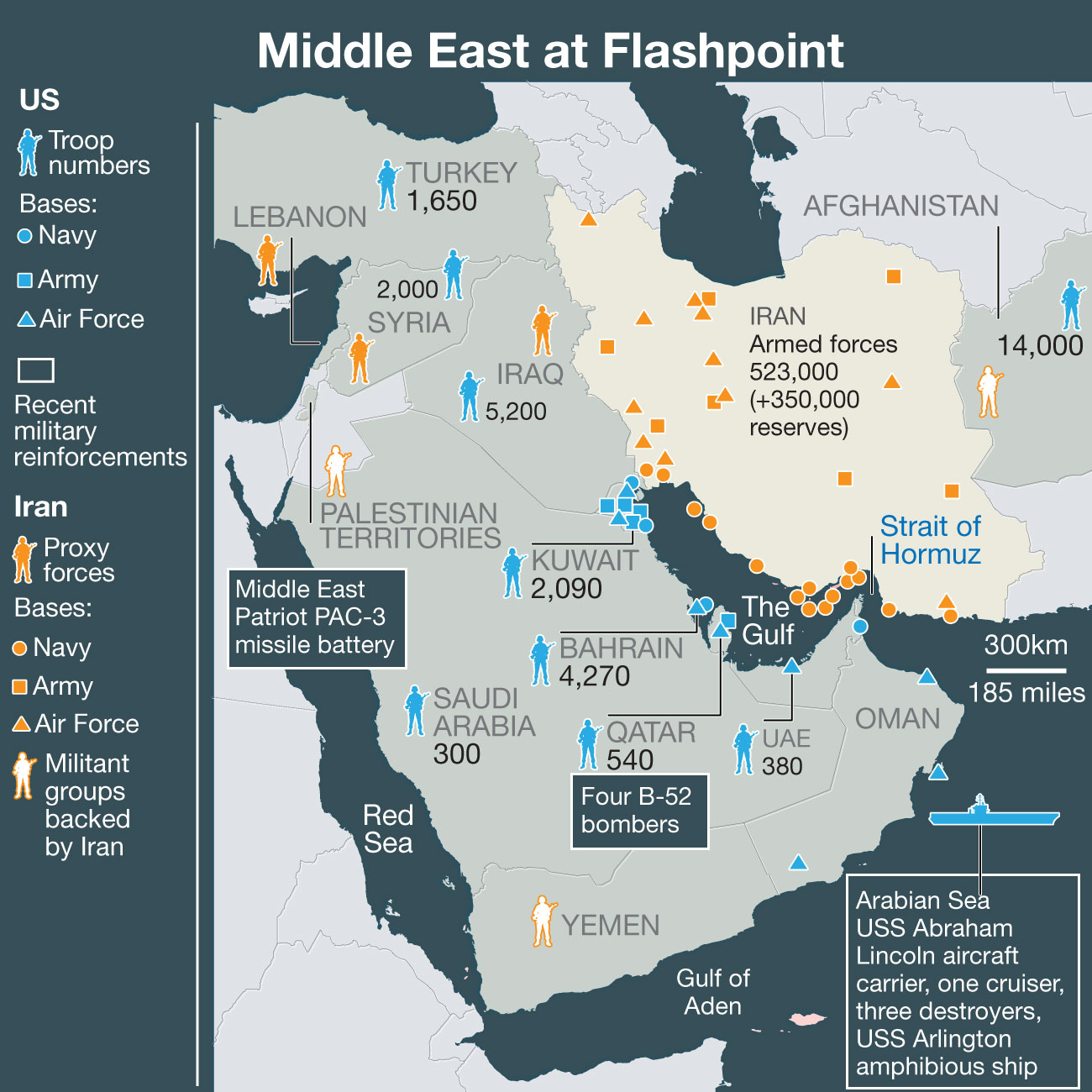

The

use of cruise missiles represents a significant escalation of

tensions in the Middle East, which has been seen a “proxy war”

between Iran, the US and Saudi Arabia being fought out in Syria, Iraq

and Yemen.

While

the antagonists have been reluctant to square-off face-to-face, that

may all be about to change.

The

International Energy Agency has issued a statement saying it was in

contact with Saudi authorities, primary producers and consumer

nations.

“For now, markets are well supplied with ample commercial

stocks,” the statement reads. “The IEA is monitoring the

situation in Saudi Arabia closely.”

RATIONING

GETS REAL

It’s

something not seen since the 1970s. But soon the prospect of

Australia’s petrol stations being locked up increases with every

new incident in the Persian Gulf.

Most

of Australia’s fuel comes from refineries in Japan and South Korea.

Both

those countries get most of their raw crude oil from the Middle East.

And analysts are saying Asian suppliers are likely to be the most

disrupted by the weekend attacks.

But

any pain Australia’s economy suffers — at least in the short term

— is of its own doing.

After

the establishment of the International Energy Agency following the

mid-1970s oil crisis, Australia signed a commitment to establish an

oil buffer. The goal was for member nations to have a reserve to buy

themselves time in the event of a crisis.

But

Australia has failed to meet that obligation for over a decade.

The

head of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute Peter Jennings told

ABC radio that the only way to provide a real buffer was to restore

our own onshore strategic oil reserves.

That

means more than just oil tanks. It also means rebuilding the nation’s

ability to refine that oil into usable products.

That

would cost billions.

“The

government doesn’t want to spend the money,” Mr Jennings says.

“But it’s now looking at a strategic situation where fuel

shortages could happen very quickly. And we’ve really got to find a

way to figure out a plan.”

And

he warns against relying upon the US being there for us in our hour

of need: “Look, it may help to mitigate the problem to some extent.

But, you know, in a crisis situation the Americans will — without

doubt — put their own priorities first.”

US

RELIANCE

The

United States is insulated from the international fallout of the

Saudi attacks through its own oil production industry and vast

strategic reserves.

Government

officials have already indicated they may release some of their

emergency stockpiles to prevent an economically damaging price spike.

It

all depends upon US President Donald Trump.

He

has the power to authorise an emergency release from its 650 million

barrels of stockpiled crude. These are held in heavily guarded

underground storage caverns in Texas and Louisiana.

It

represents about one month worth of US consumption.

But Energy Secretary Rick Perry “stands ready to deploy resources from the Strategic Petroleum Oil Reserves if necessary to offset any disruptions to oil markets as a result of this act of aggression,” a department statement reads.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.