Hang down your heads, Aussies and Kiwis in shame!

Australia, or at least the more intelligent parts of the population, seems to be undergoing a slow awakening to climate change and the destruction of its ecosystem just as we enter the runaway phase and it's too late.

The time to talk about this and take action was about 25 years ago.

There as everywhere the Powers-that-be seem to want to keep it all under wraps and have decided that now is the perfect time to sack hundreds of climate scientists and return to Year Zero.

There as everywhere the Powers-that-be seem to want to keep it all under wraps and have decided that now is the perfect time to sack hundreds of climate scientists and return to Year Zero.

Sydney

experiences highs of 28C when average temperature for May is 19.5C,

with warmer weather set to continue for at least a week in many parts

of country

18

May, 2016

Your

memory is not playing tricks on you – it has been unusually warm

across much of eastern Australia this May.

The

Bureau of Meteorology said temperatures had been “definitely well

above average” across most of the eastern states so far this month.

The

high for Sydney was 28C on Tuesday when the average temperature for

May is 19.5C.

Duty

forecaster Philip Landvogt said it was a similar story for “pretty

much all of the eastern states”.

“All

the way from Brisbane down to even Hobart is warmer than average for

this part of year.”

In

Brisbane the average high temperature for May is 23.2C – and so far

this month not a day has fell below 24C. The city can expect

temperatures in the mid-to-high 20s “well into next week”.

Canberra

has also been warmer than the average May, with an average high of

18.9C so far this month compared with the usual 15.6C.

And

the effect has been felt as far south as Melbourne, where this month

it has been 20.3C while the average May day peaks at 16. 7C.

The

cause was warm ocean temperatures off the east coast and over

northern Australia and prevailing winds bringing warm air from over

the central part of the country to the eastern states.

“The

combination of those two factors has been the reason we’ve had

these warm temperatures,” said Landvogt.

Landvogt

said the warmer weather was set to continue for at least a week in

many parts of Australia.

A

high of 25C for Sydney on Wednesday was forecast to be followed by at

least seven days of temperatures in the region of early to mid-20s –

all well above the May average of 19.5C.

Tasmania

and Melbourne would start to cool down early next week, with the

arrival of a cold front in the coming days.

The

warm water temperatures off the east coast of Australia and dry

conditions over much of the country that were associated with El Niño

were continuing but Landvogt said that system would start to break

down soon.

Sea

surface temperatures across the tropical Pacific Ocean have cooled in

the past fortnight as El Niño draws closer to an end.

Landvogt

said there was a “50-50 chance” of a La Niña weather pattern

forming with the onset of winter. That could lead to more rainfall

over the winter through northern, central and eastern Australia.

The

unseasonal weather follows confirmation of the hottest April on

record globally – and the seventh consecutive month to have broken

global temperature records.

The

latest figures, released by Nasa over the weekend, smashed the

previous record for April by the largest margin ever recorded,

setting 2016 up to be the hottest year ever.

The Sydney Morning Herald is also starting to talk about climate change about 30 years too late. The horse has bolted and it is pointless to to have discussions about closing the gate.

When

should we worry about climate change?

18

May, 2016

News that Tasmania's Cape Grim weather site had recorded its first baseline reading of 400 parts per million of carbon dioxide sparked some debate over the meaning of the milestone.

As we noted ahead of the declaration of the first recording of 400ppm in the southern hemisphere, the primary greenhouse gas increase carried not much more global warming significance than, say, 399 or 401 ppm.

But as with other markers - such as Australia's foreign debt passing a $1 trillion - the 400 ppm tally helps focus our attention.

Smoke rises from Canadian wildfires burning near Fort McMurray, Alberta as the fire season started a month early this year. Photo: Darryl Dyck, Bloombeg

"People react to these things when they see thresholds crossed," David Etheridge, a CSIRO principal research scientist, told us. Even more upbeat was Paul Fraser, the CSIRO scientist who had helped set up Cape Grim 40 years ago. He told 9news.com.au that passing the landmark would be a "psychological tipping point".

Other warning signs - such as the 1 degree warming point reached last year - did at least spur nations to agree at the Paris Climate Summit that temperature increases should be limited to 1.5-2 degrees, even if national policies made 3 degrees more likely.

And so, with CO2 concentrations marching past 400 ppm, when should we start worrying about global warming?

No sign of a cooling off in global temperatures. Photo: Peter Rae

"About 30 years ago," is the blunt answer from David Karoly, a climate scientist with Melbourne University. That's when CSIRO and other scientists declared we had a problem.

"But we shouldn't give up, either," he told me this week. "The worry - and the [climate] action - should now be increased."

During the three decades since, we have poured trillions of dollars into fossil fuel extraction, refining and consumption and a much smaller sum into renewable energy that will have to replace coal, oil and gas - and soon.

As much 60 per cent of the corals at the northern end of the Great Barrier Reef may have died in the current bleaching event. Photo: Eddie Jim

Yet clean energy technologies continue to make rapid advances, including the latest breakthrough at the University of NSW lifting solar efficiency levels to above 34 per cent.

Worries mount

When it comes to extreme weather, there's certainly been a lot to be concerned about in 2016.

Each of the last 12 months is now the hottest on record for that month, with April adding the recent string of beating-by-biggest-margin months.

(See NASA's chart showing temperatures were 1.11 degrees warmer than the 1951-80 average, with large areas in the north particularly warm, while Australia had its second-warmest April.)

Among the climate-related threats, Canada's forest fire season started about a month early. One huge blaze near Alberta's tar sands forced the evacuation of about 88,000 people from the city of Fort McMurray.

The monster El Nino, riding on top of about one degree of background warming, has triggered widespread bleaching of the corals around the world, including our cherished - but apparently expendable - Great Barrier Reef.

More than half the corals in the largely pristine northern end are now dying or dead the reef's Marine Park Authority chief Russell Reichelt told the Senate earlier this month.

On the plus side

However, a dose of of warming can be welcomed where it take off the chill - as in parts of the US - or in Sydney, where summer feels like never lost of its grip even with winter just weeks away.

And all that extra CO2 is leading to a "greening" of the planet with about one-quarter of humans' carbon emissions being taken up by plants, a recent Nature paper found.

But many other changes are far from benign - at least according to the preservation of many existing eco-systems.

Less glamorous than corals, the kelp forests off eastern Tasmania are being destroyed by warm water species swept south by the strengthening and warming East Australian Current. Similarly, the massive dieback of mangrove forest in the Gulf of Carpentaria apparently linked to extreme weather got scant national media coverage.

And, as for the high Arctic where the remarkably prolonged above-average temperatures have led to record-low levels of sea ice, changes are likely to be further from our daily minds.

But less sea ice means less light reflected back to space and more heat absorbed by the oceans - and so the cycle builds and so should our concern.

Spiral warning

In case you missed it, Ed Hawkins, a climate scientist at the UK's University of Reading, came up with the illustration below to help us appreciate the spiralling warming trend since the middle of the 19th century.

By that gauge, when the temperature increase breaks past the 1.5 degrees warming - perhaps in coming months before the El Nino in the Pacific fully stops giving back heat to the atmosphere - will be sufficiently concerned then to act?

Climate scientists, such as Professor Karoly, know globally warming limits agreed at international summits to prevent dangerous climate change - such as 1.5-2 degrees range agreed in Paris - are arbitrary in a similar way to 400 ppm.

"You'd be hard-pressed to find scientists agreeing that 1.5 degrees would be manageable for our reef," he said. "Look at what's happening to the reef this year - and that's with 1 degree warming."

Recent work by his team has identified that on current temperature and carbon emissions trends, the Great Barrier Reef will be hit by bleaching events every second year by 2035.

Other eco-systems, such as alpine ones, are also being affected as species shielded from predators by cool temperatures have literally nowhere to hide.

Big one to worry about

Natural fluctuations mean temperature spikes such as we have seen over the past year can recede - at least partly.

As this year's El Nino in the Pacific lurches towards becoming a La Nina - when equatorial winds turn back to be mostly west-ward blowing and strengthen - we can expect the run of record temperature reading to be broken.

However with greenhouse gas concentrations still rising, the heat we are trapping in the Earth's biosphere - the land, air and sea - will keep on increasing.

And for those climate sceptics who thought the first decade of the 21st century marked a slowdown in temperature increases - the so-called "warming hiatus" - their case for holding off carbon emission cuts is about to get harder to make.

As Fairfax Media noted back in late 2014, a long-lived climate phenomenon named the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, has begun to switch to its positive phase. In fact, climate experts have in the past few days detected it hitting a new high.

"You're playing catch up - now the natural factors want to make the planet warmer," David Jones, head of climate analysis with the Bureau of Meteorology, said.

"Historically when you've had a positive PDO, global temperatures are higher and the rate of warming tends to be quicker."

Some scientists view PDOs as a slower version on the El Nino pattern that forms in the Pacific every three to seven years. Others see it as a separate phenomenon.

"In reality, it's probably a bit of both," Dr Jones said.

Such a PDO switch - it is an 11-year rolling average - would indicate oceans will become less of a sink for the planet's surplus heat - and may even give more of it back to the atmosphere.

That means global conditions will favour more El Nino events but also when La Ninas come, they will tend to be more extreme.

In other words, we could soon have a lot more to worry about.

Back to Year Zero.

The response of my friend Kristy Lewis who is involved in climate research is:

"What southern hemisphere research? Doesn’t exist in cliamte change unless you can put a case forward that involves making money. Most climate reseachers in Australia have gone overseas. Those that are left are sunsisting in teaching positions."

Australian climate job cuts leave hole in Southern Hemisphere research

Details

of redundancies at CSIRO alarm global climate community.

Dani Lewis

18 May, 2016

Staff at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), which employs thousands of scientists across Australia, were told over the past week where long-awaited job cuts in climate science are likely to fail.

Many CSIRO researchers who spoke toNature about

the lay-offs requested anonymity so as not to breach the

organization's communications policy, which tells researchers not to

discuss funding or management decisions. But the information that is

trickling out means that scientists are already evaluating the likely

impact on research – although a consultation process means that it

may be months before an expected 140 lay-offs in climate research are

complete.

“It’s

significant beyond the numbers because of our overall uniqueness,”

says oceanographer Peter Craig, who worked for CSIRO for 30 years but

retired from the agency at the end of March. “The rest of the world

does rely on us for both measurements and interpretation of what’s

going on on this side of the world.”

Ice lab threatened

CSIRO

scientists in Melbourne who analyse ice cores from an ice cap called

Law Dome in Antarctica – a group colloquially known as the ‘Ice

Lab’ – fear their programme is one that might be curtailed.

Because

the Law Dome accumulates ice very rapidly and traps low levels of

impurities as it grows, its cores constitute the most reliable record

of greenhouse-gas emissions over the past 2,000 years, says Malte

Meinshausen, a climate modeller at the University of Melbourne and

the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany. Climate

models that predict how many degrees of warming will occur under

different greenhouse-gas emissions scenarios rely heavily on its

record, Meinshausen says.

David

Etheridge, head of ice core research, says that he has not been told

he will lose his job, but that other scientists who do ice core

analysis are facing redundancy. CSIRO has said that the Ice Lab will

remain open, but Etheridge believes that cuts will have negative

consequences for palaeo-climate research and the climate models that

rely on it.

Aerosol fear

CSIRO

researchers also fear that Australia’s contributions to the world’s

largest ground-based network of aerosol sensors, called AERONET — a

NASA-led project to verify the sometimes ambiguous aerosol

measurements made by satellite — are in jeopardy. On 1 May, Brent

Holben, who leads the AERONET project in Greenbelt, Maryland, wrote

to CSIRO to urge that it reconsider its cuts.

He said that they would

cause the loss of aerosol measurements over a large region of the

Southern Hemisphere.

Asked

for a statement, the agency said: “CSIRO is working with partners

to identify the most efficient way of delivering this work.”

Sea-level expertise

Notable

among individual staff set to lose their jobs is John Church, an

expert on sea-level rise who has worked for CSIRO for 38 years and

who coordinated a chapter on sea-level change for the most recent

assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

(IPCC), released in 2014.

Church

was at sea on the research vessel RV Investigator when

he learnt last week that, as he had expected, he would be made

redundant.

“John

has probably done more to lay a really firm scientific foundation

under the issue of sea-level rise than anyone else in the world,”

says Steve Rintoul, a fellow oceanographer at the CSIRO. “The

signal that this sends to both staff within and outside of CSIRO is

really horrible.”

The

RV Investigator’s

voyage from the Southern Ocean to the Equator is currently mapping

deep-ocean temperature and chemistry under the international GO-SHIP

program, and is also deploying Argo

and biogeochemistry floats that

gather data at the ocean surface. CSIRO says that neither the

frequency of the ship’s expeditions nor the associated data

analysis will be adversely affected. But researchers who did not want

to be named said that, with the cuts, they doubted that such

extensive surveys would be possible in the future, or that other

Australian agencies could fill the gaps in expertise if oceanography

groups were disbanded.

CSIRO.

CC-BY-3.0 Layoffs

in CSIRO's oceanography groups may dampen the productivity of the

Australian research vessel RV Investigator.

CSIRO

had first

announced in February that

it planned to shed hundreds of jobs as part of a strategic shift away

from basic climate science; in April, it confirmed that

this included almost 140 lay-offs in its ‘Oceans and Atmosphere’

and ‘Land and Water’ divisions.

The

CSIRO cuts are “inexplicable”, says Thomas Stocker at the

University of Berne, who co-chaired the IPCC’s Working Group I

(which examines the physical science of climate change) between 2008

and 2015. He is particularly concerned about the cuts to the

sea-level research group. “It’s simply not understandable for me

that the stewards of a country that is so fundamentally exposed to

sea-level rise is able to basically terminate research activity in

their own country,” he says.

Negotiations

since February have staved off cuts in some programmes, says one

senior scientist at CSIRO’s Aspendale site in Melbourne. For

example, CSIRO ratcheted back cuts for a team that analyses air

pollution from data drawn from the remote Cape Grim Observatory in

Tasmania, so that Australia could continue to meet obligations to

international agreements such as the Montreal Protocol, which

governments signed in 1987 to protect the stratospheric ozone layer

from damage by chlorofluorocarbons.

But

it seems that the bulk of the cuts will not be reversed. Although

more than 3,000 scientists have urged Australian politicians and

CSIRO management in an open letter to reconsider the proposed

lay-offs, the government has distanced itself, saying that they are

an agency-level decision. With national elections set for 2 July, the

opposing Labor party has said that if it were elected, it would

direct the CSIRO's board to stop the lay-offs. However, it would not

reappoint scientists who accept redundancies before then

Mangrove Ecosystems In Queensland Are Dying Just Like The Great Barrier Reef

17

May, 2016

Australia

is still recovering from the massive coral bleaching in the Great

Barrier Reef, however, its ecosystem gets another blow — the

Mangrove population in Queensland is dying.

Scientists

are yet to establish an explanation of what could have caused it, but

they are certain that the damage covers a large area.

The

hot climate coinciding with the dry period of Northern Australia

could have triggered the widespread deaths, because there is no other

major event, such as cyclone, tsunami or oil spill in the area that

could have resulted in such destruction of the mangrove ecosystem,

said Norm Duke, a professor from James Cook University and a

spokesman for the Australian Mangrove and Saltmarsh Network (AMSN).

Ecosystem

At Risk

Mangroves

are crucial because they minimize the erosion of shorelines and

prevent sediment from going offshore, thus, filtering the inland

water before it enters the sea. Without the mangroves, coastal

ecosystem like seagrass and corals could vanish as well.

These

mangroves also serve as fish sanctuaries. Fishermen have already

reported about meager catches along with the diminishing mangrove

ecosystem.

Because

of their extensive root network, mangroves can store and trap carbon

five times more than the normal forest. When they are lost, Duke

explained, the carbon would be released into the atmosphere and might

intensify global warming.

Close

Monitoring Needed

AMSN

officials cannot closely monitor such an expansive damaged area

because they do not have the funding to do so. They only rely on

information from the locals and imaging from Google Earth.

Australia

has 7 percent of the world's mangrove population, and Duke fears that

if the numbers continue to decline, the ecosystem will be

significantly disrupted.

"Once

the trees have died, they can only grow back from seedling which may

take 20 to 30 years before you get a functioning forest again,"

said Duke.

Initial

observations of the mangrove dieback were presented during the AMSN

Conference. Duke said that monitoring efforts should be carried out

to establish a baseline condition of the shorelines.

The

mangroves in the Indo-Pacific are also being threatened to become

extinct by 2070 because of rising sea levels.

While

scientists are still figuring out the exact cause of the mangrove

deaths, it seems that climate change could be the one to blame.

Just in case you have been way on Mars and weren't already aware of this....

A Death of Beauty — Climate Change is Bleaching the Great Barrier Reef Out of Existence

21

April, 2016

Extinction.

It’s

a hard, tough thing to consider. One of those possibilities people

justifiably do not want to talk about. This notion that a creature

we’re fond of and familiar with — a glorious living being along

with all its near and distant relatives — could be entirely removed

from the web of existence here on Earth.

Our

aversion to the topic likely stems from our own fear of death. Or

worse — the notion that the entire human race might eventually be

faced with such an end. But extinction is a threat that we’ll see

arising more and more as we force the world to rapidly warm. For

species of the world now face existential crisis with increasing

frequency as atmospheric and ocean temperatures have risen so fast

that a growing number of them have simply become unable to cope with

the heat.

The

Great Barrier Reef of Australia — the world’s largest single

structure made up of living organisms — is no exception. For this

1,440 mile long expanse of corals composed of more than 2,900

individual reefs that has existed in one form or another for

600,000 years has

suffered a severe blow —

one from which it may never be able to recover. One that appears

likely to kill up to 90 percent of its corals along previously

pristine regions in its northern half.

(Governments

failed to listen to the warnings of scientists like Terry Hughes.

Now, it appears that the Great Barrier Reef has been hit by a blow

from coral bleaching from which it may never be able to recover.

Video source: Australian

Broadcasting on the Great Barrier Reef’s Worst Coral Bleaching

Event on Record.)

The

damage comes in the form of extreme ocean heat. Heat resulting from

global temperatures that are now well in excess of 1 degree C above

preindustrial times. Heat that has forced ocean temperature

variability into a range that is now lethal for certain forms of sea

life. Particularly for the world’s corals which are now suffering

and dying through the worst global bleaching event ever experienced.

The

Worst Global Coral Bleaching Event Ever Experienced

During

2014 the oceans began to heat up into never-before seen temperature

ranges. This warming initiated a global coral bleaching event that

worsened throughout 2015. By early 2016 global surface temperatures

rocketed to about 1.5 C above 1880s averages for the months of

February and March. These new record high temperatures came on the

back of annual carbon emissions now in the range of 13 billion tons

each year and at the hotter end of the global natural variability

cycle called El Nino. Both the atmosphere near the land surface and

the upper levels of the ocean experienced this extreme warming.

In

the ocean, corals rely on symbiotic microbes to aid in the production

of energy for their cellular bodies. These microbes are what give the

corals their wild arrays of varied and brilliant colors. But if water

temperatures rise high enough, the symbiotic microbes that the corals

rely on begin to produce substances that are toxic to the corals. At

this point, the corals expel the microbes and lose their brilliant

coloration — reverting to a stark white.

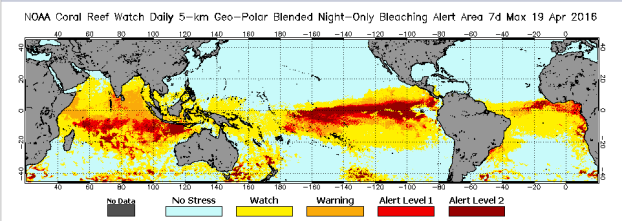

(A

vast region of the world’s ocean system continues to experience

coral bleaching. In area, extent, height of extreme temperature, and

duration, the current global coral bleaching event is the worst ever

experienced by a good margin. As global temperatures continue to warm

due to ongoing fossil fuel burning and related carbon emissions,

widespread coral bleaching is likely to become an annual occurrence.

Temperatures have risen far enough and will continue to rise for long

enough to set about ocean conditions that will result in mass coral

die-offs around the world. Image source: NOAA.)

Bleaching

isn’t necessarily lethal to corals. However, once the microbes are

gone, the corals have lost a key energy source and will eventually

die without them. If ocean temperatures return to normal soon enough,

the corals can begin to accept the symbiotic microbes back, return to

a healthy cellular energy production, and survive — albeit in a

weakened and more vulnerable state for some time to come. But if

ocean temperatures remain too warm for an extended period, then the

corals will be deprived of energy and nutrients for too long and they

will inevitably perish.

The

kind of coral bleaching event that we’re experiencing now is a mass

killer of corals. Not simply due to the heat itself, but due to the

long duration of the extreme temperature spike. By late February,

many ocean scientists were very concerned about the already severe

damage reports that were starting to come in. At

that time, NOAA issued this warning:

“We are currently experiencing the longest global coral bleaching event ever observed. We may be looking at a 2- to 2½-year-long event. Some areas have already seen bleaching two years in a row.”

93

Percent of Great Barrier Reef Affected by Bleaching

By

late February, the level of concern for the Great Barrier Reef was

palpable. Stark reports were starting to come in from places like

Fiji — which had experienced two years of severe bleaching — and

Christmas Atoll about 1,300 miles south of Hawaii — whose

reported losses were best described as staggering.

So far, the worst of the hot water had stayed away from Australia’s

great reef.

But

by early March a plume of very extreme ocean heat began to appear

over The Great Barrier Reef’s northern sections. Sea surface

temperatures spiked to well above, a dangerous to corals, 30 degrees

Celsius for days and weeks. This 30 C or greater heat extended deep —

hitting as far as 50 meters below the ocean surface over the reef.

And it rippled southward — hitting section after section until few

parts of the reef were spared.

Terry

Hughes, one of the world’s foremost experts on the Great Barrier

Reef, on

March 18th tweeted his fear and anguish over the situation:

At

this point, there was no stopping the tragedy. Fossil fuel emissions

had already warmed the airs and waters to levels deadly to the living

reef. It was all researchers could do to work frantically to assess

the damage. Teams of the world’s top reef scientists swept out —

performing an extensive survey of the losses. More than 911 reef

systems were assessed and, in total, the

teams found that fully 93 percent of the Great Barrier Reef system

had experienced some level of bleaching.

Final

Death Toll for Some Sections Likely to Exceed 90 Percent

In

extent, this was the worst bleaching event for the Great Barrier Reef

by a long shot. Back during the previous most severe bleaching events

of 1998 and 2002, 42

percent and 54 percent of the reef was affected.

By any measure, the greatly expanded 2016 damage was catastrophic.

“We’ve never seen anything like this scale of bleaching before.

In the northern Great Barrier Reef, it’s like 10 cyclones have come

ashore all at once,”said Professor

Terry Hughes in the ARC coral bleaching report.

Out

of all the reefs surveyed in the report, just 7% escaped bleaching.

Most of these reefs occupied the southern section — a region that

was spared the worst of the current bleaching event due to cooler

water upwelling provided by the powerful winds of Hurricane Winston.

But impacts to the Northern section of the reef could best be

described as stark. There,

a section composing almost the entire northern half of the reef saw

between 60 and 100% of corals experiencing severe bleaching.

In the reports, Hughes notes that many of these corals are not likely

to survive. In the hardest hit reefs — which were in the most

remote sections least affected by Australia’s industrial run-off —

algae has been observed growing over 50 percent of the corals

affected — an

indication that these corals are already dead:

“Tragically, this is the most remote part of the Reef, and its remoteness has protected it from most human pressures: but not climate change. North of Port Douglas, we’re already measuring an average of close to 50% mortality of bleached corals. At some reefs, the final death toll is likely to exceed 90%. When bleaching is this severe it affects almost all coral species, including old, slow-growing corals that once lost will take decades or longer to return (Emphasis added).”

But

with the oceans still warming, and with more and still worse coral

bleaching events almost certainly on the way, the question has to be

asked — will these corals ever be afforded the opportunity to

recover?

A

Context of Catastrophe with Worse Still to Come

As

ocean surface temperatures are now entering a range of 1 C or more

above 1880s levels, corals are expected to experience bleaching with

greater and greater frequency. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change in 2007 identified

the time-frame of 2012 to 2040 as a period of rising and extreme risk

to corals due to bleaching.

IPCC also identified bleaching as the greatest threat to corals and

related reef-dependent sea life.

When

ocean surface temperatures warm into a range of 2 C above 1880s

levels — the kind of severe global heating that could arise under

worst-case fossil fuel emissions and related warming scenarios by the

mid 2030s — corals in the Great Barrier Reef are expected to

experience bleaching on an annual basis. Every year, in other words,

would be a mass coral bleaching and die-off year.

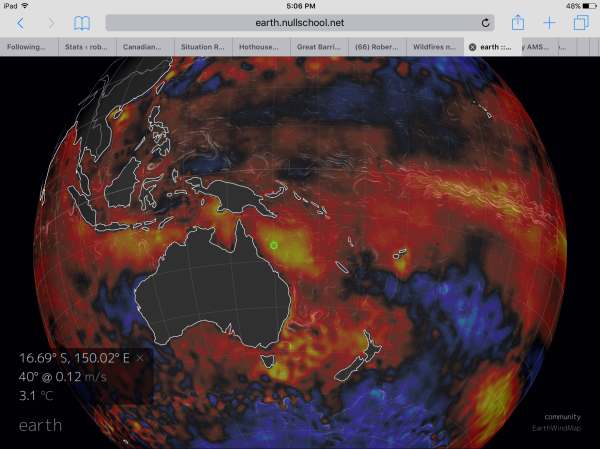

(Sea

surface temperatures and temperatures withing the top 50 meters of

water over the Great Barrier Reef of Australia rose to 3-4 C above

average during the austral Summer and Fall of 2016. These record

temperatures lasted for weeks in some regions setting off the worst

coral bleaching event the Great Barrier Reef has ever seen. By

mid-Century, coral bleaching and mass die-offs are likely to occur on

an annual basis as global temperatures surpass the 1.5 C and 2 C

thresholds. Image source: Earth

Nullschool.)

Globally,

bleaching events under even moderate fossil fuel emissions scenarios

would tend to take up much of the Equatorial region on an annual

basis by mid-Century. Events that can, during single years, wipe out

between 90 and 95 percent of corals at any given location. A handful

of corals will likely survive these events — representing a remote

and far-flung remnant who were simply a bit hardier, or lucky, or who

had developed an ability to accept microbes that are tolerant to

warmer temperatures. But these hardy or fortunate few would take

hundreds to thousands of years to re-establish previous coral reef

vitality even if other harmful ocean conditions did not arrive to

provide still more damage.

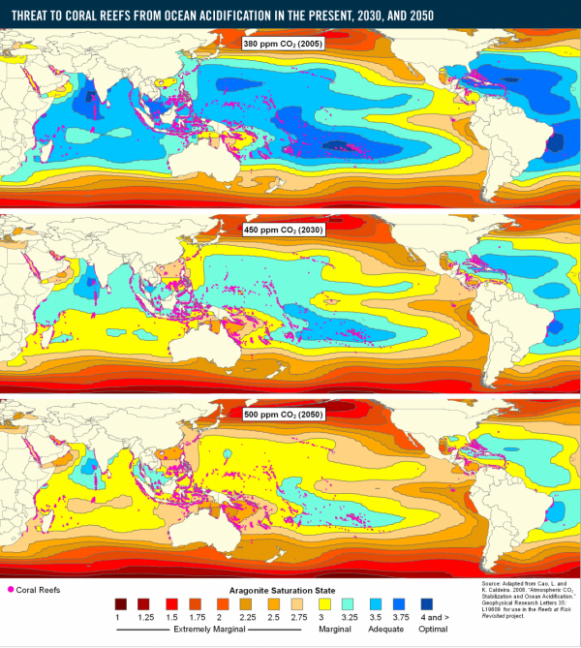

As

coral bleaching expands at the Equator due to increasing rates of

ocean warming, increasing levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere

causes oceans to become more acidic. Cooler waters at the poles are

better able to transfer gasses into the ocean’s waters. And higher

levels of carbon dioxide in the world ocean results in a growing

acidity that is harmful to corals. Increasing levels of ocean acidity

thus creep down from the poles at the same time that bleaching events

move up from the Equator.

If

fossil fuel emissions continue, by mid-Century atmospheric carbon

dioxide levels in the range of 450 to 500 parts per million will have

provided a never-before seen spike to ocean acidity. Such high ocean

acidity would then provide a second severe blow to corals already

devastated by bleaching events. It’s a 1-2 punch that represents a

mass extinction threat for corals this Century. And we’re starting

to see the severe impacts ramp up now.

(Coral

bleaching is a severe threat to tropical coral reefs now. But CO2

potentially hitting above 500 parts per million, according to a 2014

study, risks a complete loss of equatorial coral reefs by 2050 to

2100. Between bleaching and acidification, there’s no way out for

corals so long as fossil fuel burning continues. Image source: Threat

to Coral Reefs From Ocean Acidification.)

The

only hope for stopping this ever-expanding harm is a rapid cessation

of fossil fuel emissions. And we owe it to the corals of the world,

the millions of species that depend on them, and the hundreds of

millions of people whose food sources and economic well being come

from the corals.

“And

Then We Wept”

When

researchers told students of the extent of harm to corals upon the

Great Barrier Reef,the

students were reported to have wept.

And with good reason. For our Earth had just experienced a profound

death of beauty. A death of a vital and wondrous living treasure of

our world. A priceless liquid gem of our Earth. A wonder that gives

life to millions of species and one that grants both food and

vitality to Australia herself. For if the reef goes, so does a huge

portion of the living wealth of that Nation and our world.

Sadly,

the tears will just keep coming and coming as these kinds of events

are bound to worsen without the most dramatic and urgent global

actions. The current and most recent catastrophe is thus yet one more

in a litany of wake up calls to the world. But will we hear it loud

and clear enough to act in ways that are necessary to ensure the

corals survival? And what of the billions of creatures and of the

millions of humans too that depend on the corals? Do we care about

them enough to act?

Links:

Hat

tip to Caroline

Hat

tip to Spike

Hat

tip to Colorado Bob

Hat

tip to Ryan in New England

Hat

tip to Griffon

(Please

support public, non-special interest based science like the essential

work that has been provided by Terry Hughes over so many years and

decades. Scientists like Terry provide a vital public service. For

years, they have given us a clear warning of a very real and ever

more present danger. A warning that gives us a fleeting opportunity

to respond to events before we lose the richest living treasures of

our world. Before we are bereft of our ability to continue to make

livelihoods as environmental abundance and the related regional and

global life support systems are irreparably damaged.)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.